I have forgotten what I was searching for on the Internet Archive last week, but somehow I ended up looking at yearbooks of the turn-of-the-century graduating classes of the Salem Normal School, the founding institution of the university where I now teach, Salem State University. The cover of the 1904 yearbook, entitled The New Mosaic, first caught my attention, then the fanciful illustrations inside, and lastly, the writing. I moved on to the 1905 and 1906 yearbooks, titled The New Mosaic and The Mosaic respectively, which were equally charming, and all the way up to 1914, when the yearbook was published with the rather odd title of Normalities (I get it–Normal School/Normalities, but still). It seems that for a brief time, generally the first decade of the twentieth century, the Salem Normal School seniors published really interesting accounts of their educational experiences—focused on what they learned and what was going on in their world rather than simply who they were. After 1915 or so, the yearbooks became Year Books, with the standard “facebook” format still used today: registries of students rather than their own reflections.

These yearbooks are fascinating and rather poignant—they made me miss my own students! The seniors pay tribute to their teachers, to each other, and to the class behind them. We read all about their activities and clubs and how long it took them to walk down Lafayette Street from the train station. There are lots of whimsical drawings—which will be replaced by more straightforward photographs later. I’m including this post under my #salemsuffragesaturday banner as nearly all the students at the Salem Normal School were women in these days, and the editorial staff of these successive yearbooks were exclusively women. Men were admitted to the school from 1898, but their numbers were extremely low during this first decade of the twentieth century: this makes for some rather amusing class pictures, as we can see from the photograph of the 1906 graduating class below. The same ratio for the 1904 class, as the New Mosaic of that year registers excitement for the upcoming graduation of “We girls and one boy”.

The 1906 graduating class of the Salem Normal School

The 1906 graduating class of the Salem Normal School

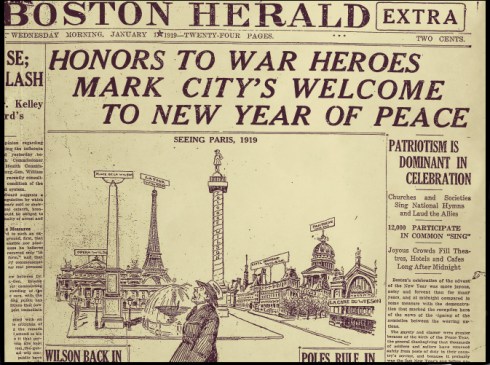

I kept reading because I wanted to see what the students were saying about all the events of the later teens: war, pandemic, suffrage. The yearbooks became less creative, but they started to include editorials: a popular Geography professor who served in World War I died of pneumonia (brought on by influenza?) right after the Armistice and now there were more male students, so the war was very much on the minds of successive editors. Nothing is said about suffrage, which really surprised me: instead there is an overwhelming focus on reforms, developments, and opportunities in the teaching profession. But everything is much more serious than a decade or more before: when the girls, and one or two boys, lived and learned in a much smaller, less-threatening Salem world.

Salem Normal School yearbooks before and after World War I: so many Salem witches in the yearbooks from 1904-8; things get much more serious a decade later: the Liberty Club was dedicated to selling liberty bonds in 1918. The Boston Public Library has a vast collection of yearbooks from nearly every Massachusetts town, most of which have been digitized.

Boston Sunday Post, February 3, 1918 & Boston Sunday Globe, April 7, 1918.

Boston Sunday Post, February 3, 1918 & Boston Sunday Globe, April 7, 1918.

The standard war-time recipe for grape “catchup”, sometimes called catsup and later ketchup: it evolves into a relish over the twentieth century, but earlier in the century there were many different types of catchups: cranberry, mushroom, any fruit or vegetable really, and it was recommended that such sauces be served with roasts. I bet Mrs. Gibney had a more economical recipe for her grape catchup as 2 pounds of sugar would have been very dear in 1918.

The standard war-time recipe for grape “catchup”, sometimes called catsup and later ketchup: it evolves into a relish over the twentieth century, but earlier in the century there were many different types of catchups: cranberry, mushroom, any fruit or vegetable really, and it was recommended that such sauces be served with roasts. I bet Mrs. Gibney had a more economical recipe for her grape catchup as 2 pounds of sugar would have been very dear in 1918. We just discovered that Hamilton Hall served as a Surgical Dressings center for the Salem Red Cross in the summer of 1918, so Mrs. Gibney might have worked there—my attempt at a ghost sign for the Hall!

We just discovered that Hamilton Hall served as a Surgical Dressings center for the Salem Red Cross in the summer of 1918, so Mrs. Gibney might have worked there—my attempt at a ghost sign for the Hall!

Red Cross Nurses assemble masks at Camp Devens, October 1918. National Archives and Records Administration

Red Cross Nurses assemble masks at Camp Devens, October 1918. National Archives and Records Administration

Bradstreet Parker at MIT in the summer of 1918; and in September 24 and 25 Boston Daily Globe articles reporting his death; Ruth Parker (center right) demonstrating her ambulance service training in August of 1918, Boston Daily Globe; the Parker Brothers board game “Chivalry”, 1890s, New York Historical Society Collections.

Bradstreet Parker at MIT in the summer of 1918; and in September 24 and 25 Boston Daily Globe articles reporting his death; Ruth Parker (center right) demonstrating her ambulance service training in August of 1918, Boston Daily Globe; the Parker Brothers board game “Chivalry”, 1890s, New York Historical Society Collections.

French silk New Years’ postcards for 1918 and 1919 featuring the Allied flags, Europeana; Xavier Sager and Santa planting the American flag on the North Pole postcards, 1919, Delcampe.net; Santa’s gift of peace poster by the U.S. Food Administration, Library of Congress; Rudolph Ruzicka holiday card for 1918-1919, Harvard.

French silk New Years’ postcards for 1918 and 1919 featuring the Allied flags, Europeana; Xavier Sager and Santa planting the American flag on the North Pole postcards, 1919, Delcampe.net; Santa’s gift of peace poster by the U.S. Food Administration, Library of Congress; Rudolph Ruzicka holiday card for 1918-1919, Harvard.

Library of Congress & National Museum of American History.

Library of Congress & National Museum of American History.

Historical markers are everywhere in New Hampshire—and Salem’s Massachusetts Tercentenary markers are still among the missing; a Sunday afternoon exhibit/gathering at Hancock’s Historical Society.

Historical markers are everywhere in New Hampshire—and Salem’s Massachusetts Tercentenary markers are still among the missing; a Sunday afternoon exhibit/gathering at Hancock’s Historical Society.

The 101st Field Artillery in France, and just three of Salem’s World War I Memorials.

The 101st Field Artillery in France, and just three of Salem’s World War I Memorials.