(Sorry—I have been reading and writing about meeeting houses for the past few months but still do not know if their identifier is one word or two). On this past Sunday, a rather dreary day, the New Hampshire Preservation Alliance sponsored a driving tour of meeting houses in southern Rockingham County, encompassing structures in Hampstead, Danville, Fremont, and Sandown. I drove over from York Harbor, fighting and defeating an inclination to just stay cozy at home. There was an orientation at Hampstead, the only colonial meeting house of the four that features a steeple addition (I envisioned Salem’s third meeting house, built in 1718), and then we were off to Danville, Fremont and Sandown. I have to tell you, I was in awe all day long: these structures are so well-preserved (cherished, really), simple yet elegant, crafted and composed. I remember thinking to myself when I was first set foot in the Danville meeting house: “I’d rather be here than in Europe’s grandest cathedral” (I think because I had just talked to my brother, on his way to Rome). There’s just something about these places, and the people who care for them. Just to give you a summary of the orientation that I received: they were built in the eighteenth century as both sacred and secular buildings, as close to the center of their settlements as possible and by very professional craftsmen. In the early nineteenth century, their religious and polical functions were seperated, so they became either churches or town halls or were abandoned altogether as other denominations built their own places of worship. It seems to me that they survived because of the preservation inclinations of their surrounding communities, and we were introduced to each meeting house by contemporary stewards who were clearly following in a long line of succession. Nice to encounter historical stewards rather than salesmen.

Hampstead:

The second floor of the meeting house, with its stage and original window frames propped up against the wall and all manner of remnants of civic celebrations, was really charming.

Danville: (which used to be called Hawke, so that’s the name of the meeting house. Hawke, New Hampshire–how cool a name is that!)

Incredible building—I had to catch my breath! I think it has the highest pulpit of these meeting houses, and there was just something about the contrast of that feature and the simplicity (though super-crafted) of the rest of the interior that was striking.

Fremont (which used to be called Poplin):

This meeting house is the only one remaining in NH with “twin porches” on each side, plus a hearse house (see more here–I have long been obsessed and have been to Fremont before but never inside the meeting house or the hearse house) with a horse-drawn hearse inside plus an extant town pound! Very simple inside, but note the sloping second-floor floors in picture #4 above. Took me a while to get used to those.

Sandown:

The most high-style of this set of meeting houses, particularly impressive from the back, I thought. Very light inside, even on this miserable day. Another high pulpit, and more marbleized pillars. Short steps to the second floor–I’m a size 7!

My photos are a bit grainy–not sure what my settings were, I was shifting them around to get more light, and too awestruck by the architecture to really focus, so in compensation I want to refer to you the wonderful work of photographer Paul Wainwright, who has photographed all of these meeting houses and more. Simply stunning!

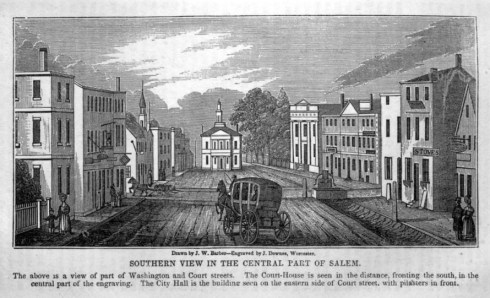

Salem Gazette, July 1796.

Salem Gazette, July 1796. .

.

The Tabernacle Church of 1777-1854, from Samuel Worcester’s Memorial of the Old and New Tabernacle (1855); payments to Daniel Bancroft in the Tabernacle Church administrative

The Tabernacle Church of 1777-1854, from Samuel Worcester’s Memorial of the Old and New Tabernacle (1855); payments to Daniel Bancroft in the Tabernacle Church administrative