Well, October is upon us here in Salem, so that means I’m going to spend all my time inside or on the road. I’m just not a fan of Haunted Happenings, the City’s Halloween festival that starts earlier with each passing year: crowds are converging from at least mid-September now. On September 22, when eight convicted “witches” were hung at Proctor’s Ledge in 1692, you can see people dancing in the streets in Salem. Haunted Happenings is now in its 50th year and this is an anniversary worth celebrating for many, but for me, it’s just fifty years of turning tragedy into treasure. While I do not see or celebrate the connection between the tragedy of the Salem Witch Trials and Halloween, I still find the customs and traditions associated with the latter holiday very interesting, and as I’m teaching my “Magic and Witchcraft in early Modern Europe” course this semester, I find myself subsumed in the source and secondary literature of these complex topics. I haven’t taught this course in 5 years so it definitely needs a refresh! I have learned so much teaching this course over my career at Salem State: at the beginning I offered it simply as a corrective to what I saw (and still see) as a simplistic understanding of witch trials here in Salem, but every time I taught it I learned more about Christian theology and European folklore: after about a decade of teaching it I felt that I needed to undertake more serious study of the former and and contemplated going to Divinity School and now I feel like I need an advanced degree in folklore! It’s all so interwoven, and the focus on both magic and witchcraft over the medieval and early modern eras enables one to see how and why pre-Christian beliefs were assimilated into Christianity—and/or demonized. This coming week we are going to look at some important high and later-medieval herbals and the “magic” that was contained therein, so I decided to make a list of the top ten magical plants. This was a more difficult task than I though it would be as so many plants have protective/proactive virtues associated with them, but this is my list. I’m leaving out Mandrake because we all know that’s the most magical plant of them all, and as many plants were seen to be powerful in both facilitating and dispelling magic I’m going with the most efficacious, by reputation.

Vervain: actually might be more powerful than mandrake. It was known as both an “enchanter’s plant” and an antidote against witchcraft. Gathering vervain seems to have been somewhat of a sacred ritual and there doesn’t seem to be anything that this plant could not do: protect, predict, heal, preserve chasteness and procure love. Snakes are often included in illustrations of vervain: both slithering varieties in the marginalia and more threatening serpents at center stage. Clearly it was percieved as an effective weapon against both.

British Library MSS Sloane 1975 and Egerton 747.

St. John’s Wort: a powerful demon-repellent as you can see by this retreating demon in the fifteenth-century Italian Tractatus de Herbis (British Library Codex Sloane 4016). Referred to as a “devil-chaser” on the Continent, St. John’s Wort was also worn as a protective amulet and used as decoration for doorways and windows on St. John’s Eve at midsummer, when its yellow flowers bloom. Its association with St. John the Baptist also bequeathed it medical virtues, and it was used to staunch bleeding, especially from the thrusts of poisoned weapons, and treat wounds.

British Library Codex Sloane 4016 and MS Egerton 747.

Rue: one of my very favorite herbs, and the sole survivor of my garden of plague cures from twenty years ago! The “herb of grace” was prized for its potency against the plague, infections, and also poison, signalled by its bitterness. It was also believed to be a preserver of eyesight, but it’s best to focus on the general rather than the particulars with this very efficacious herb, which could ward off witchcraft and was used in masses and exorcisms as well as an abortifacient. I just think its gray-green leaves are beautiful, and it adds structure to the garden all season long.

Plantae Utiliores; or Illustrations of useful plants, employed in the Arts and Medicine, M.A.Burnett,1842.

Scabiosa: was far more interesting in the medieval period than its profile as a perfect cottage garden plant now. It was known as “Devil’s Bit” because of the appearance of its root, which looks like someone took a bite out of it. According to John Gerard, who was known to “borrow” information rather indiscriminately, “the great part of the root seems to be bitten away; old fantastic charmers do report that the Devil did bite it for envy, because it is an herb that has so many good virtues, and is so beneficial to mankind.” It was perceived as particularly beneficial to the skin, hence its name, a far cry from “pincushion flower.”

British Library MS Egerton 747; William Catto, 1915, Aberdeen Archives, Gallery & Museums.

Garlic: also has a devilish nickname, the “Devil’s Posy,” and cure-all connotations, so that it was also known as the “Poor Man’s Treacle.” (Treacle is an English sweet now, but in the late medieval and early modern eras it was an anglicization for “theriac,” the universal panacea.) There’s an interesting old tale that when Satan stepped out of the Garden of Eden after his great triumph, garlic sprang from the spot where his left foot lay, and onions from where he had placed his right foot. Like so much folklore, I’m not entirely sure what to do with this information. The key attribute of garlic was its pungent odor: like the bitter taste of rue, this signalled strength: enough to ward off witches, plague, and I guess vampires (though medieval people do not mention the latter).

Garlic (right) and a coiled snake, British Library MS Egerton 747.

Foxglove: a plant with more folkloric pseudonyms than any other! Foxglove: gloves for foxes or fairies or witches? Fairy fingers, ladies’ thimbles, rabbit flowers, throatwort, flapdock, cow-flop, lusmore, lionsmouth, Scotch mercury, dead man’s bells, witches’ gloves, witches’ bells: these are just some of its variant nicknames. Dead man’s bells indicates some knowledge of its potentially poisonous effects, but its cardiac attributes were not known until the eighteenth century. What a tangle with all these names! It’s so interesting to me that a plant can be associated with both witches and the Virgin Mary, as digitalis apparently was. Some of its names also testify to belief in the “doctrine of signatures” by which the appearance of herbs signals their use: foxglove flowers were said to look like an open mouth, and their freckles symbolic of inflamation of the throat: hence, throatwort.

Woodblock trial proof for textiles, 1790-1810, Cooper Hewitt Museum.

Holly: was perceived as very holy, of course. Very little nuance or contradiction with this plant, which Pliny, who seems very accepted by the medievals even though he was a Pagan, credited with the powers to protect and defend against withcraft, lightening, and poison. Its red berries became associated with the blood of Christ over the medieval era, along with its thorny leaves, which made it even more potent. Plant it close to the house, all the traditional authorities say (I feel fortunate that someone did that for my house long ago).

Elizabeth Blackwell’s Curious Herbal, 1737-39.

Moonwort: a little lesser known, but worthy of inclusion if only because it supposedly possesses the ability to open locks and guard silver, as well as unshoe any horses that happen to tread upon it or even near. Ben Jonson referred to it as one of the ingredients of “witches’ broth,” but by his time I think they were throwing everything into that brew. It’s a tiny, tight-fisted, flowering fern (Botrychium lunaria) that just looks like it must have magical qualities, but was also used to heal wounds.

George William Johnson, The British ferns popularly described, and illus. by engravings of every species (1857).

Henbane: is perhaps the most powerful of the bane plants, indicating death by poison, and another plant with both harming and healing virtues, demanding skillful use. It is always mentioned in reference to witchcraft in the late medieval and early modern eras, specifically as an ingredient in ointments (and salves which enabled witches to stick to their brooms!) This might be why it was referred to as the “Devil’s eye” in some regions. But it was also a powerful sedative, known to take away pain, and a hallucinogenic which could take away sense.

Henbane (on the right) in BL MS Egerton 747; Patrick Symons, Still Life with Henbane, 1960, Royal Academy.

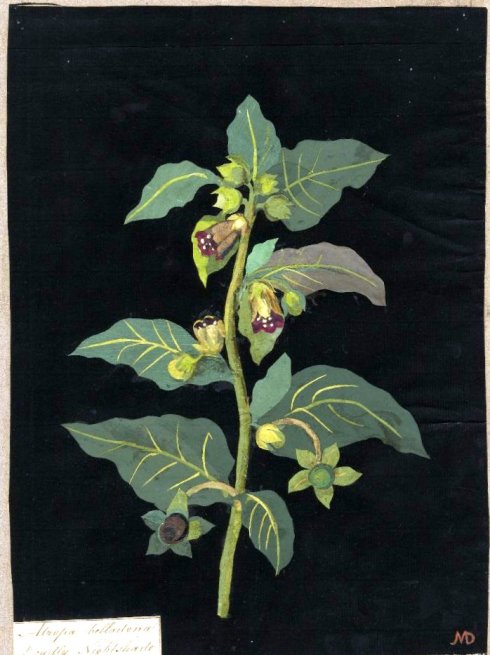

Deadly Nightshade: related to henbane, but even more potent. Every bit of this plant was known to be poisonous, and early modern botanical authors urged their readers to banish it from their gardens. With knowledge and caution, henbane was a plant one could work with, but hands off deadly nightshade! Only the Devil tended it; in fact it was difficult to lure him away from this menacing crop of “devil’s berries” and of course it was yet another ingredient in the strange brews of witches. Its botanical name, Atropa belladonna, indicates its use: The eldest of the Three Fates of classical Greek mythology, the “inflexible” Atropos cut off the thread of life, and the “beautiful ladies” of Renaissance Venice used it in tincture form for wide-open, sparkling eyes. The English adopted the term belladonna in the later sixteenth century, but they also referred to deadly nightshade simply as “dwale,” a stupefying or soporific drink.

William Catto, Aberdeen Archives, Gallery & Museum.

Hanged Men from the Visconti-Sforza deck, c. 1428-50, Cary Collection of Playing Cards, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University and Morgan Library & Museum ; Samuel Y. Edgerton’s CLASSIC book on pittura infamante, with one of Andrea del Sarto’s drawings (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence) on the cover and inside.

Hanged Men from the Visconti-Sforza deck, c. 1428-50, Cary Collection of Playing Cards, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University and Morgan Library & Museum ; Samuel Y. Edgerton’s CLASSIC book on pittura infamante, with one of Andrea del Sarto’s drawings (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence) on the cover and inside.

The Hanged Man in a Flemish Tarot deck from the eighteenth century, and Oscar Wirth’s 1889 deck, British Museum.

The Hanged Man in a Flemish Tarot deck from the eighteenth century, and Oscar Wirth’s 1889 deck, British Museum.