Every year about this time, there is a “it could only happen in Salem” story in the news: this year’s version reports a recent incident of assault and battery by cauldron in a downtown witchcraft shop. Trite but true, and it got me thinking about the association of witches and cauldrons, which I know dates back to the fifteenth century at the very least, and possibly earlier. So I took a little break from my various sabbatical projects and dug in, promising myself that I would devote only one hour to this diversion. It took me away for about 90 minutes, so that’s not too bad. Of course what immediately comes to mind, and is quoted in the newspaper article and all of its variants, is Shakespeare’s quote from Macbeth: Double, double toil and trouble; Fire burn and cauldron bubble. Fillet of a fenny snake, In the cauldron boil and bake. But that’s not the source of the connection; Shakespeare’s words and phrases, clever as they are, are generally a reflection. So what is the connection? I think there are three actually: the Hell-Mouth, the image of the concocting witch as an inversion of the nourishing mother, and poison.

Charles and Mary Lamb, Tales from Shakespeare, 1807

Charles and Mary Lamb, Tales from Shakespeare, 1807

There’s nothing too terribly original about the first two connections; the last, maybe. The Hell-Mouth dates back to the early medieval era, when Hell was first personified as demonic monster who tortures and ultimately devours damned souls: the cauldron-like mouth is both the entrance to Hell and the scene of the torture and devouring, but increasingly in the later medieval manuscripts additional cauldrons (and demons) are added to this horrific depiction. As the cauldron is a tool of Satan, so too is the witch, who also utilizes cauldrons to stir up magical concoctions (with the bodies of unbaptized babies as a primary ingredient) in intensely-anecdotal late medieval texts like Johannes Nider’s Formicarius (1475). By the end of the fifteenth century and the beginning of the sixteenth, we can see these witches, encircling and stirring their cauldrons, in Ulrich Molitor’s De Lamiis et Pythonicis Mulieribus (Of Witches and Diviner Women, 1489) and Hans Baldung’s various witch woodcuts (c. 1510).

Two hundred years of cauldrons: British Library MS Additional 47682, the Harrowing of Hell in the Holkham Bible Picture Book, 1327-35; British Library MS Additional 38128, cauldron-like Hell-Mouth, late 14th-early 15th century; the Prince of Hell with his Cauldron Hat in Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500, Museo del Prado; Molitor’s Weather Witches, 1489; Baldung’s Witches’ Sabbat, c. 1510, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Two hundred years of cauldrons: British Library MS Additional 47682, the Harrowing of Hell in the Holkham Bible Picture Book, 1327-35; British Library MS Additional 38128, cauldron-like Hell-Mouth, late 14th-early 15th century; the Prince of Hell with his Cauldron Hat in Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500, Museo del Prado; Molitor’s Weather Witches, 1489; Baldung’s Witches’ Sabbat, c. 1510, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

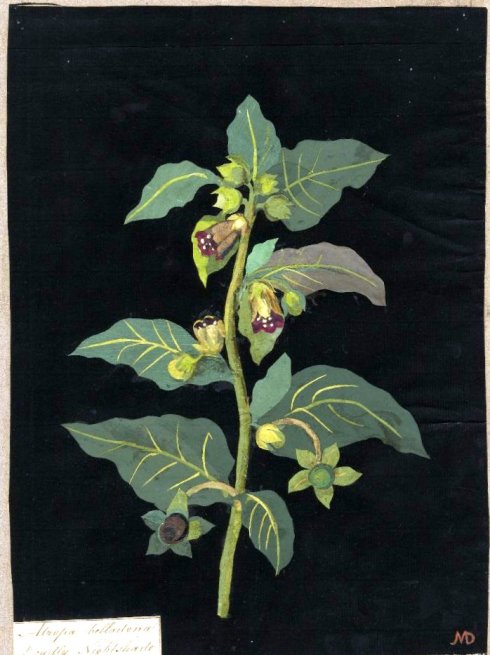

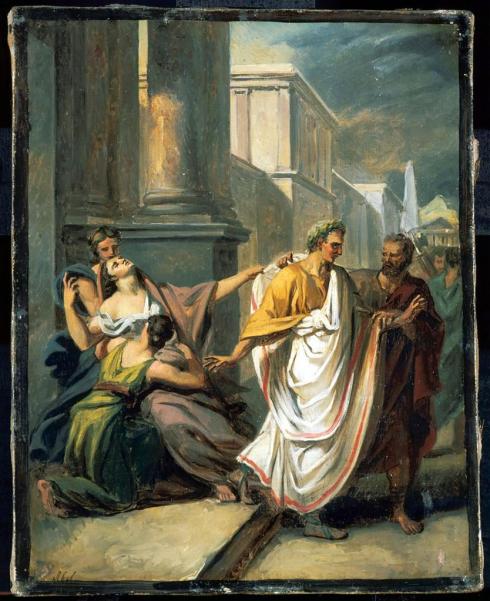

From the sixteenth-century depictions, which will become increasingly lurid into the next century coincidentally with the intense persecution of witchcraft, I think it’s a hop, skip and jump to the folk-tale witches of the nineteenth century and postcard witches of the twentieth from the early twentieth, but there’s one more connection I think is worth exploring, even though I haven’t quite worked it out. A key contributing cause of the early modern witch hunt was the translation of a particular Old Testament passage, Exodus 22:18, into the vernacular as Thou Shall not Suffer a Witch to Live, a translation which Reginald Scot contested in his early and popular skeptical treatise on witchcraft and its prosecution, The Discovery of Witchcraft (1584–one of Shakespeare’s sources). Scot maintained that the original Hebrew word utilized in the passage, which he referred to as Chasaph but is usually referenced (in its root form) as Kasaph, really meant diviner, seer, or poisoner rather than the “witch” of Christian demonology. Before the seventeenth century, the crime of witchcraft in England was perceived more specifically as maleficium, or harmful magic, rather then devil-worship, and poison was the most pernicious form of maleficium: it required knowledge, and skill (and perhaps a cauldron) and those found guilty of bringing about death by poison were sentenced to death by boiling in a cauldron! A sensational poisoning case in 1531 involved Richard Roose, a cook in the household of John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, who attempted to murder his master by poison. The bishop was spared but two people in the household did indeed die before Roose was arrested, tried, convicted and sentenced to death by “boiling” in a cauldron in Smithfield. So much inversion tied to the cauldron and the witch beside it: from nourishment, healing and life to poisoning and death, from childbirth and mother’s milk to infanticide and poisonous gall (referenced by Lady Macbeth) before both are transformed into innocent vessels.

©Historic New England

©Historic New England