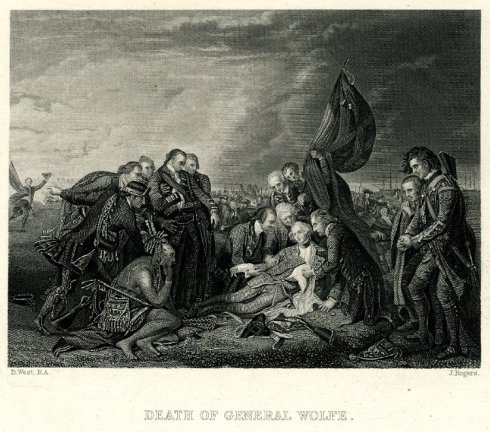

No, not that one, the (three) ones that came years before, which killed Major-General James Wolfe on this day at the decisive Seven Years’ War Battle of Quebec in 1759, a death that was disseminated around the world through the iconic 1770 painting by Benjamin West. The painting and its reproductions, in oil, print, tole, pottery and caricature, became a powerful symbol of the emerging British Empire, even though it was rather ironically the creation of an American-born artist. West broke with tradition by depicting the fallen hero in contemporary uniform rather than classical dress, thus intensifying the identification of his contemporaries, yet still portrayed an eternal, Christ-like figure. The painting was a sensation when it was first exhibited, and for quite a few years thereafter.

Benjamin West, Death of General West, 1770, National Gallery of Canada.

I’m hardly the first historian to pontificate on the importance of this painting: I’m leaning pretty heavily on the analysis of Simon Schama (albeit in “historical novella” form in Dead Certainties: Unwarranted Speculations, 1991) and Linda Colley, more straightforwardly in her magisterial Britons. Forging the Nation, 1707-1837 (1992). Colley calls the painting a “splendid fraud” in that none of the onlookers were even there, most particularly the pensive Native American, who was of course fighting on the other side in what is referred to as the “French and Indian War” over here. Still, Colley observes that “The Death of Wolfe started a vogue for paintings of members of the British officer class defying the world, or directing it, or dying in battle at the moment of victory.” I think this “vogue” was probably due as much to the prints of the painting as the painting itself (most after William Woollett’s engraving), because they were everywhere, in constant circulation up until at least 1820 as far as I can tell: through the American and Napoleonic wars, when Britain needed its heroes. I suppose it was only the cult of Nelson that diminished that of Wolfe, somewhat.

Print made by William Woollett, 1776; Etching for John Young’s ‘A Catalogue of Pictures at Grosvenor House’, 1820; Print by John Rogers , 1830, all Collection of the British Museum; Tole Tray, Northeast Auctions; Creamware Jugs, Christies Auctions; and The Death of the Great Wolf, a satire on the passing of the Treason and Sedition Bills, in 1795, James Gillray, British Museum.