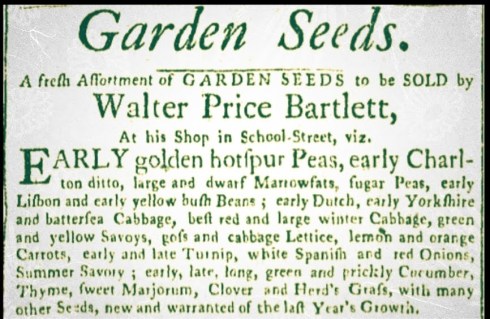

For the most part, this blog has been an academic release for me rather than academic engagement: I consider most of the history I’ve offered up here more pop-up than professional. But there is one academic field with which I have been engaging (mostly in the form of learning) continuously: the history of tourism. This is a relatively new field, emerging in the 1990s, but also a very interdisciplinary and important one, involving social, cultural, and economic factors interacting at local, regional, and global levels. There’s a Journal of Tourism History, several academic book series, and an emerging taxonomy: the general category of Heritage Tourism, for example, can be broken down into more specialized endeavors: literary tourism, thanatourism (also called Dark Tourism, focused on visitation to sites of death and suffering), legacy (genealogical) tourism. Salem became a tourist designation in the later nineteenth century, and from that time its projections have included all of these pursuits. With the bicentennial of the Salem Witch Trials in 1892, witches started appearing everywhere, but Nathaniel Hawthorne represented stiff competition in the opening decades of the twentieth century, particularly after the centennial commemoration of his birth in 1904 and the opening of the House of the Seven Gables in 1910. Over the twentieth century Hawthorne waned and the witches ultimately triumphed, but at mid-century there was a relatively brief span when Salem and its history were both perceived and presented more broadly, as an essential “historyland” which one must visit in order to understand the foundations of American civilization. The major periodicals of the 1940s and 1950s, including Time, Life, American Heritage and National Geographic, presented Salem not only as a Puritan settlement, but also as an “incubator” of both democracy and capitalism with the events of 1692 subsumed by those larger themes.

I think I need to explain and qualify my use of the term “historyland” before I continue, as I’m not using it in the perjorative way that it has come to be used in recent decades: idealized history theme park where one can escape the present and have fun! The “American Way of History” in the words of David Lowenthal. Its meaning evolves, but I am using it first (more later) as it was initially applied: to a region in which much happened and much remained as material legacy to what happened. It emerges in the 1930s as a very specific reference to the area encompassing Jamestown and Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia: I believe a section of Virginia’s Route 3 is still called the “Historyland Highway.” Virginia was so great at marketing itself as Historyland (an example is upper left in the above graphic—some chutzpah to claim that the “nation was preserved” in Virginia!) that other states, like nearby Maryland and North Carolina, started using the term as well. I’m sure that every state on the eastern seaboard was jealous, and the term was extended geographically, chronologically, and conceptually when a Historyland living history park focused on the logging industry opened in Wisconsin in 1954. In the next decade, National Geographic started using the term more generally in reference to national landmarks, in the succession volumes to its popular Wonderlands guides. I don’t want to romanticize the word or its meaning too much: the history that characterized these historylands was overwhelmingly European, narrative, and a bit too focused on colonial costumes for my taste, but at least it was place-based. I can imagine that the civic authorities would have been just a bit wary about the impact of for-profit attractions peddling a story that was not Salem’s in the 1950s and 1960s, especially with the presence of so many non-profit local history museums like the Essex Institute, the Peabody Museum, Pioneer Village, and the Salem Maritime National Historic Site. Clearly that is not a concern now. In characteristic fashion, National Geographic focused on the site-specific aspects of Salem’s past and present in its September 1945 issue, focused on the Northeast. Its industrial base has created some “drabness,” but “this prosaic, utilitarian present is more than matched by an extraordinarily insistent and romantic past. Salem is literally a treasure house of early American landmarks, relics, articles, and documents of historic interest, all easily accessible and within a small area. The little city is fairly haunted by these still-visible evidences of its illustrious position, first as progenitor of the great Massachusetts Bay Colony, and later as a mistress of the seas. Unlike some larger cities of venerable age, in which population grew apace, it was unnecessary for Salem to tear down and rebuild: thus a larger proportion of memorable objects remains undisturbed.” Wow: a city which retains its treasures, was focused on preservation, and haunted by its still visible-past rather than made-up ghosts! What we have lost.

Photographs of Salem from the September 1945 issue of National Geographic, obove, and from America’s Historylands: Landmarks of Liberty (1962) below: the Witch House, secret staircase at the House of the Seven Gables, and Pioneer Village.

This total package, “treasure house” characterization continued to define Salem’s representation in national periodicals over the next two decades, during which Life, Time, and even Ladies Home Journal came to the city to take it all in: the Custom House and Derby Wharf, the House of the Seven Gables, Pioneer Village, the Essex Institute and the Peabody Museum, the Court House with its pins, the YMCA with its small Alexander Graham Bell display (see above), the recently-restored Witch House, and Chestnut Street. (And everything was open all the time! Peirce-Nichols, Derby, all those houses we can seldom enter today). But change was coming, to they ways and means by which we interpreted the past as well as to Salem. From the late 1960s, the meaning of “historyland” took on a more negative meaning and associated “living history” attractions began to fall out of fashion, a trend that culminated with Disney’s disastrous Virginia pitch in the early 1990s. And then Samantha and her Bewitched crew came to Salem, allegedly showing it the way forward: tell one story rather than many and focus on private profits rather than civic pride. The Salem Witch Museum demonstrated that that path could be very successful, and so everybody else jumped on board: the public sanction of “Haunted Happenings” eventually transformed Salem into a full-time Witch City and undermined those institutions which were trying to tell other, or more complicated stories. Many of Salem’s textual treasures have been transferred to Rowley, but I guess we are compensated by the real pirate’s treasure from the Whydah? In recent years, the city’s tourism agency, Destination Salem, has attempted to broaden its appeal by taking advantage of the popularity of genealogical research/travel with its Ancestry Days (next week: see schedule of events here) but I wonder how far that initiative can go when most of Salem’s genealogical assets are in Rowley. Perhaps no structure represents Salem’s transition into a modern historyland, with all of its current connotations, better than the Peabody Essex Museum’s Ropes Mansion, once merely an “early home on an old street” and now the Hocus Pocus house. If I were a true historian of tourism, I could explain this transition in social, cultural, and economic terms, but I’m not there yet. Nevertheless, Salem is the perfect subject for this dynamic field: we’ve already seen some great studies, and I’m sure we’ll see more.

The Ropes Mansion in the May 16, 1958 issue of Life Magazine, and October 2021.

Like this:

Like Loading...

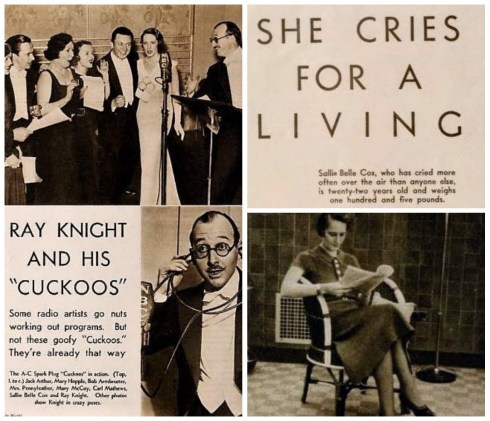

Salem native Raymond Knight and his soon-to-be wife Sallie Belle Cox (behind the microphone at left) in Radio Stars magazine, 1933-34.

Salem native Raymond Knight and his soon-to-be wife Sallie Belle Cox (behind the microphone at left) in Radio Stars magazine, 1933-34.