There are two structures which made an impression on me early in my childhood and sort of set the standard for historic grandeur in my mind: Dartmouth Hall at Dartmouth College, where my father began his career, and The Lady Pepperrell House in Kittery, Maine, close to my hometown of York where we moved when he moved on to the University of New Hampshire. Of course, Dartmouth Hall is a Colonial Revival reproduction of an earlier building, though apparently a very faithful one. I didn’t know that when I stared up at it when I was five or so, and a decade later when I first became concious of the Lady Pepperrell House it evoked that memory. To me, both were New England Georgian exemplars. And yesterday I visited another Georgian exemplar, the Jeremiah Lee Mansion in nearby Marblehead. It was the opening day of its season, and I knew that the charming Rick, one of the most knowledgeable people around about all aspects of local architectural history (just follow his instagram account and you will learn something every day, sometimes every hour) was on docent duty, so I made my reservation and ran over there. It was a cold and gloomy June 1 (especially after a warm Memorial Day weekend), but the house seemed warm and cheerful to me despite its size: this is a grand mansion in every sense of both words.

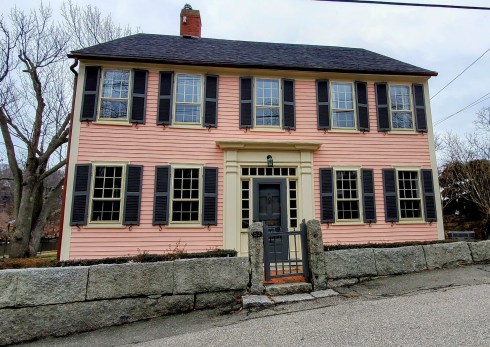

The Mansion is made entirely of wood, but designed to give the appearance of an ashlar stone facade.

The Mansion is made entirely of wood, but designed to give the appearance of an ashlar stone facade.

A bit of history and then I’ll show you some of my interior shots—the gloom outside really highlighted the color inside and I got some great views, if I do say so myself! The mansion was built by 1768 by Colonel Jeremiah Lee (1721-1775), a wealthy “merchant prince” of Marblehead, who was just as engaged in the civic and political life of this bustling maritime community as he was in his brilliant shipping career. Lee was the wealthiest merchant in Massachusetts acccording to tax records from 1771, and he might have been America’s largest pre-revolutionary shipowner with full shares in over twenty vessels. For someone who clearly had so much at stake within the commercial context of the Atlantic world and the British Empire, it’s quite remarkable to see how Lee risked all by becoming a committed Patriot, and even though he did not die in battle, he contracted pneumonia by sleeping in a chilly and wet cornfield on the outskirts of Lexington and Concord on the eve of those battles in April of 1775, certainly a martyr to the cause. So Lee only lived in his trophy house for seven years, and his widow Martha Swett Lee for another decade. We have to dwell in the past a bit longer to understand the sheer scale of this mansion: it seems almost oversized for Old Town Marblehead now, but Marblehead in 1770 was the second largest settlement in Massachusetts, while Salem was the fourth! After the Revolution, Salem commenced its economic and demographic boom, but while the first US census of 1790 reported Salem as the 7th largest city in the new nation (with a population of nearly 8000), Marblehead was still in the pack in 10th place (with a population of 5661). So this mansion represents not only the wealth and cosmopolitan taste of Jeremiah Lee, but also of pre-revolutionary Marblehead. That said, this structure is so very conspicuous and grand, that I understand the words of Miss Hannah Tutt, historian of the Marblead Historical Society, which acquired and restored it after 1909: Fashioned as it was, after the homes of his ancestors, it needed but the hawthorne and the hedgerows to transport one to old England, and indeed the very timbers, of which it was framed, were grown in the mother country. Built at a cost of over ten thousand pounds, it could hardly be rivaled throughout the whole province of Massachusetts Bay—and overshadowing, with its grandeur, the humble home of the fisher folk, no wonder it became to them the “Mansion,” and the “Lee Mansion” it has always been, the pride of the whole town (The Lee Mansion. What it Was and What it is, 1911). Ok, context completed, let’s go inside: first floor first.

Through the front door, you step into this amazing 16-foot-wide entrance hall which extends to the back of house, and it’s all about the central staircase and the handpainted English wallpaper panels, which extend up to the second floor. The house served as the Marblehead Bank for about a century after it left the possession of the Lee family and before it came under the stewardship of the Marblehead Historical Society, so the back and upper stories were closed off. According to Rick, visitors could strip of pieces of this wallpaper as souvenirs in the front part of the first-floor hall, so reproduction paper replaced those parts, but the most of the wallpaper is original and glorious. There is a grain-painted “banquet hall” to the left, and a parlor/drawing room to the right.

Through the front door, you step into this amazing 16-foot-wide entrance hall which extends to the back of house, and it’s all about the central staircase and the handpainted English wallpaper panels, which extend up to the second floor. The house served as the Marblehead Bank for about a century after it left the possession of the Lee family and before it came under the stewardship of the Marblehead Historical Society, so the back and upper stories were closed off. According to Rick, visitors could strip of pieces of this wallpaper as souvenirs in the front part of the first-floor hall, so reproduction paper replaced those parts, but the most of the wallpaper is original and glorious. There is a grain-painted “banquet hall” to the left, and a parlor/drawing room to the right.

There are actually very few items related to Jeremiah Lee in the house; most of the decorative accessories derive from the period but not the family. One feels the presence of Jeremiah and Martha (especially as you pass the copies of their full-length portraits painted by John Singleton Copley on the way to the second floor; the originals are in the Wadsworth Athenaeum), but you feel like you are visiting an eighteenth-century house rather than their house. A very grand eighteenth-century American house. I really appreciated the curation: the Marblehead Historical Society/Museum has been the recipient of a steady succession of decorative donations over the century since it has acquired the Lee Mansion, but the decorative accessories on display were chosen clearly to highlight and complement rather than overwhelm. Nothing competes with the architecture (well, I don’t think anything really could.) On to the second floor.

Second-floor Chambers: the two front rooms are still of considerable size, but things get a bit cozier in the back. The blue-trimmed chamber is a suite of connected small rooms including one with odd proportions and amazing wallpaper! The room with all the yellow damask—a guest room according to Rick—is simply stunning. And you can see that the furniture is top-notch and very complementary.

Second-floor Chambers: the two front rooms are still of considerable size, but things get a bit cozier in the back. The blue-trimmed chamber is a suite of connected small rooms including one with odd proportions and amazing wallpaper! The room with all the yellow damask—a guest room according to Rick—is simply stunning. And you can see that the furniture is top-notch and very complementary.

Beautiful rooms on the second floor, as you can see, but what I am not really showing you is the view. Remember, Marblehead was a busy seaport when this mansion was built: it was not, and is not, a rural estate. Now its grounds are a bit deceptive: there’s a nice side garden but the original lot was quite shallow and a large parcel of land in the back was a later acquisition by the Museum (there is a very interesting article by Narcissa Chamberlain, the wife of photographer Samuel Chamberlain who lived just one street over, about its original boundaries in the April 1969 issue of the Essex Institute Historical Collections). The large windows of the mansion frame the street views out front and the very green views out back, but all I could see was yellow inside, because there is a lot of yellow, but also because I’m working on my new book, a study of saffron, and so I see it everywhere. On to the third floor.

More saffron and more chambers on the third floor: I need these “bed chairs” or whatever you call them! Writing in bed is one of my favorite activities but it takes a toll on one’s back. These third-floor bedchambers were precious. I love this portrait of Miss Selman, the hatboxes, these curvy fancy chairs and settee. Two other rooms on the third floor were a catch-all room with a random collection of museum items (including sea chests with their charts still inside!) and a parlor/playroom/servant’s room in the rear, also filled with wonderful items. I’m not really focusing on the portraits in this post, but there are many interesting ones to see.

More saffron and more chambers on the third floor: I need these “bed chairs” or whatever you call them! Writing in bed is one of my favorite activities but it takes a toll on one’s back. These third-floor bedchambers were precious. I love this portrait of Miss Selman, the hatboxes, these curvy fancy chairs and settee. Two other rooms on the third floor were a catch-all room with a random collection of museum items (including sea chests with their charts still inside!) and a parlor/playroom/servant’s room in the rear, also filled with wonderful items. I’m not really focusing on the portraits in this post, but there are many interesting ones to see.

And down another side staircase (I seem to remember that there are four staircases in the house) to the first-floor kitchen and a small dining/breakfast room where one of Colonel Lee’s logbooks rests on a table and his contemporary Elbridge Gerry looks on. I starting writing as soon as I got home so I wouldn’t forget all the detailed information which Rick imparted to me, but of course everything was just too much to take in so I’m going to have to go back again. I can think of so many sub-stories: the people in the portraits, a Dartmoor Massacre drawing, the wallpapers and printed tiles, those bedchairs, the contributions of my favorite preservationist, Louise du Pont Crowninshield, a summer Marblehead resident. The Marblehead Museum purchased the adjacent property, the site of the Mansion’s brick kitchen and slave quarters, just last year and archeological investigations into the histories of slavery and service in this corner of Marblehead are commencing this very summer. So while there is a lot to see in this majestic mansion, it is not a static site but rather a dynamic one, engaged in an evolving process of discovery and reinterpretation.

The Jeremiah Lee Mansion & Garden: more information and reservations here.

Like this:

Like Loading...

plant propagation in action for those who don’t recognize it—like me!

plant propagation in action for those who don’t recognize it—like me!

Along Concord Street, West Gloucester.

Along Concord Street, West Gloucester.

Along Middle Street, Gloucester.

Along Middle Street, Gloucester.

Eighteenth-century houses in the Lanesville (ORANGE!) and Annisquam villages of Gloucester, and the Edward Harraden House, c. 1660.

Eighteenth-century houses in the Lanesville (ORANGE!) and Annisquam villages of Gloucester, and the Edward Harraden House, c. 1660.

The Mansion is made entirely of wood, but designed to give the appearance of an ashlar stone facade.

The Mansion is made entirely of wood, but designed to give the appearance of an ashlar stone facade.

Through the front door, you step into this amazing 16-foot-wide entrance hall which extends to the back of house, and it’s all about the central staircase and the handpainted English wallpaper panels, which extend up to the second floor. The house served as the Marblehead Bank for about a century after it left the possession of the Lee family and before it came under the stewardship of the Marblehead Historical Society, so the back and upper stories were closed off. According to Rick, visitors could strip of pieces of this wallpaper as souvenirs in the front part of the first-floor hall, so reproduction paper replaced those parts, but the most of the wallpaper is original and glorious. There is a grain-painted “banquet hall” to the left, and a parlor/drawing room to the right.

Through the front door, you step into this amazing 16-foot-wide entrance hall which extends to the back of house, and it’s all about the central staircase and the handpainted English wallpaper panels, which extend up to the second floor. The house served as the Marblehead Bank for about a century after it left the possession of the Lee family and before it came under the stewardship of the Marblehead Historical Society, so the back and upper stories were closed off. According to Rick, visitors could strip of pieces of this wallpaper as souvenirs in the front part of the first-floor hall, so reproduction paper replaced those parts, but the most of the wallpaper is original and glorious. There is a grain-painted “banquet hall” to the left, and a parlor/drawing room to the right.

Second-floor Chambers: the two front rooms are still of considerable size, but things get a bit cozier in the back. The blue-trimmed chamber is a suite of connected small rooms including one with odd proportions and amazing wallpaper! The room with all the yellow damask—a guest room according to Rick—is simply stunning. And you can see that the furniture is top-notch and very complementary.

Second-floor Chambers: the two front rooms are still of considerable size, but things get a bit cozier in the back. The blue-trimmed chamber is a suite of connected small rooms including one with odd proportions and amazing wallpaper! The room with all the yellow damask—a guest room according to Rick—is simply stunning. And you can see that the furniture is top-notch and very complementary.

More saffron and more chambers on the third floor: I need these “bed chairs” or whatever you call them! Writing in bed is one of my favorite activities but it takes a toll on one’s back. These third-floor bedchambers were precious. I love this portrait of Miss Selman, the hatboxes, these curvy fancy chairs and settee. Two other rooms on the third floor were a catch-all room with a random collection of museum items (including sea chests with their charts still inside!) and a parlor/playroom/servant’s room in the rear, also filled with wonderful items. I’m not really focusing on the portraits in this post, but there are many interesting ones to see.

More saffron and more chambers on the third floor: I need these “bed chairs” or whatever you call them! Writing in bed is one of my favorite activities but it takes a toll on one’s back. These third-floor bedchambers were precious. I love this portrait of Miss Selman, the hatboxes, these curvy fancy chairs and settee. Two other rooms on the third floor were a catch-all room with a random collection of museum items (including sea chests with their charts still inside!) and a parlor/playroom/servant’s room in the rear, also filled with wonderful items. I’m not really focusing on the portraits in this post, but there are many interesting ones to see.