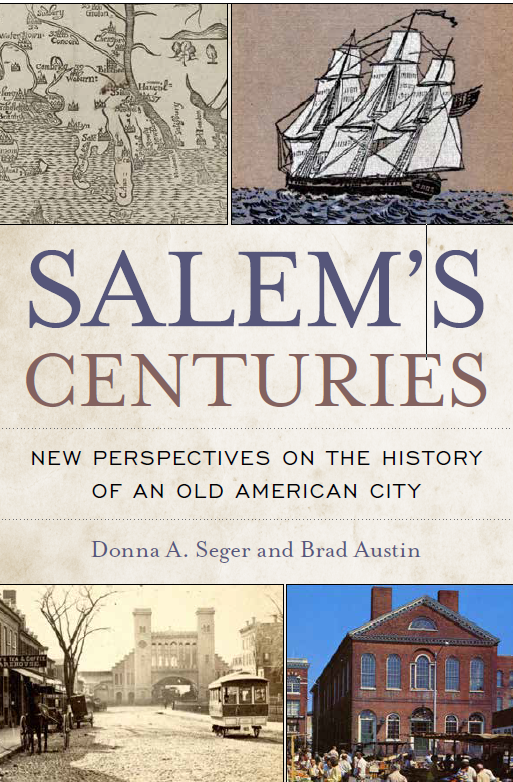

Yesterday I received three copies of Salem’s Centuries. New Perspectives on the History of an Old American City, and Tuesday is publication day, so I thought I’d provide an introductory post. The crucible of this book is definitely this blog, so I want to thank all of its followers, readers, and commenters: I truly am grateful for your support and inspiration! I can’t believe that I’ve been writing in this space for fifteen years: that’s a long time in internet years. It started out as just a vehicle to satisfy my own curiosity about Salem’s history and showcase Salem’s architecture, though I definitely thought I would move on to more worldly topics, despite its title. But the Salem posts were always the most popular, by far (except for anything to do with maps!) And so a more sustained focus on Salem led to the book, but a book is different than a blog. What I share here are mostly stories, but Salem’s Centuries is all about the history of this storied place.

I “posed” the books all over the house!

Salem is indeed a storied place. You (or I) can’t walk down the street without seeing a structure that conjures up some story or inspires the search for one. Stories are part of history, but history is more: layers, context, perspectives. After Covid and the publication of The Practical Renaissance I knew I wanted to write something about Salem for its 400th anniversary in 2026, but I wasn’t sure what—or how. The easiest thing to produce would be a compilation of the Salem stories I have posted here, but I wanted more and I thought Salem deserved more, and so the thought of a proper Salem history emerged. It was an intimidating thought for me, as Salem is an important American city and as I have asserted here time and time again, I am not an American historian. I think I’ve acquired some knowledge and expertise in Salem’s history over these fifteen years, but not enough to sustain a volume that attempts to cover 400 years. So I turned to my colleagues at Salem State, and the result is a collection of essays which explore Salem’s history from different scholarly perspectives across time but centered in place. The key moment in this turn was definitely that in which Brad Austin, our Department chair, 20th century American historian and experienced editor, agreed to be my co-editor. And the rest is history!

Here’s an overview of the book, which will be released everywhere on Tuesday and showcased in a series of events, beginning with a presentation (and hopefully discussion) at Hamilton Hall on January 25. Brad and I are incredibly grateful to the Peabody Essex Museum for centering its PEM Reads podcast on Salem’s Centuries throughout 2026. There’s a lot to discuss, but as both Brad and I realized as we finished this book, there’s also a lot more to learn about Salem’s vast history, so we hope that its reception encourages further research. And that’s exactly where you want to be at the end of a history project: stories end, history doesn’t.

The First Century (note: an innovative feature of our book is its division into full-length chapters and shorter, more focused “interludes” on people, places, and specific events. This was Brad’s idea.):

“Putting Salem on the Maps” is a grand display of historical and geographical context by Brad, and a perfect orientation for our place and book. My colleague Tad Baker has written the definititve history of the Salem Witch Trials, A Storm of Witchcraft, but he is also an archeaologist and historian of the indigenous peoples of New England, and his contributions to our book showcase both these fields of expertise. “The Dispossession of Wenepoykin” gives some much needed historical background of Salem’s “Indian Deed,” and “Gallows Hill’s Long Dark Shadow” is a first-hand account of the revelation of Proctor’s Ledge, a space below Gallows Hill, as the execution site of the victims of 1692, set in historiographical and contemporary contexts. My brief history of Hugh Peter, Salem’s fourth pastor and a regicide of King Charles I, enabled me to indulge in my own scholarly expertise for a bit, and Marilyn Howard’s depiction of John Higginson and his world is a rewrite of one of the best (no, the best) masters’ theses that I have read at Salem State. A magisterial chapter on “Salem and Slavery,” including both indigenous and African-American enslavement in Salem, by my award-winning colleague Bethany Jay, completes this century. Salem’s Centuries contains five pieces on African-American history, all set in larger contexts.

The Second Century:

You would think that an eastern American city as venerable and consequential as Salem would have a published history of its myriad roles during the American Revolution, but no. Hans Schwartz, also a graduate student at Salem State who went on to get his Ph.D. at Clark University, has contributed a succinct yet comprehensive history of these roles in Chapter Four, with an emphasis on the social and economic changes brought about by the Revolution. Another one of our graduate students, Maria Pride, contributes some of her dissertation research on privateering in an interlude on Salem’s “hero among heroes,” Jonathan Haraden, with a little public history push by me. A strong theme of the book is Salem’s continuous “outward entrepreneurialism,” which Dane Morrison’s and Kimberly Alexander’s chapter on the rather tragic expatriate residency of the Kinsman family represents well. “Sabe and Rose” summarizes the collaborative research of Professor Jay and Salem Maritime National Historic Park Education Specialist Maryann Zujewski into the lives of the two people enslaved by Salem’s wealthy Derby family. The much-told story of Mary Spencer, “the Gibralter Woman” who (ironically) made and sold her famous hard candy with slave-made sugar while simultaneoulsy maintaining (and passing down) a fierce Abolitionist stance, gets the Austin treatment while I am able to indulge in a longer history of the man who inspired me to dig in, and dig in deeper, to Salem’s history: patriarch, entrepreneur and abolitonist John Remond.

The Third Century:

The Third Century opens with two studies of Salem and the Civil War by former Salem State graduate students Robert McMicken and Brian Valimont. McMicken contributes a general overview (like the Revolution, there isn’t one!) and Valimont a more focused piece on Captain Luis Emilio of the Massachusetts 54th. Here we have another Salem hero with no statue while a fictional witch reigns in Salem’s most historic square (at least Haraden has a plaque, even though it’s in the Korean barbecue restaurant which stands where his home once did). Our colleague Elizabeth Duclos-Orsello contributes a valuable overview of Salem’s Catholic parishes (Irish, French, Italian and Polish) with her chapter on “Immigrant Catholicisms” and we have another example of Salem’s many connections to Asia in Chapter Nine, “A Salem Scholar Abroad: the Worldview of Walter G. Whitman” by our department’s South Asian historian, Michele Louro, and the Dean of the Salem State Library, Elizabeth McKeigue. This chapter is based on Whitman’s writings and lantern slides of his time in Asia in the SSU Library’s Special Collections, and could definitely be the basis of a larger project. There are two focused studies on Salem Willows in this Century: mine on the evolution of Salem’s famed “Black Picnic” from the eighteenth century to the present, and Brad’s portrayal of the Willows as the “playground” of the North Shore. My chapter on four notable Salem representatives of the Colonial Revival movement definitely transitions well in the twentieth century, while my examination of the 1879 “School Suffrage” election is pretty focused on that one year.

The Fourth Century:

We were slightly deferential to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as Salem historiography has been so focused on the witch trials and maritime history and felt that this last century has been a bit ignored. From a department perspective, we also have several acclaimed twentieth-century historians and wanted to showcase their work. Brad and I worked together on all the editing and introductions in Salem’s Centuries, but the one chapter we co-wrote is an overview Salem’s urban development over the twentieth century, beginning with the aftermath of the Great Salem Fire of 1914. This chapter enabled me to finally figure out Salem’s experience of urban renewal in the 1960s and 1970s! Avi Chomsky, an eminent Latin Americanist who also studies labor history and Hispanic communities here in the US, contributed two pieces to this century, one on the 1933 strike at Salem’s largest employer, the Naumkeag Steam Cotton Company, and another on Salem’s changing demographics in the later twentieth and twenty-first century. Brad worked with SSU archivist Susan Edwards on a chapter on Salem during World War II and with Professor Duclos-Orsello on the Salem State community during the lively 1960s: both pieces are based on SSU archival holdings, which we also wanted to showcase. Readers of this blog have read my rather struggling posts about Salem’s public history in its present “tourism era,” but our book contains two much more illuminating studies by public history professionals Margo Shea and Andrew Darien. Drew Darien, our former chair and now Associate Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at SSU, presents an analysis of oral histories taken during and after a conference held on the occasion of the 325th anniversary of the Witch Trials back in 2017, which Professor Shea and her former graduate student Theresa Giard explore the lure and meaning of one of Salem’s most popular present attractions, ghost tours. Finally, we have an epilogue (by me, exploring or maybe the better word is summarizing 400 years of Salem history through the perspective of one place, Town House Square) and a coda, by our colleague in the English department, J.D. Scrimgeour, Salem’s very first Poet Laureate.

Salem’s Centuries. New Perspectives on the History of an Old American City. Temple University Press, 2026.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Sugar bowl, blue glass, inscribed in gilt with the words ‘East India Sugar / not made by / Slaves’, about 1820-30, probably made in Bristol, England. Museum no.

Sugar bowl, blue glass, inscribed in gilt with the words ‘East India Sugar / not made by / Slaves’, about 1820-30, probably made in Bristol, England. Museum no.