This past Wednesday was my stepson’s 20th birthday and lo and behold, instead of all the outdoorsy things we have done on birthdays past he wanted to go see the collection of armor and arms at the Worcester Art Museum, which absorbed the John Woodman Higgins Armory Collection in 2014. This is the second largest arms and armor collection in the US, and I have been speaking about it to my stepson for a decade or so, so I was thrilled that he wanted to dedicate his birthday to this little trip: Salem is all about the coast and the sea for him in the summer, so going “inland” was quite a change. I hadn’t been to the Worcester Museum for quite some time, but I remembered it as a treasure, and so it remains: it’s just the right size, you don’t get overwhelmed, and you can see a curated timeline of western art from the classical era to the present. Taking their cue from the Renaissance court at its entrance, the galleries are humanistic in their proportions and colors, so the whole experience is rather intimate. We started with the medieval galleries on the first floor, and worked our way to the top: I lingered in the Renaissance rooms, but also really enjoyed those that featured art from Colonial and 19th century America, as it was nice to see some familiar favorites in “person”.

Wednesday at the Worcester Art Museum: the Renaissance Court with These Days of Maiuma by Robert and Shana ParkeHarrison on the wall; Chapter House of the Benedictine priory of St. John Le Bas-Nueil, later 12th century, installed in 1927; armor & weaponry are clustered in the Medieval galleries but spread about in the Renaissance and early modern galleries upstairs; Christ Carrying the Cross, 1401-4, by Taddeo di Bartolo; Vision of Saint Gregory, 1480-90, a FRENCH Renaissance painting; Jan Gossaert, Portrait of Queen Eleanor of Austria, c. 1516 (I was quite taken with this portrait, but the photograph doesn’t really capture it very well–her fur glistened!); Steven van der Meulen, Portrait of John Farnham, 1563. Follower of Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Giovanna Chevara and Giovanni Montalvo, early 1560s.

While Queen Eleanor above was captivating, I am obsessed with the “Madonna of Humility” by Stefano da Verona, a painter with whom I was not familiar. She dates from about 1430, and I think this painting is the essential Renaissance encapsulated: I stared at it for a good half hour, and could have spent hours before/with her.

There was a “Women at WAM” theme running through the galleries, perhaps a holdover from the suffrage centenary last year, and I did find myself focusing on the ladies, both familiar and “new,” from near and far.

Women at WAM: Mrs John Freake and Baby Mary, 1670s; Joseph Badger, Rebecca Orne (of Salem!), 1757; Thomas Gainsborough, Portrait of the Artist’s Daughters, 1760s; Philippe Jacques Van Brée, crop of The Studio of the Flower Painter Van Dael at the Sorbonne, 1816; Att. to John Samuel Blunt or Edward Plummer, An Unidentified Lady Wearing a Green Dress with Jewelry, about 1831; Winslow Homer, The School Mistress, about 1871; Frank Weston Benson (from Salem), Girl Playing Solitaire, 1909.

And then there are those charming “primitives” in the collection, including the very familiar Peaceable Kingdom of Edward Hicks with its odd animals and the Savage family portrait with its odd people! I looked at the latter every which way to try to perfect their proportions, but it’s just not possible.

Edward Hicks’ Peaceable Kingdom, 1833; the big-headed Savage family by Edward Savage, about 1779 (the artist is on the far left–“Savage’s initial struggles with perspective and anatomical proportions are evident in this work”).

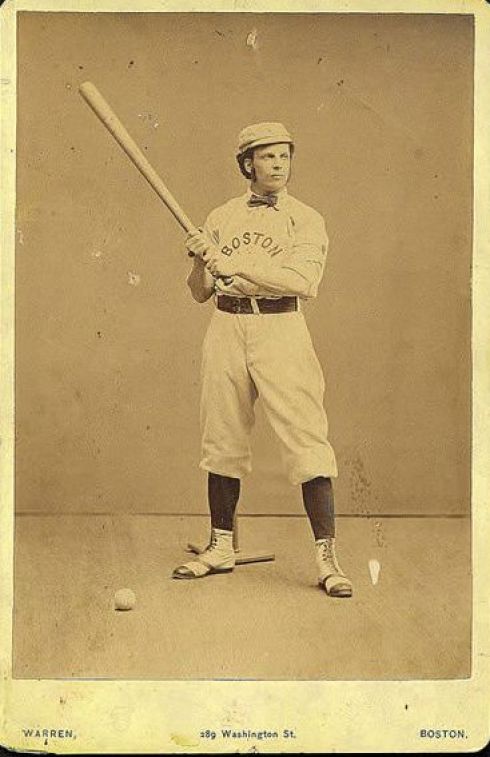

As I said above, the Worcester Art Museum dedicates the majority of its space to its own collections, but there are two very special—and very different—temporary exhibitions on now: one on baseball jerseys, as Worcester is enjoying its first year as home to the Triple A WooSox who have relocated from Pawtucket, and a very poignant display of the processes of theft and retrieval of Austrian collector Richard Neumann’s paintings, the target of Nazi plunder. The story told was fascinating and the pictures presented lovely, but what really caught my attention were their backs, displaying the numbers by which they were added to the “Reichsliste,” the Nazis’ centralized inventory of cultural treasures, and considered for inclusion in Hitler’s Führermuseum. So chilling to see these mundane Nazi numbers.

Baseball jerseys and Nazi numbers at the Worcester Art Museum.

The Base Ball Player’s Pocket Companion. Boston: Mayhew and Baker, 1859.

The Base Ball Player’s Pocket Companion. Boston: Mayhew and Baker, 1859.

All images from Robert Edward

All images from Robert Edward  Baseball Sheet Music

Baseball Sheet Music