I’m starting to work on the proposal for a book on Salem history to be published for the city’s 400th anniversary in 2026. This would be a joint enterprise: I have a colleague (and collegial) co-editor, Brad Austin, and we hope to have contributions from as many members of Salem State’s History Department as possible. Brad came up with the tentative title, Salem’s Centuries: 400 Years of Culture, Conflict, and Contributions, and we already have chapter proposals on topics ranging from the material culture of witchcraft in the seventeenth century to Catholic women in the nineteenth century to initiatives in support of Jewish refugees in the twentieth. As usual, I’m kind of in an odd spot: I’m not an American historian and my academic expertise is winding down just when Salem’s history is beginning! But I do think I have learned some things here, and so I’ve committed to chapters on the Remond family in the nineteenth century and urban development/preservation in the twentieth. I’m going to trust my co-editor and my colleagues who have more authority in these eras to prevent me from embarassing myself! For the Remond chapter, I want to use the family’s hospitality and provisioning roles as avenues into civic life in Salem during the early Republic. I’m fascinated with the idea that John and Nancy Remond, in particular, were catering events for institutions which excluded them. I always thought they were exemplary (and I still do, in many ways), but it turns out that there were actually many African-American caterers working up and down the Atlantic seaboard under similar conditions, pursuing their professional careers in civic settings while at the same time working to advance their civil rights. Despite the identification of African-American caterers in Philadelphia as “as remarkable a trade guild as ever ruled in a medieval city… [who] took complete leadership of the bewildered group of Negroes, and led them steadily to a degree of affluence, culture and respect such as has probably never been surpassed in the history of the Negro in America” by no less than W.E.B. Du Bois in his Negro in Philadelphia: A Social Study (1899), I know very little about these powerful purveyors. This is a perfect exemple of the potential pitfalls I am confronting with this project: I know a lot about the Remonds and their Salem world, but very little about the national context in which they lived and worked.

The Remond menu for the 200th Anniversary of the Settlement of Salem Dinner at Hamilton Hall in September of 1828 (I’m not sure why this was not held in 1826?), Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.

The Remond menu for the 200th Anniversary of the Settlement of Salem Dinner at Hamilton Hall in September of 1828 (I’m not sure why this was not held in 1826?), Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.

Clearly I’ve got to up my game, but this effort will not be a hardship if I get to learn about people like these amazing caterer-abolitionists:

Joshua Bowen Smith (1813-1879): a Pennsylvania native who became a prominent Boston caterer and abolitionist, and later a Massachusetts state senator. Smith catered for Harvard University and many prominent Boston families including that of Robert Gould Shaw, with whom he was reportedly quite close. He was also a close friend of Massachusetts Senator Senator Charles Sumner (along with George T. Downing, below). Smith employed African-American refugees from the South in his business, and aided them in numerous ways through his membership in Boston’s Vigilance Committee, his participation in the Underground Railroad, and his foundation of the New England Freedom Association. Neither his abolitionist activism or his connections aided him when he was stiffed by his fellow abolitionist Governor John Andrew, who refused to pay a $40,000 bill submitted for catering services for the 12th Massachusetts Regiment of Volunteers. Andrew claimed that the legislature had not appropriated the funds, but managed to pay other provisioners without appropriations. Smith was consequently in a financially-vulnerable situation for the rest of his career, but this did not stop his public service.

Joshua Bowen Smith, Massachusetts Historical Society; Bill of Fare for the 75th Anniversary of the American Revolution Dinner for the Boston City Council, 1851. Boston Athenaeum Digital Collections.

Thomas Downing (1791-1866): I think I’ve called John Remond an “oyster king” a few times, and he certainly earned that title in Salem, but his contemporary Thomas Downing was the original Oyster King of a bigger kingdom: New York City. Downing was a native of Chincoteague Island off Virginia (one of my favorite places as a child because of my love for Marguerite Henry’s Misty of Chincoteague: my pony’s name was Chinka), the son of enslaved and then freed parents. He made his way north as a young man, spending some time in that foodie mecca Philadelphia, and then came to New York where his skills as both an oysterman and an entrepreneur enabled him to open the ultimate oyster establishment in 1825. By all accounts, Thomas Downing’s Oyster House was a cut (or several) above all the other oyster “cellars” in New York City, and so it attracted a more genteel, monied, and political crowd. Downing expanded the scale of both his establishment and his business over the next decade, filling mail orders for an international clientele (including Queen Victoria!). Just like John Remond in Salem and Joshua Bowen Smith in Boston, he was also very active in several abolitionist efforts: he founded the Anti-Slavery Society of New York as well as the refuge aid Committee of Thirteen, and worked for both school and transportation desegregation. I’m sure he and John Remond would have heard OF each other, but I’m really curious if they knew each other: they seem to be moving forward on tandem tracks. Downing was definitely the king of PICKLED oysters, which Remond also offered, but I don’t think the New Yorker moved into the latter’s lobster territory.

A stoneware pickled oyster jar from Thomas Downing’s Oyster House (New York City Historical Society) and a handbill for John Remond’s pickled oysters (Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum).

George T. Downing (1813-1903): followed in his father’s footsteps in both his profession and his activism, though primarily in a different setting: Newport, Rhode Island. It’s difficult to discern the difference between a restauranteur and a caterer in this period, but Downing Jr. seems to have operated as both with his establishments in Newport and his role as manager of the Members’ Dining Room at the U.S. House of Representatives in Washington from 1865 to 1877. This position was preceded by a long struggle to desegregate the Newport schools: the Remonds had removed to Newport during their own struggle for school desegregation in Salem in the later 1830s, so I’m pretty certain there is a connection here. Both before and after the Civil War, Downing Jr. was active in all of the abolitionist and equal rights organizations which his father and circle supported, always striving for more equality, more access, and more opportunities for African-Americans.

George Thomas Downing and his family, Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. What I would give for a photograph of all of the Remonds!

Robert Bogle (1774-1848): the first of the emerging Philadelphia African-American “caterers’ guild” referred to by Du Bois above; in fact, Bogle is often credited as not just the first African-American caterer but the first caterer, period (although the term was not used until after his death). He merged the professions of caterer and funeral director in Philadelphia for several decades, inspiring Nicholas Biddle to pay tribute to Boggle in 1830 as one whose “reign extends oe’r nature’s wide domain begins before our earliest breath nor ceases with the hour of death.” Bogle’s Blue Bell Tavern opened in 1813, and soon became famous for its meat pies and terrapin creations as well as a gathering place for Philadelphia’s political leaders: this is the hospitality entrée that accomplished caterers of any color could obtain, but perhaps one of the few avenues of access for African-Americans in the nineteenth century. Indeed, the wonderful digital exhibition on the life and work of an enslaved Charleston cook presented by the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative at the College of Charleston observes that the multi-faceted role of caterer was “one of the few, and most lucrative, prominent public positions that could be acceptably filled by an African American during slavery.”

Nat Fuller (1812-1866): It must have been difficult enough to be an African-American caterer in the North during this period, just imagine what that role would entail in the south! Fortunately we don’t have to imagine because we have this great digital exhibition: Nat Fuller’s Feast: the Life and Legacy of an Enslaved Cook in Charleston. As an enslaved teenager in Charleston in the 1820s, Nat Fuller was apprenticed to a remarkable free African-American couple who seem to be playing the same culinary and catering roles in Charleston that John and Nancy Remond were occupying in Salem, at the exact same time: John and Eliza Seymour Lee. Charleston John was the event manager for several venues; his wife Eliza the famous cook and pastry chef. After Nat Fuller completed his culinary training under Eliza, he worked as an enslaved cook for his slaveholder William C. Gatewood, an ambitious man who entertained frequently, for the next three decades under “evolving” conditions: in 1852 Gatewood agreed to let Fuller live outside of his household with his wife Diana (another famous pastry chef) under the so-called “self-hire” system. The Fullers began to operate independent provisioning and catering businesses in Charleston, paying Gatewood a percentage of their profits. By the later 1850s, though still enslaved, Fuller was Charleston’s “well known” and go-to caterer, staging elaborate events like the Jubilee of Southern Union dinner celebrating the completion of a railway between Memphis and Charleston in May of 1857 for 600 guests. In the fall of 1860, though still enslaved, Fuller opened his famous restaurant, the Bachelor’s Retreat, operating it throughout the war except for a few periods of illness and relocation, and at which, as a newly-free man, he hosted a dinner celebrating the end of the war and slavery in the spring of 1865. Abby Louisa Porcher, a white Charleston lady, documented this momentous event in a letter soon afterwards: “Nat Fuller, a Negro caterer, provided munificently for a miscegenation dinner, at which blacks and whites sat on an equality and gave toasts and sang songs for Lincoln and freedom.” Perhaps Fuller could not operate as a caterer-abolitionist like his colleagues in the North, but he emerged as an advocate for racial equality as soon as he was enabled. He died in the next year.

Appendix: you can read all about the “reenactment” of Nat Fuller’s Feast on the occasion of its 150th anniversary in 2015 here; Invitation below. Another prominent southern African-American caterer, John Dabney of Richmond, was born into slavery, is the subject of a beautiful documentary, The Hail-Storm. John Dabney in Virginia, which you can watch here.

Like this:

Like Loading...

The Remond menu for the 200th Anniversary of the Settlement of Salem Dinner at Hamilton Hall in September of 1828 (I’m not sure why this was not held in 1826?), Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.

The Remond menu for the 200th Anniversary of the Settlement of Salem Dinner at Hamilton Hall in September of 1828 (I’m not sure why this was not held in 1826?), Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.

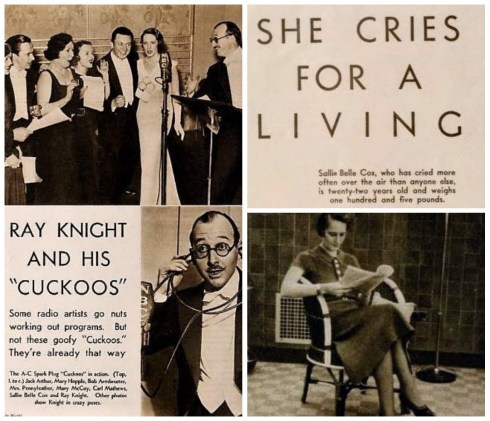

Salem native Raymond Knight and his soon-to-be wife Sallie Belle Cox (behind the microphone at left) in Radio Stars magazine, 1933-34.

Salem native Raymond Knight and his soon-to-be wife Sallie Belle Cox (behind the microphone at left) in Radio Stars magazine, 1933-34.

Distillation is one of the “Accomplished Lady’s” (or her servant’s) responsibilities on the title page of Hannah Woolley’s Accomplished Lady’s Delight, 1684, Folger Shakespeare Library; inset of the frontispiece to The Accomplished Ladies Rich Cabinet of Rarities, 1691, Wellcome Library; Recipe for a classic cordial, Orange Water, in the Folger Shakespeare Library’s MS V.a.669, c. 1680.

Distillation is one of the “Accomplished Lady’s” (or her servant’s) responsibilities on the title page of Hannah Woolley’s Accomplished Lady’s Delight, 1684, Folger Shakespeare Library; inset of the frontispiece to The Accomplished Ladies Rich Cabinet of Rarities, 1691, Wellcome Library; Recipe for a classic cordial, Orange Water, in the Folger Shakespeare Library’s MS V.a.669, c. 1680.

Salem Gazette, 1770,1772,1796.

Salem Gazette, 1770,1772,1796.

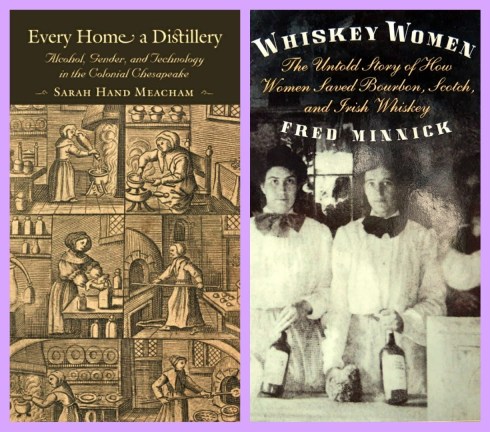

A seventeenth-century stillhouse, and two recent books on distilling women: domestic and commercial.

A seventeenth-century stillhouse, and two recent books on distilling women: domestic and commercial.

John Partridge (with his fancy florets) getting all the credit and a Salem housewife getting none!

John Partridge (with his fancy florets) getting all the credit and a Salem housewife getting none!