I’ve been searching high and low for Salem suffragists, and I have found some, but it’s been a difficult search as there are no extant papers of the “Woman Suffrage Club” of Salem that I can find: newspaper articles, a few flyers, references in diaries and other texts, that’s about it. There are records of many other women’s organizations—charitable groups, religious groups, fellowship groups—which met over different decades of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and among them are the minutes and correspondence of the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society (SFASS), one of the country’s earliest female abolition societies. Looking at all these records, I see familiar names turning up again and again, and as I suspect there were concentric circles of female activism in nineteenth-century Salem, most especially among those women advocating for abolition and suffrage, I am especially grateful that the SFASS archives have been digitized through a partnership of the Congregational and Phillips Libraries. I had a student who worked with these records a year ago for her capstone research and she deemed them “boring”, but I find them fascinating in terms of both content and tone: expressions of a sisterhood of mutual aid and activism pervade even the most administrative of notations.

Records of the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society, 1834-66, Phillips Library MSS 34: available at the Congregational Library. Meeting minutes & Correspondence from William Lloyd Garrison.

Before I get into the activities of the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society, I need to write about Clarissa Lawrence, again. An African-American schoolteacher who lived on High Street in a house that still stands, Lawrence was committed to what was obviously for her an intertwined mission of aid and abolition: she established the first female Anti-Slavery Society in 1832, the Female Anti-Slavery Society of Salem, which consisted solely of free women of color. This organization was folded into the integrated Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1834, but in the interim year, Lawrence also revived and reformed the dormant Colored Female Religious and Moral Society of Salem. This woman was tireless, and relentless, and on fire. She served in the leadership of the SFASS, and was a delegate to the third Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in Philadelphia in May of 1839. On the last day of the convention, Lawrence rose to make a memorable speech, recorded in its proceedings and frequently referenced and reprinted. Yet despite her renown among her peers and historians, she is largely forgotten in the Witch City.

I hope that Mrs. Lawrence felt supported in all of her efforts by her sisters in the newly-formed Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society, all 130 of them, including officers, managers and members. I assume that her election as Vice-President means that she was. The women were very serious about their organization, their meetings, and their minutes. Their first task was to draw up and ratify a constitution, after which they held regular meetings at Mechanic Hall, Creamer Hall, the Masonic Hall, and the Howard Street Church: sub-committee meetings were held at members’ homes. There is one reference to the expenditure of ten dollars for the “privilege of holding our meetings for the enduring year (1837) in the Anti-Slavery Room–occupied by the anti-slavery gentlemen of this city as a reading and debating room”: I have no idea where this might have been, but it conjures up an image of gentlemen reading and debating while the women are doing. Every meeting started with prayers, and decorum was always observed: one young lady who shall remain nameless was asked to resign for her use of “profane” language and she complied. Most of the work of the Society consisted of fundraising in order to support several missions: the purchase of memberships in the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society for those that could not afford them, sending representatives such as Clarissa Lawrence to conventions, supporting “refugees from slavery”, and underwriting William Lloyd Garrison and The Liberator. There were occasional requests for support of vulnerable members of Salem’s free black population—which were answered—but you can tell that the ladies’ primary focus was on those who had escaped from the South. Fundraising primarily took the form of holding fairs, in which the other female anti-slavery societies in the area—in Boston, Marblehead, and Danvers—would contribute, with reciprocation from Salem: the bonds of sisterhood definitely crossed municipal boundaries as well as state lines.

Salem Register, 1841

Salem Register, 1841

Recording Secretary Eliza J. Kenny (sometimes spelled Kenney) was a fascinating woman in several ways, and she will get her own Salem Suffrage Saturday post in the near future: her influence, as well as long-serving President Lucy G. Ives, seems to be behind the lecture series sponsored by the SFASS from 1844-1860, which brought many famous abolitionist advocates to Salem: William Lloyd Garrison seems always ready to speak in Salem, but Wendell Phillips, O.B. Frothingham, William H. Channing and others also came to speak at the Lyceum. The lecture that received the most attention in the press by far was that of “fugitive slave” William Wells Brown, who came to Salem on his first tour as an agent of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, at the beginning of a brilliant career. When asked if he could “represent the real condition of the Slave” Brown replied that he could not: your fastidiousness would not allow me to do it; and if it would, I, for one, should not be willing to do it;—–at least to an audience. Were I to tell you the evils of Slavery, to represent to you the Slave in his lowest degradation, I should wish to take you, one at a time, and whisper it to you. Slavery has never been represented; Slavery never can be represented. What is a Slave? A Slave is one that is in the power of the owner. He is chattel; he is a thing; he is a piece of property. A master can dispose of him, can dispose of his labor, can dispose of his wife, can dispose of his offspring, can dispose of everything that belongs to the Slave, and the Slave shall have no right to speak; he shall have nothing to say. The Slave cannot speak for himself, he cannot speak for his wife, or his children. He is a thing. Brown’s words were by all accounts riveting, so much so that his Salem talk was issued in print, with the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society right there in the title, on the cover, a great example of the Society’s increasing focus on communication in its second and third decades.

Salem Observer, 1847-48; Henry M. Parkhurst’s “phonographic report” of Mr. Brown’s Lyceum Speech.

Salem Observer, 1847-48; Henry M. Parkhurst’s “phonographic report” of Mr. Brown’s Lyceum Speech.

Eliza Kenny led me to the intersection of abolitionism and suffrage: she was the first Salem woman to sponsor a petition, “that the right of suffrage may be extended to women” to the Massachusetts legislature in 1850, right after she attended the first National Women’s Rights Convention in Worcester. I saw lots of familiar names among the 25 women who signed the petition: her anti-slavery sisters. Eliza went down a spiritualist route that made her a less effective (and committed) advocate for either abolition or suffrage later, but her decades of activism are commendable, as are those of the Salem Female Anti-Slavery, which disbanded in 1866, their objective realized at long last. But there were still battles to be waged.

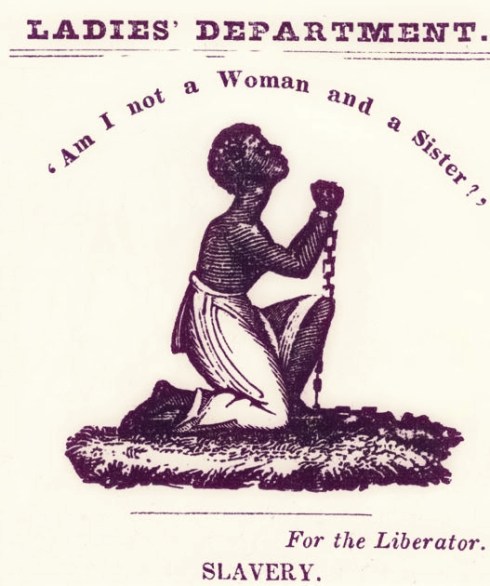

Kenny petition for the Harvard Anti-Slavery Petitions of Massachusetts Dataverse; The Female version of Am I Not A………., first used in George Bourne’s Slavery Illustrated in Its Effects upon Women (1837).