Today’s #SalemSuffrageSaturday post is really more of a list than a composition, and a working list at that: I want to take a stab at identifying as many female Salem artists as I can, although I know it’s an impossible task. It’s impossible because there were so many, and I’m pretty certain I haven’t tracked them all down, but it’s also a difficult task because of the historical impact of gender. In the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, women were taught artistic and creative skills as part of their informal and formal education: some excelled and were clearly artists, even though they—or anyone else—did not identify themselves as such. I think this especially applies to women who worked in the textile arts but to other women as well. In the nineteenth century we see the emergence of (a few) women who can make their living through their artistic talent and skill; this is rarely possible before.

Fidelia Bridges (1834-1923) by Oliver Ingraham Lay, 1872, Smithsonian: Bridges is probably the first and most successful Salem woman artist, though she traveled widely and lived in Connecticut for most of her professional life.

Fidelia Bridges (1834-1923) by Oliver Ingraham Lay, 1872, Smithsonian: Bridges is probably the first and most successful Salem woman artist, though she traveled widely and lived in Connecticut for most of her professional life.

Daughters of old Salem families, Fidelia Bridges, who worked in several mediums and as both an artist and an illustrator, the Williams sisters, Abigail and Mary, who were both artists as well as art dealers, and sculptress Louise Lander, all found themselves in Rome in the mid-19th century for varying periods of time, drawing inspiration and establishing connections. The Misses Williams returned to the family home on Lafayette Street where they created a studio and loaned their works out to several prominent institutions, including the Essex Institute, which featured its very first art exhibition in 1875 featuring many Williams works. Louise Lander (1826-1923) also returned, reluctantly and eventually, to Salem and the family home at 5 Summer Street when she was shunned by the Anglo-American (and quite Salem-dominant) circle in Rome upon charges of some sort of scandalous behavior which she never deigned to answer. She exhibited her “national statue” of Virginia Dare, the first English child to be born in the New World, to raise money for war relief and moved to Washington, D.C. upon the death of her last Salem sister in 1893.

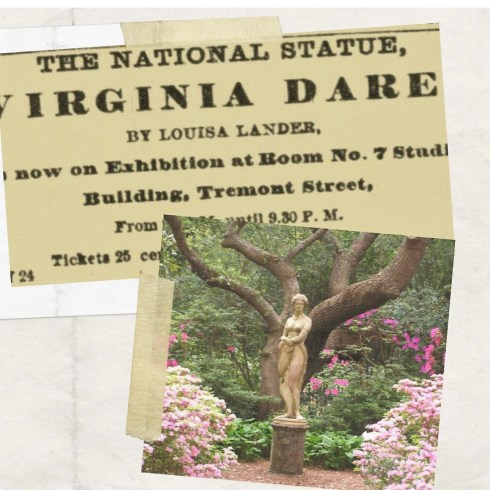

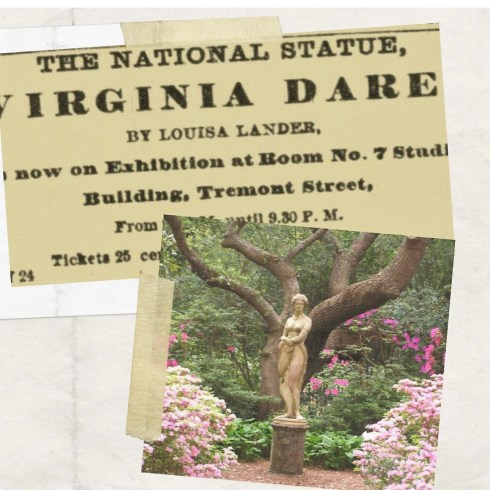

Mary E. Williams, illustrations from The Hours of Raphael in Outline – Together with the Ceiling of the Hall Where They Were Originally Painted (Little, Brown, 1891); Just some of Mary and Abigail Williams’ works shown in the 1875 Essex Institute Exhibition; Virginia Dare in the Elizabethan Gardens & notice in the Boston Post, January 24, 1865.

Mary E. Williams, illustrations from The Hours of Raphael in Outline – Together with the Ceiling of the Hall Where They Were Originally Painted (Little, Brown, 1891); Just some of Mary and Abigail Williams’ works shown in the 1875 Essex Institute Exhibition; Virginia Dare in the Elizabethan Gardens & notice in the Boston Post, January 24, 1865.

To these nineteenth-century artists who seem to be awarded “professional” status I would add Mary Jane Derby (Peabody, 1807-1892) and Mary Mason Brooks (1860-1915) from the generation before and after the “Roman” circle. I’ve written about Derby many times before (see here and here) because I am the fortunate recipient of a journal she composed for her grandchildren, and Brooks more briefly here. Before her marriage, Mary Jane (a cousin of Louisa Lander) was definitely pursuing an artistic career, and she created several lithographs for the Boston firm Pendleton’s Lithography in the 1820s, including a view of her childhood home on Washington Street. Brooks, who worked exclusively in watercolors I believe, was one of the Salem artists who worked out of the famous “studio” at 2 Chestnut Street briefly, and her works were exhibited in Boston and New York. Among Mary Jane’s generation (almost) were two lesser-known artists, Sarah Lockhart Allen (1793-1877), who produced portraits in miniature and pastel, and Hannah Crowninshield( 1789-1834), both of whom were recognized as working artists by their contemporaries. Sophia Peabody Hawthorne (1809-71) is representative of the score of score of female artists who exhibited and sold their works at charitable fairs and bazaars in mid nineteenth-century Salem: always as “misses”.

View of the Nahant House by “MJD” (Mary Jane Derby), Boston Rare Maps; Mary Mason Brooks, The Lumber Schooner, Grogan & Company Auctions. Just a few of the “Fine Arts” exhibitors from Reports of the First Exhibition of the Salem Charitable Mechanic Association : at the Mechanic Hall, in the city of Salem, September, 1849

And then there were all those Salem needlewomen! In her definitive work Girlhood Embroidery: American Samplers and Pictorial Needlework, 1650-1850 (1993), collector and scholar Betty Ring devotes an entire chapter to Salem, focusing on the influential school of Sarah Fiske Stivours (1742-1819) and showcasing the work of Antiss Crowninshield (1726-1768), Love Rawlins Pickman (Frye, 1732-1809), Susannah Saunders (Hopkins, 1754-1838), Betsey Gill (Brooks, 1770-1814), and Mary Richardson (Townsend, 1772-1824) among others. This was a very important Salem art form that was revived in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century by Jenny Brooks, Mary Saltonstall Parker (1856-1920) and other entrepreneurial artists.

Betty Ring’s two-volume Girlhood Embroidery; Salem samplers by Susannah Saunders (Sothebys) and Elizabeth Crowinshield (Doyles); Jenny Brooks Co. advertisements from 1913, and Mary Saltonstall Parker’s cover embroidery for House Beautiful, October 1916.

Betty Ring’s two-volume Girlhood Embroidery; Salem samplers by Susannah Saunders (Sothebys) and Elizabeth Crowinshield (Doyles); Jenny Brooks Co. advertisements from 1913, and Mary Saltonstall Parker’s cover embroidery for House Beautiful, October 1916.

So that brings me to the most entrepreneurial of Salem women artists, or maybe all Salem artists: Sarah Symonds, an artist-craftswoman descended from a long line of Salem craftsmen. I’ve written about Symonds (1870-1965) very recently, so I’m not going to go and on here, but she operated a very successful business selling her cast plaques of historic Salem symbols and structures in the first half of the twentieth century. Following her death in 1965 the Essex Institute, which operated as Salem’s historical society until its amalgamation into the Peabody Essex Museum in 1992, started collecting her works, as they “have enriched our local picture of the past”.

Sarah Symonds in her studio, Phillips MSS 0.202, Papers of Sarah Symonds, 1912-21.

Sarah Symonds in her studio, Phillips MSS 0.202, Papers of Sarah Symonds, 1912-21.

How the past informs the present, and how the present acknowledges, interprets, and builds upon the past are central preoccupations of mine, and artistic perspectives on these processes can be just as illuminating as texts. I’d like to conclude this (again, working) list of women artists from Salem with a contemporary artist whose work is a great example of this illumination: book artist Julie Shaw Lutts. Julie’s a great friend of mine and I’ve featured her work before here, but she has just completed a very timely project which I love, so I wanted to showcase her talents again. The Vote is a mixed media artist’s book which commemorates the achievement of women’s suffrage in ways that are both personal and memorial, material and textual, and touching: all the best ways.

©Julie Shaw Lutts, The Vote.

©Julie Shaw Lutts, The Vote.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Fidelia Bridges (1834-1923) by Oliver Ingraham Lay, 1872, Smithsonian: Bridges is probably the first and most successful Salem woman artist, though she traveled widely and lived in Connecticut for most of her professional life.

Fidelia Bridges (1834-1923) by Oliver Ingraham Lay, 1872, Smithsonian: Bridges is probably the first and most successful Salem woman artist, though she traveled widely and lived in Connecticut for most of her professional life.

Mary E. Williams, illustrations from The Hours of Raphael in Outline – Together with the Ceiling of the Hall Where They Were Originally Painted (Little, Brown, 1891); Just some of Mary and Abigail Williams’ works shown in the 1875 Essex Institute Exhibition; Virginia Dare in the Elizabethan Gardens & notice in the Boston Post, January 24, 1865.

Mary E. Williams, illustrations from The Hours of Raphael in Outline – Together with the Ceiling of the Hall Where They Were Originally Painted (Little, Brown, 1891); Just some of Mary and Abigail Williams’ works shown in the 1875 Essex Institute Exhibition; Virginia Dare in the Elizabethan Gardens & notice in the Boston Post, January 24, 1865.

Betty Ring’s two-volume Girlhood Embroidery; Salem samplers by Susannah Saunders (Sothebys) and Elizabeth Crowinshield (Doyles); Jenny Brooks Co. advertisements from 1913, and Mary Saltonstall Parker’s cover embroidery for House Beautiful, October 1916.

Betty Ring’s two-volume Girlhood Embroidery; Salem samplers by Susannah Saunders (Sothebys) and Elizabeth Crowinshield (Doyles); Jenny Brooks Co. advertisements from 1913, and Mary Saltonstall Parker’s cover embroidery for House Beautiful, October 1916. Sarah Symonds in her studio, Phillips MSS 0.202, Papers of Sarah Symonds, 1912-21.

Sarah Symonds in her studio, Phillips MSS 0.202, Papers of Sarah Symonds, 1912-21.

©Julie Shaw Lutts, The Vote.

©Julie Shaw Lutts, The Vote. Samantha is currently wearing an ensemble by local artist Jacob Belair, which I think is lovely on its own but also because it covers part of her up! I wish it extended to her unfortunate pedestal. I’m not in Salem now, so I asked my stepson ©Allen Seger to take the photos of Samantha in crochet.

Samantha is currently wearing an ensemble by local artist Jacob Belair, which I think is lovely on its own but also because it covers part of her up! I wish it extended to her unfortunate pedestal. I’m not in Salem now, so I asked my stepson ©Allen Seger to take the photos of Samantha in crochet.

The Boston Women’s Memorial by Meredith Bergmann; photographs from her

The Boston Women’s Memorial by Meredith Bergmann; photographs from her

Model and Mock-up of the first and final monument to the Women’s Rights Pioneers by Sculptor Meredith Bergmann, to be unveiled in Central Park on August 26, 2020.

Model and Mock-up of the first and final monument to the Women’s Rights Pioneers by Sculptor Meredith Bergmann, to be unveiled in Central Park on August 26, 2020.

The Knoxville and Nashville Suffrage statues—both by Tennessee sculptor Alan LeQuire—and the unveiling of seven statues of prominent Virginia women last fall: former Virginia First Lady Susan Allen points to a statue of Elizabeth Keckley, dressmaker for Mary Todd Lincoln, and suffragist Adele Clark among the crowds (Bob Brown/ Richmond Times-Dispatch).

The Knoxville and Nashville Suffrage statues—both by Tennessee sculptor Alan LeQuire—and the unveiling of seven statues of prominent Virginia women last fall: former Virginia First Lady Susan Allen points to a statue of Elizabeth Keckley, dressmaker for Mary Todd Lincoln, and suffragist Adele Clark among the crowds (Bob Brown/ Richmond Times-Dispatch).

The Anthony-Stanton-Bloomer statue (1998) by Ted Aub in Seneca Falls; Ira Srole’s “Let’s Have Tea” (2009) in Rochester.

The Anthony-Stanton-Bloomer statue (1998) by Ted Aub in Seneca Falls; Ira Srole’s “Let’s Have Tea” (2009) in Rochester. Office of the Architect of the Capitol.

Office of the Architect of the Capitol.

Advertisements in the Salem Register, 1852 & 1862.

Advertisements in the Salem Register, 1852 & 1862. The Female Medical College

The Female Medical College

Salem Directories, 1882-1892.

Salem Directories, 1882-1892. Ladies Fair for the Poor in Boston, 1858. Boston Public Library

Ladies Fair for the Poor in Boston, 1858. Boston Public Library

Samuel Gridley Howe in the 1850s; Megan Marshall’s great book, although I also like the earlier text on the Peabody sisters: Louise Hall Tharp’s

Samuel Gridley Howe in the 1850s; Megan Marshall’s great book, although I also like the earlier text on the Peabody sisters: Louise Hall Tharp’s

Catalogue of Articles to be Offered for Sale at the Ladies’ Fair at Hamilton Hall in Chestnut Street, Salem, on Wednesday, April 10, 1833 for the Benefit of the New England Asylum for the Blind, National Library of Medicine @National Institute of Health.

Catalogue of Articles to be Offered for Sale at the Ladies’ Fair at Hamilton Hall in Chestnut Street, Salem, on Wednesday, April 10, 1833 for the Benefit of the New England Asylum for the Blind, National Library of Medicine @National Institute of Health.

$3000! in proceeds reported in the Boston Post; Hamilton Hall this morning: still the site of much civic engagement, but unfortunately not today, or for a while……..

$3000! in proceeds reported in the Boston Post; Hamilton Hall this morning: still the site of much civic engagement, but unfortunately not today, or for a while…….. Courtesy Peabody Essex Museum’s Phillips Library.

Courtesy Peabody Essex Museum’s Phillips Library.

Boston Globe headline, December 9, 1879; Library of Congress.

Boston Globe headline, December 9, 1879; Library of Congress.

Ace of Spades card (verso and recto) from a c. 1915 deck published by the National Woman Suffrage Publishing Co., Boston Athenaeum.

Ace of Spades card (verso and recto) from a c. 1915 deck published by the National Woman Suffrage Publishing Co., Boston Athenaeum.

The Mayflower II seemed to be more of a national story in 1957; on the stop in

The Mayflower II seemed to be more of a national story in 1957; on the stop in

The official British program and interactive maps on the Mayflower400 website, which also includes artwork that has been seldom seen (over here, at least), like Anthony Thompson’s 1938 painting The ‘Mayflower’ Leaving Plymouth, 1620 @Essex County Council.

The official British program and interactive maps on the Mayflower400 website, which also includes artwork that has been seldom seen (over here, at least), like Anthony Thompson’s 1938 painting The ‘Mayflower’ Leaving Plymouth, 1620 @Essex County Council.