I wanted to share some examples of the work of the Salem artist George F. White, Jr., better known as George Merwanjee White (1849-1915), but I wish I could also share more details about his life. He’s a bit mysterious, particularly his chosen middle name, Merwanjee, a notable Parsi name. He was the proverbial “son of a Salem ship captain” whose most well-known works are quite local in focus, yet there is evidence that he also traveled widely, in both Europe and India. White’s father, George F. White Sr., made many voyages to the Indian Ocean for shipowners from Salem, Boston, and even New York, so perhaps his son might have accompanied him and was thus exposed to Indian influences, but this is complete conjecture on my part. In any case, by the time White Jr. married at the age of 27 he had shed the “F.” and acquired the “Merwanjee” and that is how he was known throughout his life. George M. White is recognized as part of an “Etching Revival” in Boston and Salem,, a movement which began in the last two decades of the nineteenth century in the latter city, exemplified by the little-known artists Harriet Frances Osborne and White and the more well-known Frank Benson. In addition to his etchings, White produced oil and watercolor paintings and was also recognized as a gifted producer of bookplates, but architectural etchings and drawings seem to be his preferred genre. There is a beautiful portfolio of his images of old Salem houses published by subsciption in 1886 entitled Etchings of Old Houses and Places of Interest in and about Salem which has been digitized for the “Peabody Essex Museum Publications” at the Internet Archive, and below are some of my favorite views. First, the process of production, followed by what was then generally known as the “Roger Williams House” and now the “Witch House,” the Philip English Mansion, the “Old Bakery” on St. Peter Street, later to be moved and renamed the John Ward House at the Essex Institute, the seventeenth-century survivor Narbonne and Pickering Houses, the lost Lewis Hunt and Richard Prince Houses, and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s birthplace in its original location on Union Street.

White’s images are of both old Salem houses—emerging landmarks—which had survived the dynamic nineteenth century (or most of it) as well as fabled houses which had not, thus expressing the beginnings of a preservation conciousness which is also evident in the similar sketches of Edwin Whitefield’s Homes of our Forefathers series, which was published just about the same time. Whitefield is a bit more romantic; White a bit more realistic. White wants to show and tell us what was special about the English, Hunt, and Prince Houses, and he’s wistful about the “picturesque” past: this is a word he applies to both the lost Prince House and the “living” Pickering House, the exterior of which was “fashioned” in the picturesque style of a bygone age in the 1840s. You can’t help but feel that modernity is encroaching.

Heliotype prints from George Merwanjee White’s Etchings of Old Houses and Places of Interest in and about Salem, Limited Edition, 1886.

Two works by Argentinian illustrator

Two works by Argentinian illustrator

Design for a “Mannerist” house with a “catslide” roof in Kent by

Design for a “Mannerist” house with a “catslide” roof in Kent by  Alfred Hitchcock in his Villa Savoye bathroom by

Alfred Hitchcock in his Villa Savoye bathroom by

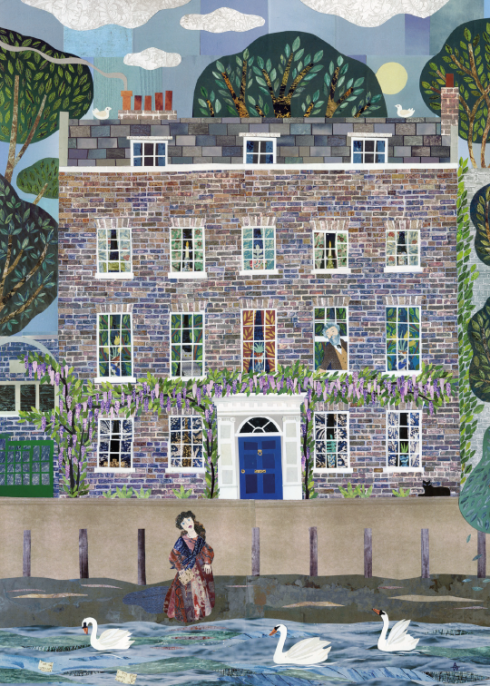

William Morris at Kelmscott House and Dr. Johnson in London,

William Morris at Kelmscott House and Dr. Johnson in London,  Henry VIII at Hampton Court Palace by

Henry VIII at Hampton Court Palace by