Yesterday I learned a new word, drumlin, a long, flat-topped hill formed by glaciers, during my visit to the appropriately-named Long Hill in Beverly, one of the properties of the Trustees of Reservations. At the top of this drumlin, away from the “gold coast” where many of their Boston friends summered, Ellery and Mabel Cabot Sedgwick built a Federal Revival House with bricks harvested from an Ipswich mill and detailed woodwork crafted by enslaved workers from a Charleston mansion. They planted a copper beech tree to mark the spot of their new summer home, and after it was built, kept on clearing and planting, crafting a series of inter-connected gardens around it, designed to frame the home and also blend in with the 100+ acres of woodland and meadows beyond. It’s a spectacular site in so many ways: I’ve visited it many times and posted it about here too, but the Trustees have been engaged in a garden revitalization initiative for their properties, and so I wanted to give Long Hill another look. I took a proper tour rather than just wandering around (highly recommended: it was particularly important for me as I know quite a bit about plants but nothing about trees, and Long Hill has some very unsusual specimens) and now I have a whole new appreciation for this amazing space, and the amazing women who created it.

When Ellery and Mabel Cabot Sedgwick purchased the Long Hill property in 1916, he was in the first phase of his long and successful run as owner and editor of the Atlantic Monthly, which extended to 1938. But she was pretty famous too, having published a popular (and still very useful) gardening guide entitle The Garden Month–By–Month in 1907. The pull-out color chart from The Garden graces Long Hill’s library, framed by silhouettes of Mabel and the second Mrs. Sedgwick, the former Marjorie Russell, who was also an accomplished plantswoman. Together, in succession, they built the spectacular Long Hill gardens, Mabel establishing the integrated “garden rooms” format and Marjorie adding more exotic varieties of plant material—and also focusing on plant propagation and experimentation, often in collaboration with Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum. The property served as the summer retreat for the the entire Sedgwick family, including the four children of Mabel and Ellery and their children, until the death of Marjorie Sedgwick in 1978, after which Theodore Sedwick Bond, Henrietta Sedgwick Lockwood, S. Cabot Sedgwick, and Ellery Sedgwick, Jr. donated Long Hill to the Trustees. It still feels a bit like a family house, even with an event tent on site: accessible rather than stately.

One way the Trustees has enhanced the accessibility of the property is to emphasize the fact that it is a place of activity, still a work in progress as it was under the administration of the two Mrs. Sedgwicks. There’s a cutting garden, a greenhouse and horticultural center, cold frames, ongoing plant propagation, workshops, and for those that don’t want to get their hands dirty, the horticultural library in the house. There are also trails for those who want to explore the rest of the 114-acre property, the “world” beyond cultivation. The overall message is appreciate and act.

plant propagation in action for those who don’t recognize it—like me!

plant propagation in action for those who don’t recognize it—like me!

I’m going to conclude with some of the spectacular trees on the property, just a sampling for sure. I’m just starting to look at trees after a lifetime of being unblissfully unaware, and this is one of the reasons I wanted to revisit Long Hill and will continue to do so. There’s a lot to learn, but yesterday I was just kind of awestruck by some of the textures and colors of the bark, let along the flowers and leaves. It got increasingly humid as we made our way through the garden(s), and so a weeping hemlock was a welcome rest stop, as it was 10 degrees cooling under its dense branches.

These last two amber trees are a Tall Stewartia and a Paperbark Maple.

A few last photos: the house is beautiful, but it’s really just an orientation center for the garden now—-BUT I want you to see this beautiful wallpaper in the center hall, purchased by the Sedgwicks in London during their house furnishing tours in the 1920s, as well an example of “enslaved craftsmanship,” a mantle from the Isaac Ball House in Charleston.

My trillium are finally in bloom about two weeks behind everyone else’s; the lady slippers!

My trillium are finally in bloom about two weeks behind everyone else’s; the lady slippers!

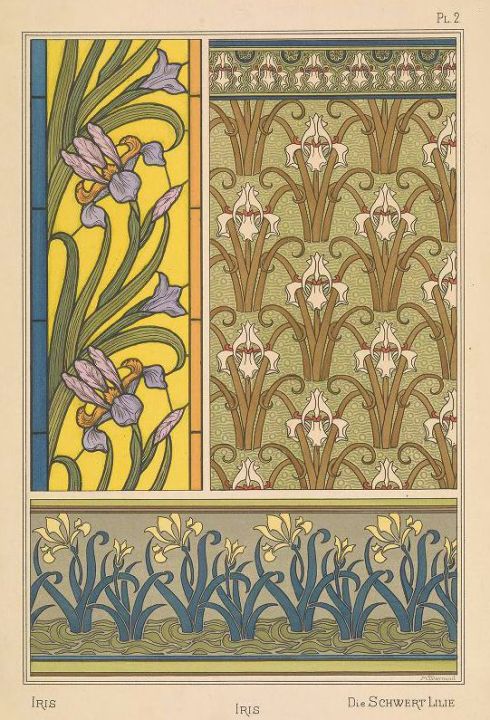

The PEM’s Peirce-Nichols garden has a veritable sea of bleeding hearts, but I was too late for the Solomon’s Seal and Columbine so I give you Grasset.

The PEM’s Peirce-Nichols garden has a veritable sea of bleeding hearts, but I was too late for the Solomon’s Seal and Columbine so I give you Grasset.

Irises and Roses from the PEM’s Ropes Garden, and Grasset’s versions.

Irises and Roses from the PEM’s Ropes Garden, and Grasset’s versions.

Salem’s Fringe trees and Grasset’s dandelion design.

Salem’s Fringe trees and Grasset’s dandelion design.

![20160415_160607_HDR~2[1]](https://i0.wp.com/streetsofsalem.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/20160415_160607_hdr21.jpg?resize=490%2C368&ssl=1)

![20160415_160600_HDR~2[1]](https://i0.wp.com/streetsofsalem.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/20160415_160600_hdr21.jpg?resize=490%2C653&ssl=1)

![20160415_165155_HDR~3[1]](https://i0.wp.com/streetsofsalem.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/20160415_165155_hdr31.jpg?resize=490%2C653&ssl=1)