Sidney Perley (1858-1928) exemplified that exhausting mix of endeavors—historical, genealogical, archaeological, architectural, legal, literary—which in his time was represented by the occupational identity of an “antiquarian.” It was a title he proudly bore, and one which had primarily positive associations a century ago. Now it is itself an antiquated term and I don’t know any historian who would refer to themselves as such. I’ve read pretty much everything Perley wrote about Salem, including the multi-volume History of Salem he published just before he died, and while I wish his work had a bit more context and interpretation, I still value it and think of him as a historian, primarily because he was so very focused on making early public documents public. His meticulous research and publication of probate records, deeds, and town documents was service-oriented; he was very much a public historian in his own time. And more than that: there is a famous dual characterization/division of historians by the French historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, who observed that they fell into one of two camps, either that of truffle hunters, “their noses buried in the details,” or of “parachutists, hanging high in the air and looking for general patterns in the countryside far below them.” Perley was the ultimate truffle hunter, and I’m grateful for all of the detailed information he dug out for me. Because he was trained as a lawyer, Perley’s publications on local history are overwhelmingly based on deed research, and this focus made him somewhat of an architectural historian as well: he sought to portray the built environment, not just land grants and transfers. His wonderful little series of “Parts of Salem in 1700” (and other Essex County towns too), first published in the periodical Essex Antiquarian and/or the Historical Collections of the Essex Institute and later incorporated in the the History of Salem, always included charming illustrations of houses, both on his hand-drawn maps and in the text. Now while I trust Sidney Perley completely in his dates for the construction, transfer, and demolition of these houses, sometimes I think he displays a little artistic license in their depiction. But maybe not: I’m just not sure.

The Essex Antiquarian Volume III (1899).

I’m not sure because sometimes he is a bit vague about the sources for his house illustrations. I would say that I have complete confidence in the depictions of about three-quarters of his illustrations: they were still standing in his time, or had been recently demolished, or had been sketched or photographed before demolition. But with some houses, he is relying on the memory of an anonymous elderly gentleman who gazed at the house early in his life, or on an undated sketch by an anonymous artist found in the depths of the Essex Institute. I’m always interested in the early days of historic preservation, or the first stirrings of some kind of preservation consciousness, so the depictions of these first period houses by Perley and his fellow antiquarians are just fascinating to me: their visions created houses that are still showcased in Salem, most notably the House of the Seven Gables and the Witch (Jonathan Corwin) House. Their visions shaped our visions of the seventeenth century. I like to imagine Perley’s houses still standing, and the best way to do that is to map them: my progress in the acquisition of digital mapping skills stopped as soon as I got my book contract in the summer of 2020, and as I am now working on another book it will stay stalled for a while, but I can cut and paste with the best of them! I am using Jonathan Saunder’s 1820 map of Salem from the Boston Public Library as the background for an evolving Perley map here, but later maps, with more crowded streets, really make these structures stand out too: they must have been so very conspicuous in Perley’s time. I find it interesting that in Europe, very old and very modern structures can coexist, side by side, but we seldom see that in America.

Jonathan P[eele?] Saunders / Engraved by Annin & Smith, Plan of the TOWN OF SALEM IN THE Commonwealth of Massachusetts from actual Surveys made in the years 1796 & 1804; with the improvements and alterations since that period as Surveyed by Jonathan P. Saunders. Boston, 1820. Proceeding clockwise rather haphazardly from the Epes House, on the corner of the present-day Church and Washington Streets, to the Lewis Hunt House, which was photographed before its demolition.

The MacCarter and Bishop Houses: the latter burned down in the 1860s but was fortunately sketched a few years before.

Some survivors in this bunch! The John Day House survived until Frank Cousins could photograph it in the 1890s (Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum), I’m not sure if Perley’s “John Beckett” house on Becket Court is the “Retire Becket” House on the House of the Seven Gables’ campus? Half of the Christopher Babbidge house survives to this day, though it moved to the parking lot of the 20th century building which replaced it.

The “Great Hall” of the PEM Collection Center in Rowley.

The “Great Hall” of the PEM Collection Center in Rowley.

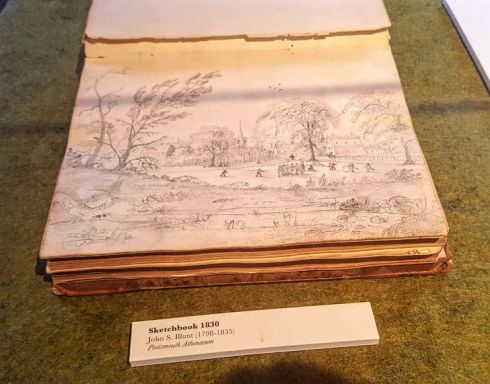

Bookplates and books, newspapers, cyclists, and a working bulletin board at the Portsmouth Athenaeum.

Bookplates and books, newspapers, cyclists, and a working bulletin board at the Portsmouth Athenaeum.

Salem Maritime’s proposed “Derby Wharf Museum” in its 1991 Site Plan, one of several proposed alternatives for the Site which you can see

Salem Maritime’s proposed “Derby Wharf Museum” in its 1991 Site Plan, one of several proposed alternatives for the Site which you can see

New England Magazine, 1892.

New England Magazine, 1892.

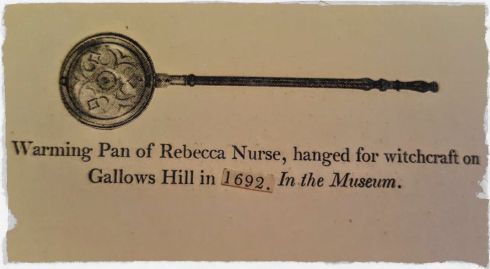

Peabody Essex Museum and Alice Morse Earle, Stage-Coach and Tavern Days (1900).

Peabody Essex Museum and Alice Morse Earle, Stage-Coach and Tavern Days (1900).

The opening page of William Russell’s wartime diary & the warrant for his arrest in December of 1779, Boston Public Library; woodcut broadside illustration of the famous Captain Manley of Marblehead, Peabody Essex Museum.

The opening page of William Russell’s wartime diary & the warrant for his arrest in December of 1779, Boston Public Library; woodcut broadside illustration of the famous Captain Manley of Marblehead, Peabody Essex Museum.

1812

1812

The Bradstreet Tomb today and in its original location in the 1890s (photograph by Frank Cousins @ Digital Commonwealth). Cotton Mather’s epitaph for Bradstreet seems particularly apt: “Here lies New England’s Father! Woe the day! How mingles mightiest dust with meaner clay!”

The Bradstreet Tomb today and in its original location in the 1890s (photograph by Frank Cousins @ Digital Commonwealth). Cotton Mather’s epitaph for Bradstreet seems particularly apt: “Here lies New England’s Father! Woe the day! How mingles mightiest dust with meaner clay!”