For this Veterans Day 2022 the stories of two Salem men named Caleb Foote: grandfather (1750-1787) and grandson (1803-1894). But there’s a shadow of another man in this post too, a young lieutenant named Benjamin West, the sole Salem casualty of the Battle of Bunker Hill. The younger Caleb Foote is the link between the other two men: a prominent newspaper editor and publisher, he also dedicated himself to the remembrance of both his grandfather, a privateer and prisoner of war who left behind quite a revolutionary record, as well as his great uncle, who did not. Their conjoined histories are a great reminder of both the sacrifices made by the first American veterans and the commitments that their descendants made to their memories.

Fortunately members of the Foote family were meticulous writers and archivists of their own family papers. Caleb Foote the Patriot was a wonderful letter writer and journal keeper, both on land and on sea. So we know his Revolutionary story well, and his grandson amplified it by compiling and publishing his records in the Historical Collections of the Essex Institute in 1889. Several of the original texts are preserved among the papers of Divinity Professor Henry Wilder Foote (grandson of Caleb Foote III) at Harvard. According to a letter to his wife Mary, Foote was with General Washington at Cambridge in the fall of 1775, but returned home to Salem after the new year. He then took to the sea as yet another of Salem’s many daring privateers: his vessel, the Massachusetts brigantine Gates, was captured by the British off Canada in July of 1778, after which he was taken to England and imprisoned in Forton Prison near Portsmouth for the next two years. In Spring of 1779, he wrote to Mary back in Salem: I am sorry to inform you that you need not look for me till December or March next altho it may be my good fortune to be at home sooner. Please to remember me to all friends….Capt. Smith, Mr. Hines, Mr. Campton, Mr. Foster, Jacob Tucker, John Shaw, and Jonathan Tarent are in the prison with myself (as Salem served as a major privateer port, so many of its sailors ended up in Forton or Mill Prisons as prisoners of war). Foote grew increasingly exasperated with his imprisonment over his next letters, and with Mary as well, who did not seem to be writing him return letters (oddly he refers to her as “most affectionate friend” in his early letters and “dear beloved wife” in the later ones!) In the summer of 1780 he sounds bereft: my welfare…is very poor at present for here we lie in prison, in a languishing condition and upon very short allowance, surrounded by tyrants, and with no expectation of being redeemed at present, for we seem to be cast out, and forsaken by our country, and no one to grant us any relief in our distress; and many of our noble countrymen are sick and languishing for the want of things to support nature in this low estate of health; and many of they have gave to the shades of darkness. Some others have entered on board His Majesty’s ships to get clothes to cover their nakedness, which is to the shame of America.” This was the low point, after which Foote and several of his fellow prisoners managed to escape and find their way to Amsterdam, where they signed on as crew of the recently-commissioned Privateer South Carolina, which eventually brought them home. Foote kept the log along the way, and was discharged from service in January of 1782, near the end of the Revolution. Five years later he was dead at the age of 37, having never really recovered from his long and difficult service, and leaving Mary and their children in rather desperate straits according to the successive applications for aid sent to various Federal offices on her behalf by august Salem dignitories like Timothy Pickering and Nathaniel Silsbee.

Mary Foote survived her husband by nearly 40 years, during which time she saw her eldest son, namesake Caleb, die at sea, several years after his wife, leaving their sole child, five-year-old Caleb III, an orphan in 1810. His mother belonged to the large West family in Salem, and he was raised by them, chiefly his grandmother, who was the widow of Samuel West, bother of the Benjamin West who was killed at Bunker Hill. The Wests must have discouraged a seaman’s career for young Caleb, because he began an apprenticeship at the Salem Gazette and essentially never left: rising to editor, co-owner, and publisher. He was also a civil servant and the model of nineteenth-century civic engagement, serving as postmaster, school committee member, state representative, and Whig party chairman, as well as on every single infrastructure committee I could find and on the boards of nearly every Salem insitution. He was a temperate Mason. Caleb Foote spoke about his grandfather and namesake at public events regularly, but it wasn’t until towards the end of his life that he began taking up the cause of his great uncle Benjamin, who was for some reason left off the list of names on the Bunker Hill Memorial. Joseph Felt asserted that Benjamin West died “in the trenches” in his 1827 Annals of Salem, but he was unheralded in Boston until the venerable Foote took up his cause in the 1880s, perhaps inspired by his compilation work on his grandfather’s papers. And so we have some charming remembrances, first from Foote himself, who testified that this great-uncle of mine had some taste and talent for portrait painting, and a life-sized bust portrait of him in his lieutenant’s uniform, painted by himself hung in the house [of his grandmother West] , and its history was often mentioned to visitors. A copy of it is now in the possession of the Essex Institute, in Salem, and another in the family…..Another reminiscence was entered into the record that is even more poignant: a column from the late Henry Derby of Salem, whose grandmother was nine years old in 1775 and a neighbor of the Wests. She told her grandson that she remembered that morning of June 17 very clearly, when the young lieutenant came through her mother’s door exhibiting his insignia of office (a feather in his hat) to bid her goodbye. To the question, “Are you going, Benjamin?” “Yes—right away,” was his quick reply and off he went, never to return. Mrs. Derby remembered his artistic skills too. He had a shop downtown with a beautiful and much-admired sign of himself in the process of painting a carriage: a perfect advertisement for his sign-painting business. After his death and the disposal of his effects, this very sign became the lining of an outside cellar door of his family house, his last earthly residence, and there gratified the eyes of children and passers-by whenever these doors were thrown open, till time and exposure erased the picture of this young patriot and martyr to liberty.”

Salem Printer Ezekiel Russell’s Elegiac Poem on the Bloody Battle at Bunker-Hill, Massachusetts Historical Society; West Reminiscences in William Whitmore Story’s A memorial of the American patriots who fell at the Battle of Bunker Hill, June 17, 1775 : with an account of the dedication of memorial tablets on Winthrop Square, Charlestown, June 17, 1889, and an appendix containing illustrative papers (Boston, 1889); Caleb Foote’s 1894 New York Times, obituary, also dated June 17!

A few notes on images: after I read about the self-portrait trade sign on the cellar door above, I spent hours trying to find some semblance. No luck: honestly, the close I could come is Norman Rockwell’s Colonial Sign Painter from 1936! As charming as Norman Rockwell can be, this is not what I was looking for. Much more interesting is the story of the West self-portrait at the Essex Institute, which turns out not to have been a self-portrait, but rather a portrait by his cousin Benjamin Blyth. All this is explained in an article on Benjamin Blyth by Professor Henry Wilder Foote, grandson of Caleb Foote III: what a coincidence! I couldn’t find an image anywhere, which is often the case with portraits which are referenced as deposited with the Essex Institute in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century catalogs and periodicals: I presume it’s up at the Peabody Essex Museum’s storage facility in Rowley. In any case, I love the inscription on the back as noted by Foote: The Gentleman The Patriot The Soldier The Hero.

Norman Rockwell, The New Tavern Sign (Colonial Sign Painter), 1936, Norman Rockwell Museum.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Looking up at the Cliff Walk from York Harbor Beach; the Reading Room is the first building. There used to be four cottages, but they were removed for Hartley Mason Park/Reservation.

Looking up at the Cliff Walk from York Harbor Beach; the Reading Room is the first building. There used to be four cottages, but they were removed for Hartley Mason Park/Reservation.

Must be fully warned! As you will see, some parts of the path are in better shape than others.

Must be fully warned! As you will see, some parts of the path are in better shape than others.

But the path in front of the Reading Room looks great!

But the path in front of the Reading Room looks great! Ok, I get it!

Ok, I get it!

For me, the Cliff Walk was all about private lookouts and houses—it was and is the best way to see some of these cliff-hugging cottages. We always stuck to the path, even when we were mischevious kids.

For me, the Cliff Walk was all about private lookouts and houses—it was and is the best way to see some of these cliff-hugging cottages. We always stuck to the path, even when we were mischevious kids.

Not too great over this stretch.

Not too great over this stretch. My old entrance and exit.

My old entrance and exit.

Nicely-maintained after that but there’s not far to go; that big white house is the home of the hedge-maker and the end of the line.

Nicely-maintained after that but there’s not far to go; that big white house is the home of the hedge-maker and the end of the line. Golden Hour, indeed!

Golden Hour, indeed!

Ace of Spades card (verso and recto) from a c. 1915 deck published by the National Woman Suffrage Publishing Co., Boston Athenaeum.

Ace of Spades card (verso and recto) from a c. 1915 deck published by the National Woman Suffrage Publishing Co., Boston Athenaeum.

The Mayflower II seemed to be more of a national story in 1957; on the stop in

The Mayflower II seemed to be more of a national story in 1957; on the stop in

The official British program and interactive maps on the Mayflower400 website, which also includes artwork that has been seldom seen (over here, at least), like Anthony Thompson’s 1938 painting The ‘Mayflower’ Leaving Plymouth, 1620 @Essex County Council.

The official British program and interactive maps on the Mayflower400 website, which also includes artwork that has been seldom seen (over here, at least), like Anthony Thompson’s 1938 painting The ‘Mayflower’ Leaving Plymouth, 1620 @Essex County Council.

It seems as if Timothy Lindall’s gravestone has always been in the spotlight.

It seems as if Timothy Lindall’s gravestone has always been in the spotlight.

I feel particularly bad for Mr. and Mrs. Nutting, put to rest in a lovely calm neighborhood and now in the midst of the Salem Witch Village! And I really wish that Cousins had photographed my very favorite Charter Street gravestone: that of Mr. Ebenezer Bowditch. What are those carvings? Does anyone know?

I feel particularly bad for Mr. and Mrs. Nutting, put to rest in a lovely calm neighborhood and now in the midst of the Salem Witch Village! And I really wish that Cousins had photographed my very favorite Charter Street gravestone: that of Mr. Ebenezer Bowditch. What are those carvings? Does anyone know?

Old Burying Point Cemetery, Charter Street, Salem, October 2017 & 2018.

Old Burying Point Cemetery, Charter Street, Salem, October 2017 & 2018. The Hearse House in Marlow, New Hampshire.

The Hearse House in Marlow, New Hampshire.

The McDermott Covered Bridge in Langdon (1864); the Meriden Bridge in Plainfield (1880); the Cilleyville (or Bog) Bridge in Andover (1887); the Keniston Bridge, also in Andover (1882); just two of Cornish’s FOUR covered bridges: somehow I missed the “Blow Me Down” Bridge and the Cornish-Windsor Bridge over the Connecticut River is

The McDermott Covered Bridge in Langdon (1864); the Meriden Bridge in Plainfield (1880); the Cilleyville (or Bog) Bridge in Andover (1887); the Keniston Bridge, also in Andover (1882); just two of Cornish’s FOUR covered bridges: somehow I missed the “Blow Me Down” Bridge and the Cornish-Windsor Bridge over the Connecticut River is

Salisbury & Fremont, New Hampshire.

Salisbury & Fremont, New Hampshire. Salem Register, August 19, 1841.

Salem Register, August 19, 1841.

Summer Street from Broad with the Doyle Mansion on the right, Frank Cousins

Summer Street from Broad with the Doyle Mansion on the right, Frank Cousins

Views of the exterior and interior of the Doyle Mansion by Frank Cousins, collection of glass plate negatives at the Phillips Library of the Peabody Essex Museum, Digital Commonwealth.

Views of the exterior and interior of the Doyle Mansion by Frank Cousins, collection of glass plate negatives at the Phillips Library of the Peabody Essex Museum, Digital Commonwealth.

Boston Globe, June 1934; the Holyoke Mutual Fire Insurance building, built in 1936 and now owned by Common Ground Enterprises (and its rather weedy sidewalk!)

Boston Globe, June 1934; the Holyoke Mutual Fire Insurance building, built in 1936 and now owned by Common Ground Enterprises (and its rather weedy sidewalk!)

Pages from Gardner’s Sketchbook, Volume One at Duke University Library’s

Pages from Gardner’s Sketchbook, Volume One at Duke University Library’s

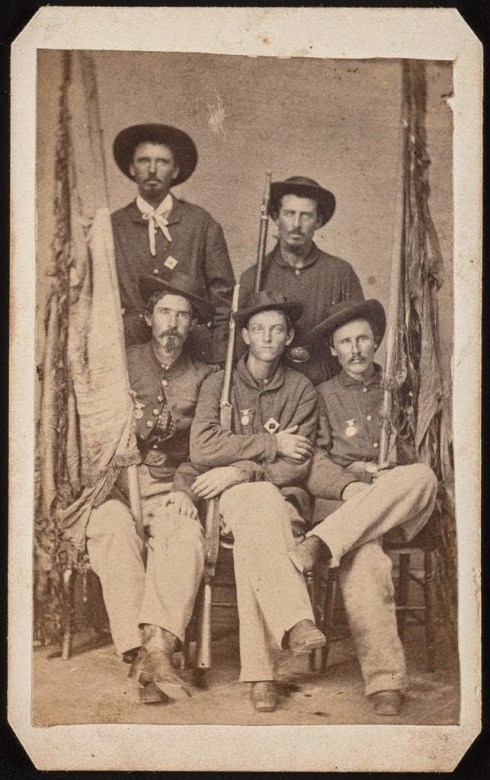

Calvin Townes of the First Regiment; the surviving Regiment at Salem Willows, 1890; Memorials at Spotsylvania and in the Essex Institute, from the History of the First Regiment of Heavy Artillery, Massachusetts Volunteers, formerly the Fourteenth Regiment of Infantry, 1861-1865 (1917); the demolished Harris Farm.

Calvin Townes of the First Regiment; the surviving Regiment at Salem Willows, 1890; Memorials at Spotsylvania and in the Essex Institute, from the History of the First Regiment of Heavy Artillery, Massachusetts Volunteers, formerly the Fourteenth Regiment of Infantry, 1861-1865 (1917); the demolished Harris Farm.

The Munroe House on Lexington Green (which is presently for

The Munroe House on Lexington Green (which is presently for

The Jonathan Corwin (Witch) House, in all of its incarnations in an early 20th century postcard, Historic New England; in 1947 as restored by Gordon Robb and Historic Salem, Inc., and photographed by Harry Sampson, and in the tourist attraction in the 1950s, Arthur Griffin via Digital Commonwealth.

The Jonathan Corwin (Witch) House, in all of its incarnations in an early 20th century postcard, Historic New England; in 1947 as restored by Gordon Robb and Historic Salem, Inc., and photographed by Harry Sampson, and in the tourist attraction in the 1950s, Arthur Griffin via Digital Commonwealth.