I love commemorations: I have posted about them often here, particularly at the beginning of a new year like 2020, during which the long-planned commemorations (of the achievement of women’s suffrage, the Mayflower voyage, and the bicentennial of the state of Maine) didn’t quite go off as planned, obviously. As I spend much of my time thinking about the past, I relish any moment in which a more collective present is so engaged. In four years’ time, Salem is going to be thrust into a big commemorative year, even bigger than 2020 and hopefully more celebratory and reflective: 2026 will mark the 250th Anniversary of the beginning of the American Revolution and the 400th anniversary of the first European settlement in Salem. Revolution 250 has been planning the regional observance of the Revolutionary anniversary for quite some time in a collaborative and dynamic manner, because “commemorations bring people together.” I think there is some Salem participation in this effort, but I’m really not sure. I’m even less sure about what is being planned for Salem’s 400th anniversary: when I look at the organizing that has been going on in two other cities facing big anniversaries, Portsmouth and Gloucester, I see much more organization than is in evidence here in Salem, but then again these cities’ 400th anniversaries are next year so they better have their acts together! Salem certainly has time, but from what foundation and inspiration will it proceed? Who is in charge and who is involved? What will “Salem 400” entail and hope to achieve? I google that term from time to time but all I get is this. Without a professional historical society or heritage commission to shepherd such an initiative, there is no doubt that the 400th anniversary of Salem’s founding will be a much more “top-down” initiative than that of its sister cities, or even its own Tercentenary, which inspired a multi-layered calendar of commemorative events and expressions, including a parade of 10,000 participants, pageants and performances, musters and medals, open houses, bonfires, and headlines in national newspapers.

Official Tercentenary Program, 1926: you can see some great photographs of the events here.

I can’t imagine 10,000 people turning out for a Quadricentennial parade in 2026! The past century has transformed history into a product in Salem, something to be exploited rather than contemplated or celebrated. A singular focus on 1692 seems to have deadened the city’s interest in nearly everything else, save for the occasional nod to the military or the marginalized. I’m not sure how anyone can engage in history in Salem, save for nostalgic facebook postings. The few references to plans and goals for 2026 seem to acknowledge this by emphasizing places over people, and the present over the past: foremost among them is Mayor Kimberley Driscoll’s “Signature Parks Initiative,” which is “focused on planning and carrying out improvements and preservation work in six of Salem’s busiest and most beloved public parks and open spaces, ensuring that they will remain available and enjoyable for future generations to come: Forest River Park, Palmer Cover Park, Pioneer Village, Salem Common, Salem Willows and Winter Island.” Certainly this initiative is welcome, and will be beneficial to Salem’s residents (as will more trees, also a part of “quadricentennial planning”) but is it commemorative? Is it engaging, inspiring, and challenging the public, as opposed to simply providing for them? Maybe it is for some, or even many, but not for me: I want more history—and more humanity—in my quadricentenary. Compare Mayor Driscoll’s Signature Parks Initiative with the centerpiece of the Gloucester 400 commemoration: the 400 Stories Project, “a citywide undertaking whose goal is to collect, preserve, and share 400 stories of Gloucester and its people” from 1623 until 2023. The Project’s administrators invite Gloucester residents to “help us make history” by sharing their stories. This is a pretty sharp commemorative contrast between these two old Essex County settlements.

“Our People, Our Stories”: I wonder what the tagline of Salem’s Quadricentenary will be?

So far the most conspicuous work of the Signature Park Initiative in Salem has been in evidence at Forest River Park in South Salem: one end of the park now features new public pools and trails along with an enlarged and renovated bathhouse while the other is slated for a dramatic alteration revolving around the exchange of the Colonial Revival reproduction “Pioneer Village” currently situated there with the YMCA camp formerly located at Camp Naumkeag in Salem Willows. The writing has been on the wall for Pioneer Village, built for the Massachusetts Tercentenary of 1630, for quite some time as the City has neglected its buildings and landscape for decades and expanded the adjacent baseball field more recently. However, the exchange plan has hit a snag recently, as the City had to apply for a waiver of its own demolition delay ordinance before its own Historical Commission in order to remove the buildings at Camp Naumkeag, which was first established as a tuberculosis camp over a century ago. So far this waiver has not been granted, and a notable resistance to both the destruction of Camp Naumkeag and the relocation of Pioneer Village has emerged. I wrote about Pioneer Village at length last summer, and I have been rather ambivalent up until last month, when several admissions shifted me into the wary and possibly-even-opposed zone: I’m still thinking about it as I find it a particularly vexing public history problem! This is an ambitious plan: Pioneer Village is not simply going to be relocated but rebuilt and re-interpreted with the addition of a visitors’ center and a new focus on the relationship between the European settlers and the indigenous population of pre-Salem Naumkeag. This is an admirable goal for sure, but to my ears, the new interpretive plans sound vague, simplistic and ever-shifting, and above all, lacking in context. They are supposedly the work of the numerous consultants who have worked on the project, paid and unpaid and including several people whom I admire, so it might just be a matter of presentation, but there are several statements that I find concerning. In the first Historical Commission hearing, one consultant responded to the argument that Camp Naumkeag was itself an important historical site because of its role in public health history with an assertion that that role would enhance the new Pioneer Village’s focus on the virgin soil epidemic which devastated the indigenous population even before settlement, as if infectious diseases were interchangeable and detached from time and place! [“Pioneer Village Complicated by History,” Salem News, September 16, 2021] Several months later, the City posted its plans on its website, with this all-encompassing but yet incomprehensible statement of goals: increased access and visibility to the breadth of Salem’s history as represented by the breadth of the site’s history, including Salem Sound’s natural history, the original inhabitants, Fort Lee and the Revolutionary War, the Willows, Camp Naumkeag, and the Pioneer Village. So now it seems as if the newly-situated Pioneer Village will be utilized to interpret almost the entirety, or breadth, of Salem’s history, and in a space which the accompanying plan revealed will have parking for only ten cars. In terms of both interpretation and logistics, this is a flawed plan as presented: its reliance on the seasonal trolley for access is confirmation of its orientation to tourists over residents as well as its seasonal status, in contradiction to the breadth of its stated goals and costs.

The current Plan for the new Pioneer Village on Fort Avenue, on the site of the present-day Camp Naumkeag.

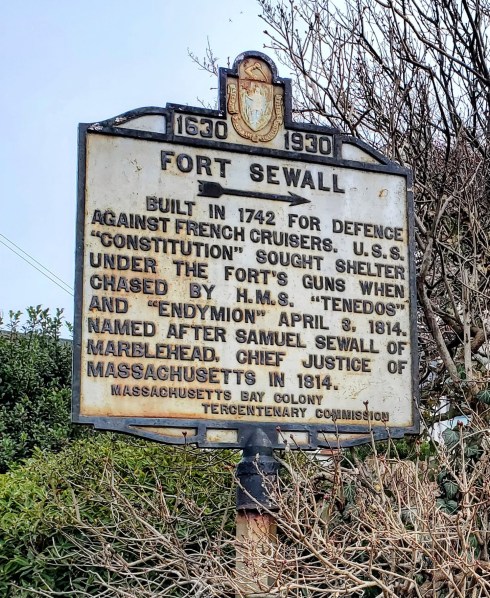

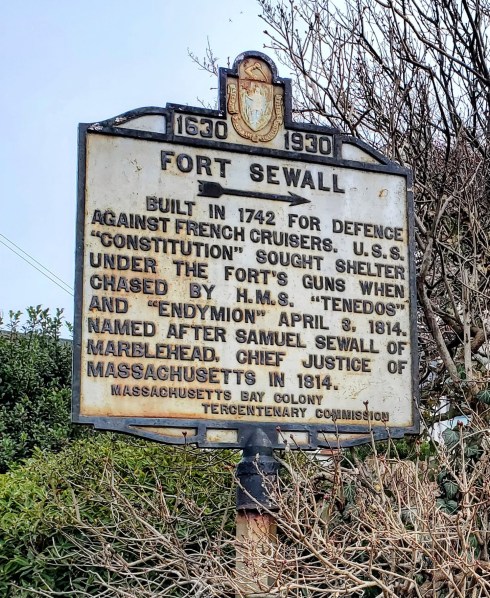

While at face value the inclusion of yet another long-neglected Salem historical resource, Fort Lee, looks like a good thing, I find it concerning. Why should Fort Lee be included in the interpretation of the faux Pioneer Village and not its very authentic (and far more important) neighboring fort on Winter Island, Fort Pickering? This is the guiding principle of the the 2003 study commissioned by the City and the Massachusetts Historic Commission, the Fort Lee and Fort Pickering Conditions Assessment, Cultural Resources Survey, and Maintenance and Restoration Plan: that the forts should be “restored, maintained and interpreted together [emphasis mine] as part of the Salem Neck and Winter Island landscape for enhanced public access.” To its credit, the City has begun a phased rehabilitation of Fort Pickering, but I see much less energy and far fewer resources committed to it than to the Pioneer Village project, which is perplexing given its authenticity and historical importance. Winter Island has served successively as a fishing village, a shipbuilding site, and in continuous military capacities from the very beginning of Salem’s settlement by Europeans to the mid-twentieth century. The storied fortification which became known as Fort Pickering in 1799 was built on the foundation of the British Fort William, part of a massive effort by the new American government to fortify its eastern coastline beginning in 1794 under the direction of French emigré engineer Stephen Rochefontaine. Fort Pickering was manned, and rebuilt, on the occasions of every nineteenth-century conflict, and was especially busy during the Civil War. Another regional Rochefontaine fort, Fort Sewall in Marblehead, shines under the respectful stewardship of that town. Salem is so fortunate to have so much built history: why can’t we focus our energies and resources on preserving and re-engaging with authentic sites, rather than creating new ones? (And could someone please find our SIX Massachusetts Tercentenary markers? Every other town in Massachusetts seems to have held on to theirs).

Talk about a site that can illustrate the BREADTH of Salem history: Winter Island was an early site for fishing and fish flakes (and even more substantial “warehouse” structures) as well as the location of Salem’s first fort William/Pickering. The Salem Frigate Essex (depicted by Joseph Howard) was built adjacent to the Fort in 1799, and Winter Island also served as the site of Salem’s “Execution Hill” in the later eighteenth and nineteenth century and of a Coast Guard air station from 1935-70. Members of the US Coast Guard Women’s Reserve, or SPARS, were stationed on the island during World War II. Rochefontaine’s 1794 plan and block house sketches and Frank Cousins’ photographs of the island and fort in the 1890s, Phillips Library of the Peabody Essex Museum. Marblehead’s Fort Sewall on the last day of December, 2021.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Gloves with Lafayette’s image from the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; a silk bag from the Smithsonian’s Cooper Hewitt Museum, and a ribbon from the collection at Lafayette College.

Gloves with Lafayette’s image from the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; a silk bag from the Smithsonian’s Cooper Hewitt Museum, and a ribbon from the collection at Lafayette College.

Samantha is currently wearing an ensemble by local artist Jacob Belair, which I think is lovely on its own but also because it covers part of her up! I wish it extended to her unfortunate pedestal. I’m not in Salem now, so I asked my stepson ©Allen Seger to take the photos of Samantha in crochet.

Samantha is currently wearing an ensemble by local artist Jacob Belair, which I think is lovely on its own but also because it covers part of her up! I wish it extended to her unfortunate pedestal. I’m not in Salem now, so I asked my stepson ©Allen Seger to take the photos of Samantha in crochet.

The Boston Women’s Memorial by Meredith Bergmann; photographs from her

The Boston Women’s Memorial by Meredith Bergmann; photographs from her

Model and Mock-up of the first and final monument to the Women’s Rights Pioneers by Sculptor Meredith Bergmann, to be unveiled in Central Park on August 26, 2020.

Model and Mock-up of the first and final monument to the Women’s Rights Pioneers by Sculptor Meredith Bergmann, to be unveiled in Central Park on August 26, 2020.

The Knoxville and Nashville Suffrage statues—both by Tennessee sculptor Alan LeQuire—and the unveiling of seven statues of prominent Virginia women last fall: former Virginia First Lady Susan Allen points to a statue of Elizabeth Keckley, dressmaker for Mary Todd Lincoln, and suffragist Adele Clark among the crowds (Bob Brown/ Richmond Times-Dispatch).

The Knoxville and Nashville Suffrage statues—both by Tennessee sculptor Alan LeQuire—and the unveiling of seven statues of prominent Virginia women last fall: former Virginia First Lady Susan Allen points to a statue of Elizabeth Keckley, dressmaker for Mary Todd Lincoln, and suffragist Adele Clark among the crowds (Bob Brown/ Richmond Times-Dispatch).

The Anthony-Stanton-Bloomer statue (1998) by Ted Aub in Seneca Falls; Ira Srole’s “Let’s Have Tea” (2009) in Rochester.

The Anthony-Stanton-Bloomer statue (1998) by Ted Aub in Seneca Falls; Ira Srole’s “Let’s Have Tea” (2009) in Rochester. Office of the Architect of the Capitol.

Office of the Architect of the Capitol.

A coaster’s approach to Boston Harbor and its wharves: John Hills, Boston Harbor and Surroundings, c. 1770-79 & A plan of the town of Boston with the intrenchments &ca. of His Majesty’s forces in 1775 : from the observations of Lieut. Page of His Majesty’s Corps of Engineers, and from those of other gentlemen, Boston Public Library Leventhal Map Center; Essex Gazette, 1771-1774; Salem Gazette, 1796

A coaster’s approach to Boston Harbor and its wharves: John Hills, Boston Harbor and Surroundings, c. 1770-79 & A plan of the town of Boston with the intrenchments &ca. of His Majesty’s forces in 1775 : from the observations of Lieut. Page of His Majesty’s Corps of Engineers, and from those of other gentlemen, Boston Public Library Leventhal Map Center; Essex Gazette, 1771-1774; Salem Gazette, 1796

Boston Herald, May 1904; New York Public Library Digital Gallery.

Boston Herald, May 1904; New York Public Library Digital Gallery.

The emphasis on Hawthorne’s “Homes and Haunts” begins with the Prang publication of William Baxter Palmer Closson’s portfolio in 1886 and continues today! Salem: Place, Myth and Memory was edited by my colleagues at Salem State University and includes a great chapter on Hawthorne by Nancy Lusignan Schultz. I haven’t read Milder’s Hawthorne’s Habitations yet, but it sounds like it is more focused on his time in England and Italy. The Smithsonian photograph above, of the newly-installed statue in front of the newly-built Hawthorne Hotel in 1925, was taken by Salem’s great horticulturist and planner Harlan Kelsey.

The emphasis on Hawthorne’s “Homes and Haunts” begins with the Prang publication of William Baxter Palmer Closson’s portfolio in 1886 and continues today! Salem: Place, Myth and Memory was edited by my colleagues at Salem State University and includes a great chapter on Hawthorne by Nancy Lusignan Schultz. I haven’t read Milder’s Hawthorne’s Habitations yet, but it sounds like it is more focused on his time in England and Italy. The Smithsonian photograph above, of the newly-installed statue in front of the newly-built Hawthorne Hotel in 1925, was taken by Salem’s great horticulturist and planner Harlan Kelsey.

Colonization in America visual wall map, 1966, prepared by the Civic Education Service, Washington, D.C.; David Rumsey Map Collection.

Colonization in America visual wall map, 1966, prepared by the Civic Education Service, Washington, D.C.; David Rumsey Map Collection.

The Jabez Howland

The Jabez Howland

Leyden Street, with the storm coming in.

Leyden Street, with the storm coming in.