I busted out of Salem yesterday and took a road trip to Norfolk county in Massachusetts, southwest of Boston, and drove through a string of towns beginning with M: Medfield, Millis, Medway, Milford, Mendon. My “destination” was a first-period house with Derby connections in the first M town, the Dwight-Derby House, but really I just wanted to drive around. And I did—but I also found Medfield absolutely charming so I stayed awhile. Sometimes I think I could write the whole blog about and around Salem’s Derby family: their money, connections, and influence end up everywhere. In this case, however, neither their money, connections or influenced really impacted the history of a lovely first-period house overlooking Medfield’s Meetinghouse Pond. John Barton Derby, a grandson of Elias Hasket Derby, who profited immensely from Salem’s emerging East India trade and thereby became America’s first millionaire, did not stay in Medfield for long but his descendants lived in what became known as the Dwight–Derby House until the middle of the twentieth century.

John Barton Derby, grandson of Elias Hasket Derby, married Mary Townsend, whose family owned the Medfield house, in 1820. Rumors swirl around about John Barton and his brother Hasket, in contrast to the other children of John and Sarah Derby of Salem. The major clues to their outcast status are the facts that they were seldom in Salem and always in need of money. When John Barton married Mary Townsend, his deceased first wife (from Northampton, which is like Derby Siberia) had not been in her grave for very long, and he was apparently disowned by his father. He was practicing law in Dedham, and had been given a letter of introduction to Mary’s father by his uncle Benjamin Pickman, Jr., but that was about it for respectability. John and Mary remained together for about of 27 months and produced two children, Sarah and George Horatio, and then he was gone. I’m going to let Nehemiah Cleaveland and Alpheus Spring Packard, authors of the History of Bowdoin College with Biographical Sketches of its Graduates, from 1806 to 1879, Inclusive (1882) tell the rest of John’s story, but they are leaving out time spent as a recluse in the wilds of New Hampshire and as a patient at what later became known as McLean Hospital, which opened in the year of John Barton’s graduation from Bowdoin.

“JOHN BARTON DERBY, born in 1793, was the eldest son of John Derby, a Salem merchant. In college he was musical, poetical, and wild. He studied law in Northampton, Mass., and settled as a lawyer in Dedham. His first wife was a Miss Barrell of Northampton. After her death he married a daughter of Horatio Townsend. They soon separated. A son by this marriage, Lieut. George Derby of the United States army, became well known as a humorous writer under the signature of ‘John Phoenix.’ For many years before his death Mr. Derby lived in Boston. At one time he held a subordinate office in the custom-house Then he became a familiar object in State Street, gaining a precarious living by the sale of razors and other small wares. He was now strictly temperate, and having but little else to do, often found amusement and solace in those rhyming habits which he had formed in earlier and brighter years, His Sundays were religiously spent — so at least he told me — in the composition of hymns The sad life which began so gayly came to a close in 1867.” What a poignant scenario: the grandson of a millionaire, with his “precarious living by the sale of razors and other small wares” on the streets of Boston. No wonder the charming sign outside of the Dwight-Derby House features John Barton’s and Mary’s dashing son, George Horatio Derby, who served in the Mexican-American War, went on to a journalistic career in California and died at the young age of 38. You can read much more about the Townsends and the Derbys and the history of the house in a great little book that integrates both very well: Medfield’s Dwight-Derby House. A Story of Love and Persistence by Electa Kane Tritsch.

George Horatio Derby, Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley.

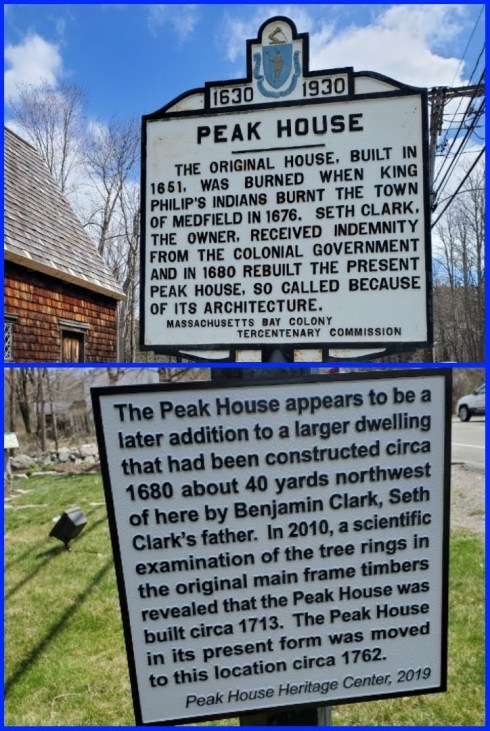

The Dwight-Derby House was purchased by the town of Medfield in 1996, and went through an intensive restoration before it was opened to the public, joining the town’s more famous colonial structure, the Peak House, as a period museum. And there’s lots more in Medfield: some beautiful seventeenth- and eighteenth-century private houses, a small historical society, and a “mobile history tour” using QR code plaques on utility boxes, signs, and murals. I fell in love with the eighteenth-century Clark Tavern, even (or perhaps because of) its state of extravagant decay, and was very relieved to discover that it has just sold and can only be restored to include TWO dwellings (despite being much bigger than the poor Barr house into which many more are being stuffed), or perhaps even to its original use.

I can’t wait to go back to Medfield to see the interior of the Dwight-Derby House, and the renovation of the old Clark Tavern. But there’s lots of history to see and read now at the Peak House (with its revised chronology) and along the town’s streets and sidewalks.

Indian Muslin and silver wedding reception dress of Sarah Ellen Derby Rogers, 1827, Peabody Essex Museum (Gift of Miss Jeannie Dupee, 1979).

Indian Muslin and silver wedding reception dress of Sarah Ellen Derby Rogers, 1827, Peabody Essex Museum (Gift of Miss Jeannie Dupee, 1979).