I have been meaning to post on the most eminent of Salem’s antiquarians, Henry FitzGilbert Waters (1833-1913) for a while, but I kept finding more information about him and thought I’d wait until I had the total picture: but clearly he is one of those people for whom references will always appear and it will be impossible to draw the total picture unless one is doing so in the form of a longer piece or even a book. His papers are at the Phillips Library in Rowley, so that might be an interesting project for someone, as genealogy is so popular right now and he is clearly one of its pioneering professional practicioners. But for (or from) me, just a little introduction. Salem produced a succession of eminent antiquarians—-Joseph B. Felt, Sidney Perley, George Francis Dow—so calling Henry F. Waters the most eminent is a big statement, but I think he was: his combinantion of intense genealogical research and incessant collecting gave him a very public status in the later years of his life, and after. And he was the New England Historical and Genealogical Society’s first “foreign agent!” In the obituary written by his friend and Harvard classmate James Kendall Hosmer for the January 1914 issue of the NEHGS’s Register, Hosmer calls Waters “the most eminent antiquarian of his time, perhaps of all times,” so I am just following suit.

Waters in his uniform at the beginning of the Civil War (he served with Co. F, 23rd Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers until he came down with rheumatic fever followed by yellow fever and then in hospitals after his recovery) and in the facing pages of his publications; portrait by Salem artist Isaac Caliga in the bottom right corner.

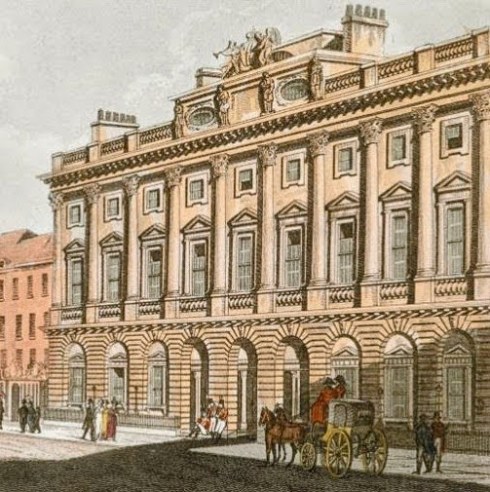

Waters grew up in Salem and went on to Harvard and service during the Civil War, after which he returned to his native city and dabbled according to Hosmer: he “was engaged not earnestly in educational work, collected old furniture, and pored over old documents.” He lived with his parents and unmarried brothers at 80 Washington Square, a c. 1795 McIntire mansion on Salem Common which belonged to his mother’s family (the Townends—who seem to be the reason for his ability to dabble, though his father was a judge). This house was obviously very important to him, as it was his primary residence for his entire long life, but I believe that another “house” was even more important to him: Somerset House in London, a grand classical building on the Strand which is now an arts center, but was the principle probate records repository during Waters’ lifetime—and long after. Waters went to London for the first time in 1879 with his friend Dr. James A. Emmerton (a medical doctor who also preferred to dabble) and they dove into these and other records, looking for anything and everything that might pad the pedigrees of New England families. They were very successful, and published genealogical “gleanings” in both the Historical Collections of the Essex Institute and the Register. Requests for more research were forwarded to both institutions, and in 1883 Waters returned to London as the first salaried “agent” of the New England Historical and Genealogical Society. He remained there (with occasional trips back home) for the next 17 years, during which he traced the lineages of just about every Salem mercantile family and established a national reputation through the continual publication of his genealogical research in journals and books as well as his detailed ancestries of John Harvard, Roger Williams, and George Washington.

80 Washington Square in the 1890s, Frank Cousins Collection at the Phillips Library via Digital Commonwealth; Somerset House in London, Rudolph Ackermann, 1809, British Library; An Examination of the English Ancestry of George Washington: Setting Forth the Evidence to Connect Him with the Washingtons of Sulgrave and Brington (1889).

Waters is credited by his contemporaries with “historical” discoveries as well as genealogical ones: I’m always a bit suspect of archival “discoveries” as that word slights the efforts of archivists, something I am always reluctant to do! But Waters brought several seventeenth-century maps to light, at least over here, including what became known as the “Winthrop-Waters Map” of the coast of Massachusetts c. 1630 and a colored map of Boston Harbor in 1694 which he had copied, as well as Samuel Maverick’s Briefe discription of New England and the severall townes therein: together with the present government thereof (1661) which had been purchased by the British Library several years before his arrival in London. I really think we should term these American discoveries, but they are very much in keeping with Water’s role as a retriever of textual and material heritage.

Copy of “A Draught of Boston Harbor: By Capt. Cyprian Southake, made by Augustine Fitzhugh, Anno 1694;” made for H. F. Waters, Esq., from the original in the British Library, copyright New England Historical and Genealogical Society.

This was a man who was appreciated during his lifetime, and after, but I think there is still more to discover and emphasize about him. We could embellish his role as Colonial Revival “influencer”: former Peabody Essex Museum curator Dean Lahikainen emphasized this role in relation to Salem artist Frank Weston Benson in the PEM’s 2000 Benson exhibition. Waters had tutored Benson and his brothers who grew up nearby on Salem Common and several of Benson’s paintings featuring interiors included items from the Waters collection or inspired by it. I think that Waters’ educational roles are a bit underemphasized: he was a gentleman tutor for sure: but he also held formal teaching positions at different times in his life and served on the Salem School Committee. His family is very interesting: he proudly served in the Massachusetts Massachusetts 23rd and in the medical corps, but several of his Waters cousins owned and operated plantations in the south—in Georgia and Louisiana (The Waters Family papers at the Phillips Library in Rowley will yield many “discoveries”, I am certain). And there is also more to say about his genealogical methodology, which I think would be of interest to contemporary genealogists. Salem is projecting a strong and rather stodgy heritage profile during the dynamic Gilded Era, and Mr. Waters was one of its most prominent exemplars.

The first Cabot house in Salem, built in John Cabot in 1708 at what is now 293 Essex Street; demolished in 1878: this is a great photo because you can see how commercial architecture imposed on Salem’s first great mansions on its main street.

The first Cabot house in Salem, built in John Cabot in 1708 at what is now 293 Essex Street; demolished in 1878: this is a great photo because you can see how commercial architecture imposed on Salem’s first great mansions on its main street. Moved to Danvers! No time to run over there and see if it is still standing right now, but will update when I know.

Moved to Danvers! No time to run over there and see if it is still standing right now, but will update when I know. Oh my goodness look at this Beverly jog! Built by second-generation Dr. John Cabot in 1739. Church Street was destroyed by urban renewal and is a shadow of its former self.

Oh my goodness look at this Beverly jog! Built by second-generation Dr. John Cabot in 1739. Church Street was destroyed by urban renewal and is a shadow of its former self. A familiar corner at the 299 Essex Street and North Streets: this Cabot house was built in 1768 by Francis Cabot and later occupied by Jonathan Haraden.

A familiar corner at the 299 Essex Street and North Streets: this Cabot house was built in 1768 by Francis Cabot and later occupied by Jonathan Haraden.

Survived! The Cabot-Endicott-Low House was built in 1744 by merchant Joseph Cabot and remains one of Salem’s most impressive houses. Its rear garden used to extend to Chestnut Street, and crowds would form every Spring to gaze upon it.

Survived! The Cabot-Endicott-Low House was built in 1744 by merchant Joseph Cabot and remains one of Salem’s most impressive houses. Its rear garden used to extend to Chestnut Street, and crowds would form every Spring to gaze upon it.

Indian Muslin and silver wedding reception dress of Sarah Ellen Derby Rogers, 1827, Peabody Essex Museum (Gift of Miss Jeannie Dupee, 1979).

Indian Muslin and silver wedding reception dress of Sarah Ellen Derby Rogers, 1827, Peabody Essex Museum (Gift of Miss Jeannie Dupee, 1979).