I’ve been obsessed with the work “landmark” ever since the Samantha statue incident of last week: a succession of news stories in the days following reported the vandalism inflicted on this famous Salem “landmark” and each time I heard or read that term applied to this horror installation I screamed “she is not a landmark!” in my head. Isn’t a landmark something notable, of value, an attribute of place or a place itself, but nevertheless something we admire and want to preserve? Several people pointed out that the word doesn’t have to connote subjective judgements: it is merely something recognizable. I’ve just written a book which has chapters on both surveying and navigation, so you’d think I’d be a bit more confident in my understanding of this term. Its original use in navigation refers to a physical feature of the land with which you can find, or mark, your way, but I thought its meaning evolved in the past centuries with respect to architecture, historic preservation, and the recognition and designation of built landmarks. My understanding of the term is coming more from those fields, so using the same term to apply to Samantha and say, the Ropes Mansion just seems wrong! Clearly it is time to look this word up, so I went straight to the Oxford English Dictionary (I am fortunate to have an institutional subscription but I go there only when I really need to, as it is a rabbit hole for me. But needs must.)

LANDMARK: object marking a boundary line; district;

2. An object in the landscape, which, by its conspicuousness, serves as a guide in the direction of one’s course (originally and esp. as a guide to sailors in navigation); hence, any conspicuous object which characterizes a neighbourhood or district.

3. (In modern use.) An object which marks or is associated with some event or stage in a process; esp. a characteristic, a modification, etc., or an event, which marks a period or turning-point in the history of a thing.

Ok, I’m going with the second part of #2 “any conspicuous object which characterizes a neighborhood or a district.” The key word for me here is characterizes. I’m just not comfortable with Samantha characterizing Salem: I want Samuel McIntire to characterize Salem. But obviously there has to be some sort of standard for designating a landmark, or is it all subjective? To try to answer this last questions, I decided to do a search for “Salem Landmark” in all of my newspaper databases. This query produced hundreds of hits, but I quickly determined that many of these references were to the Salem Landmark newspaper of 1835-36 which first published the wildly popular “Enquire at Amos Giles’ Distillery” temperance parable, which was reprinted all over the country. So I eliminated those entries, and came up with a clear succession of Salem landmarks.

For the most part, the word landmark was used in referenced to historic buildings in Salem, but there were some exceptions. Beginning in the 1870s, there seems to be an emerging concern that Salem is losing its historic structures because there is a succession of titles to the tune of “another Salem landmark gone.” Clearly the word could be used to ascertain an increasing interest in historic preservation, but it’s not just about loss: landmark appears when particularly old or otherwise notable buildings are sold or “substantially altered,” when there’s a fire, or some event happens in a well-know location. Here’s a few examples, starting with the “old Putnam Estate on Essex Street,” a house with which I’m not immediately familiar—I’m not quite sure about this Bridge/Osgood Street house either, but it has an interesting story! Sounds like part of it might still be around?

It’s easy to get caught up in the stories attached to these old buildings: I did so several times and forgot all about Samantha (which is good)! The two above are a bit more obscure landmarks, but anything to do with Nathaniel Hawthorne, Samuel McIntire, the Witch Trials, the Revolutionary War, and political leaders or wealthy Salem merchants were designated as such. Sometimes I think the word was used a little loosely: a sailcloth factory? Well, it was a sailcloth factory that belonged to the legendary Billy Gray and was the studio of Ross Turner: I hope he didn’t lose any paintings! I had heard about the threat to the Pickering House before, which is why I am not expressing shock and awe now. Everything else below is pretty self-explanatory, but I should report the the Silsbee/Knights of Columbus mansion has just been completely restored and expanded and it looks great.

Besides Derby Wharf (above), the only designated landmarks I could find which were not buildings were a landmark store which closed after 114 years in business, and the famed “Brown’s Flying Horses” of Salem Willows. This carousel had been a major attraction of Salem Willows since the 1870s, and its sale to Macy’s Department Store in 1945 was big news and a big loss. By all accounts, it was a beautiful example of craftsmanship by a Bavarian woodworker, so comparing it to Samantha is a stretch, but both were/are popular “attractions,” so I guess that’s the landmark connection. I think I’ve worked myself out of my landmark labyrinth, but I’m still troubled by placement: certainly nothing could be more evocative and appropriate in a seaside amusement park than a carousel, but I still don’t think Samantha belongs in Town House Square.

Apparently this business had started in 1794 by the Driver Family and was run by relatives or in-laws until 1908, Boston Sunday Globe, September 20, 1908. Brown’s Flying Horses at Salem Willows, photographs from the “Essex Institute”/Phillips Library via Painted Ponies: American Carousel Art by William Manns et. al.

Beard Collection, Victoria and Albert Museum.

Beard Collection, Victoria and Albert Museum.

All the wives, plucky Anne, personal Tudor history from the last century, and Hans Holbein re-envisioned by

All the wives, plucky Anne, personal Tudor history from the last century, and Hans Holbein re-envisioned by

The last photograph of the last Tsar, Nicholas II, and his family, at the Ipatiev House in Yekaterinburg, where they were executed in the early hours of July 17, 1918.

The last photograph of the last Tsar, Nicholas II, and his family, at the Ipatiev House in Yekaterinburg, where they were executed in the early hours of July 17, 1918.

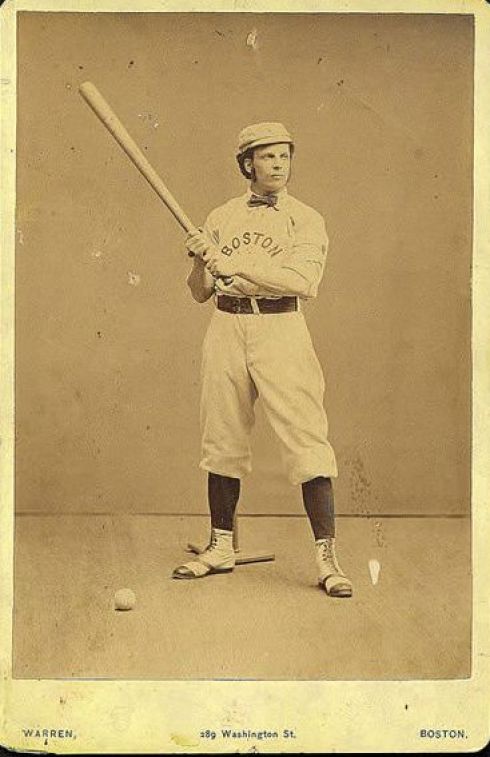

The Base Ball Player’s Pocket Companion. Boston: Mayhew and Baker, 1859.

The Base Ball Player’s Pocket Companion. Boston: Mayhew and Baker, 1859.

All images from Robert Edward

All images from Robert Edward  Baseball Sheet Music

Baseball Sheet Music