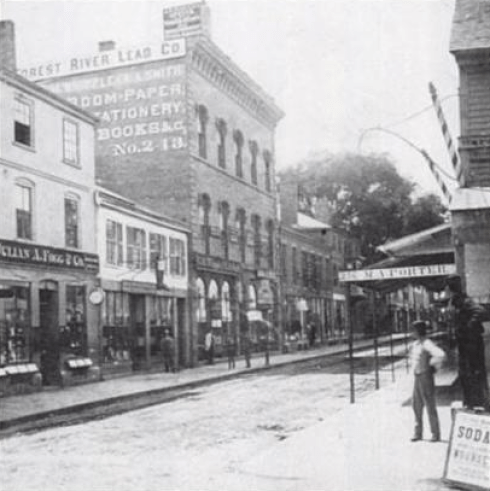

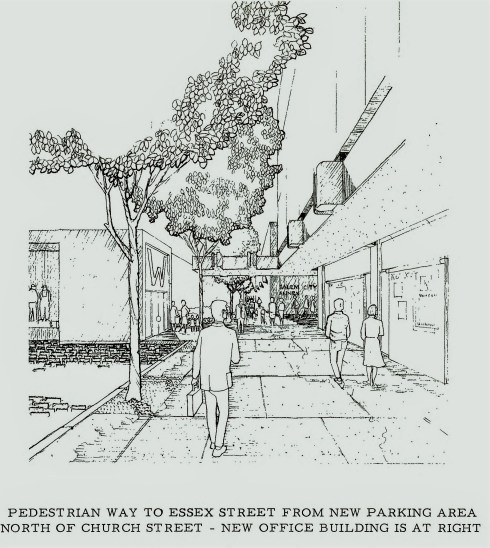

I have heard, and read about, Salem’s experience with urban renewal many times, including first-hand accounts, so I thought I understood its causes, course and impact pretty well, but when you write about something, you have to engage on another level and come to your own understanding in order to explain it to others. It’s the same with teaching. One of the chapters for Salem’s Centuries that I’ve been working on this summer is about the city’s development over the twentieth century and so I really had to dig deep into urban renewal. I decided to start fresh with primary sources, so I went through all the records of the Salem Redevelopment Authority (SRA) located up at the Phillips Library in Rowley (these are public records, which should be in Salem, but I’m actually glad they are in Rowley because the City’s digitized records are impossible to search and I don’t know how one might access the paper). The SRA was the agency created to oversee urban renewal in Salem’s downtown and it still has jurisdiction: its composition was incredibly important and remains so. I’m going to be quite succinct here, because the narrative is rather complex and therefore quite boring to read or write about, but here’s the gist of what happened: after conducting a comprehensive study in the early 1960s the City created the SRA and put forward a very ambitious urban renewal plan which was overwhelmingly focused on clearance, including the demolition of between 120-140 buildings in Salem’s downtown area. The goal was to create a new pedestrian shopping plaza, to compete with the new Northshore Shopping Center just miles away in Peabody. The focus was on Parking, Parking, and more Parking. What I did not know before I delved into this research was that at the same time that this plan was brewing, Salem also had another committee looking at the downtown: an Historic District Study Committee, which was surveying all of central Salem’s buildings for inclusion in potential historic districts. What a clash! The “before” photos that you see below, candid polaroids, were taken by members of the Study Committee in 1965, the same year that the SRA was rolling out its demolition plan. Among the SRA records up in Rowley, there is a mimeographed document entitled a “Do it Yourself Walking Tour” prepared by John Barrett, Executive Director of the SRA, for Historic Salem, Inc., Salem’s preservation organization, then and now. It’s a remarkable document, because Barrett basically takes the Study Committee’s inventory and turns it into a hit list: this is what we’re going to demolish! Take a tour and see for yourself! There were 119 building slated for demolition, a number that would expand to over 140 over the next few years. The polaroids represent buildings that Salem’s preservationists were trying to save: they were successful in some cases, but not in others. Their resistance resulted in a far less destructive approach to “renewal”, however, which focused more on rehabilitation than destruction, as these images illustrate well.

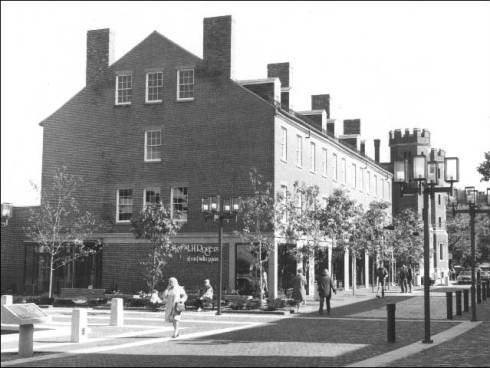

This doesn’t line up perfectly, but what a great restoration +addition by Salem architect Oscar Padjen: very representative of the creativity of “Plan B”!

This doesn’t line up perfectly, but what a great restoration +addition by Salem architect Oscar Padjen: very representative of the creativity of “Plan B”!

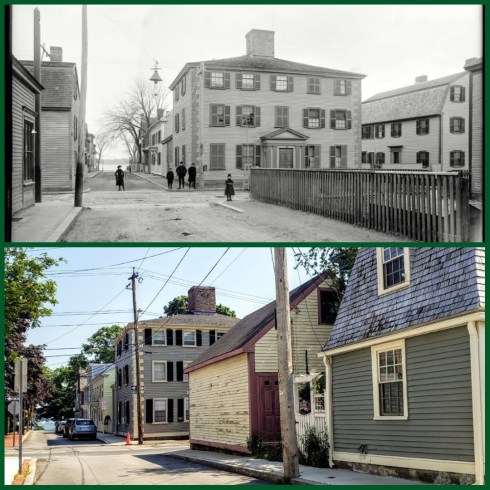

As these photos also illustrate, once rehabilitation became an objective, several key buildings were restored in exemplary fashion, by local Salem architects and utilizing the new means of facade easements. If you compare past facades of these building with the present, urban renewal looks great, particularly with the hardscaping design of landscape architect John Collins of Philadelphia, whose work is also representative of the “Plan B” approach. What is more difficult to illustrate are the great wide swaths of buildings that were taken down, principally on the main Essex and Federal Streets but also on St. Peter and Brown Streets, while Plan A was still operational. We can never see these buildings restored, they were just swept away. What remains are parking lots and ghastly modern buildings. I’m not a fan of what was called the East India Mall in its orginal incarnation, but its colonnaded side entrance (not quite sure what to call it???) was quite distinctive, and it was butchered under the auspices of the SRA in the 1990s so now we have the Witch City Mall. I think Front Street (below) it probably the most perfect example of Plan B, along with Derby Square, but Central Street (just above) is pretty representative too.

Washington Street was the boundary of “Heritage Plaza East,” where most of the renewal activity happened in both phases, but it did not experience as much demolition as it had already weathered a major tunnel project just a decade before. That’s another realization for me: I somehow never put Salem’s “Big Dig,” during which its railroad tunnel was constructed and depot demolished in the 1950s, in such close chronological proximity to its experience with urban renewal in the 1960s. This generation of Salem residents weathered a lot of construction and dislocation: as always, past experiences temper the present. If you shift the perspective even further back, to the 1930s, when the new Post Office was built after an entire neighborhood was cleared out, you can understand why there is so much concern about the lack of housing downtown today: 51 buildings gone in the 1930s, 87 in the 1960s. Salem’s long “plaza policy” certainly took its toll, but I remain grateful to those residents who persevered in their preservation efforts for what remains.

Strking transformations on Washington Street.

NB: I’m confident in most of these past-and-present pairings, but not all, because streets numbers can change—not quite sure about the Subway market on Front Street for example……….

The first Cabot house in Salem, built in John Cabot in 1708 at what is now 293 Essex Street; demolished in 1878: this is a great photo because you can see how commercial architecture imposed on Salem’s first great mansions on its main street.

The first Cabot house in Salem, built in John Cabot in 1708 at what is now 293 Essex Street; demolished in 1878: this is a great photo because you can see how commercial architecture imposed on Salem’s first great mansions on its main street. Moved to Danvers! No time to run over there and see if it is still standing right now, but will update when I know.

Moved to Danvers! No time to run over there and see if it is still standing right now, but will update when I know. Oh my goodness look at this Beverly jog! Built by second-generation Dr. John Cabot in 1739. Church Street was destroyed by urban renewal and is a shadow of its former self.

Oh my goodness look at this Beverly jog! Built by second-generation Dr. John Cabot in 1739. Church Street was destroyed by urban renewal and is a shadow of its former self. A familiar corner at the 299 Essex Street and North Streets: this Cabot house was built in 1768 by Francis Cabot and later occupied by Jonathan Haraden.

A familiar corner at the 299 Essex Street and North Streets: this Cabot house was built in 1768 by Francis Cabot and later occupied by Jonathan Haraden.

Survived! The Cabot-Endicott-Low House was built in 1744 by merchant Joseph Cabot and remains one of Salem’s most impressive houses. Its rear garden used to extend to Chestnut Street, and crowds would form every Spring to gaze upon it.

Survived! The Cabot-Endicott-Low House was built in 1744 by merchant Joseph Cabot and remains one of Salem’s most impressive houses. Its rear garden used to extend to Chestnut Street, and crowds would form every Spring to gaze upon it. Caroline O. Emmerton, The Chronicles of Three Old Houses, 1935

Caroline O. Emmerton, The Chronicles of Three Old Houses, 1935 Louise duPont Crowninshield (center) surrounded by the ladies of the Kenmore Association in Virginia, one of her first preservation projects, Hagley Museum & Library.

Louise duPont Crowninshield (center) surrounded by the ladies of the Kenmore Association in Virginia, one of her first preservation projects, Hagley Museum & Library.

Seeing red (demolition) in 1965; 7 Ash Street, the Bessie Munroe House, today.

Seeing red (demolition) in 1965; 7 Ash Street, the Bessie Munroe House, today. Ada Louise Huxtable’s condemnation of Salem’s 1965 Urban Renewal Plan in October of that year, the first of several pieces published in the New York Times.

Ada Louise Huxtable’s condemnation of Salem’s 1965 Urban Renewal Plan in October of that year, the first of several pieces published in the New York Times. 1965! What a year that must have been—-Salem’s preservationists had to have been functioning 24/7.

1965! What a year that must have been—-Salem’s preservationists had to have been functioning 24/7. A Boston Globe (glowing) review for Ms. Farnam’s exhibition, Dr. Bentley’s Salem. Diary of a Town in 1977 and 1992 photograph of Ms. Pollack.

A Boston Globe (glowing) review for Ms. Farnam’s exhibition, Dr. Bentley’s Salem. Diary of a Town in 1977 and 1992 photograph of Ms. Pollack.

The John P. Felt House on Federal Court past and present: despite a rough last half-century or so, the house is still standing in good form, lacking only its widow’s walk and shutters.

The John P. Felt House on Federal Court past and present: despite a rough last half-century or so, the house is still standing in good form, lacking only its widow’s walk and shutters. Barton Square has been pretty much annihilated.

Barton Square has been pretty much annihilated. Change and continuity on Bott’s Court: old house on the left, newer (both 1890s) houses on the right. Cousins is showing us the demolition of the former house on the right with his preservationist eye.

Change and continuity on Bott’s Court: old house on the left, newer (both 1890s) houses on the right. Cousins is showing us the demolition of the former house on the right with his preservationist eye. Kimball Court present and past: Cousins is showing us the birthplace of Nathaniel Bowditch below: this house is in the top right corner above. In front of it today is a house that was brought over from Church Street during urban renewal in the 1960s when that street was wiped out.

Kimball Court present and past: Cousins is showing us the birthplace of Nathaniel Bowditch below: this house is in the top right corner above. In front of it today is a house that was brought over from Church Street during urban renewal in the 1960s when that street was wiped out. 18 Lynde Street: this appears to be the same house, with major doorway changes.

18 Lynde Street: this appears to be the same house, with major doorway changes. The house on Mall Street where Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote the Scarlet Letter: there was an addition attached to the house at some point in the 1980s or thereabouts.

The house on Mall Street where Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote the Scarlet Letter: there was an addition attached to the house at some point in the 1980s or thereabouts. 134 Bridge Street: As a major entrance corridor–then and now—Bridge Street has impacted by car traffic pretty dramatically over the twentieth century; Cousins portrays a sleepier street with some great houses, many of which are still standing—hopefully the progressive sweep of vinyl along this street will stop soon.

134 Bridge Street: As a major entrance corridor–then and now—Bridge Street has impacted by car traffic pretty dramatically over the twentieth century; Cousins portrays a sleepier street with some great houses, many of which are still standing—hopefully the progressive sweep of vinyl along this street will stop soon. 17 Pickman Street seems to have acquired a more distinguished entrance; this was the former Mack Industrial School (Cousins’ caption reads “Hack” incorrectly).

17 Pickman Street seems to have acquired a more distinguished entrance; this was the former Mack Industrial School (Cousins’ caption reads “Hack” incorrectly). Great view of lower Daniels Street–leading down to Salem Harbor–and the house built for Captain Nathaniel Silsbee (Senior) in 1783. You can’t tell because of the trees, but the roofline of this house has been much altered, along with its entrance.

Great view of lower Daniels Street–leading down to Salem Harbor–and the house built for Captain Nathaniel Silsbee (Senior) in 1783. You can’t tell because of the trees, but the roofline of this house has been much altered, along with its entrance. Hardy Street, 1890s and today: with the “mansion house” of Captain Edward Allen still standing proudly on Derby Street though somewhat obstructed by this particular view. You can read a very comprehensive history of this house

Hardy Street, 1890s and today: with the “mansion house” of Captain Edward Allen still standing proudly on Derby Street though somewhat obstructed by this particular view. You can read a very comprehensive history of this house

The old Naumkeag Trust Bank Building (1900), soon to be Count Orlok’s Nightmare Gallery; Museum Place (Witch City Mall) shops and signs, today and in the 1970s (MACRIS and Bryant Tolles’ Architecture in Salem).

The old Naumkeag Trust Bank Building (1900), soon to be Count Orlok’s Nightmare Gallery; Museum Place (Witch City Mall) shops and signs, today and in the 1970s (MACRIS and Bryant Tolles’ Architecture in Salem).