Norman Street was and is an important thoroughfare in Salem, one of the major connections from the major route north to the center of the city, and ultimately the harbor. The street was charming in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with substantial houses lining its brick sidewalks and TREES. Two of my favorite Salem Georgians were on Norman, the Jonathan Mansfield House and the Benjamin Cox House: details of the former show up in all sorts of early American architecture books in the first few decades of the twentieth century.

Norman Street in the later nineteenth century (1880s-1890s), Phillips Library, Peabody

Norman Street was essentially annihilated in the twentieth century: its charming houses demolished and replaced by generic business boxes, its width expanded for automobiles, its trees left to die. I can’t think of a street in Salem so utterly transformed. Its bleakness is all the more apparent by the fact that it’s basically an extension of mansion-lined Chestnut Street, so the contrast is striking: I sigh with relief when I pass over Summer Street and everything gets greener and more friendly. All the twentieth-century forces aligned to kill this street: a big public works project (the Post Office), the car, of course, and the worst architectural eras of the century, the 1930s and the 1970s-1980s. There are three crosswalks, but cars whip around the corner onto Norman so you have to be a rather audacious pedestrian to think about using them. The street is so bleak it can only be improved, but the one vacant lot now set for redevelopment is in a particularly conspicuous spot: on a corner, between two historic districts, and between a residential district and the beginning of the commercial downtown: this project has the potential to CONNECT so many constituent parts of Salem, and restore some structure (and dignity) to Norman Street at the same time. I have high hopes and great expectations, and I really hope the permitting boards of Salem do too.

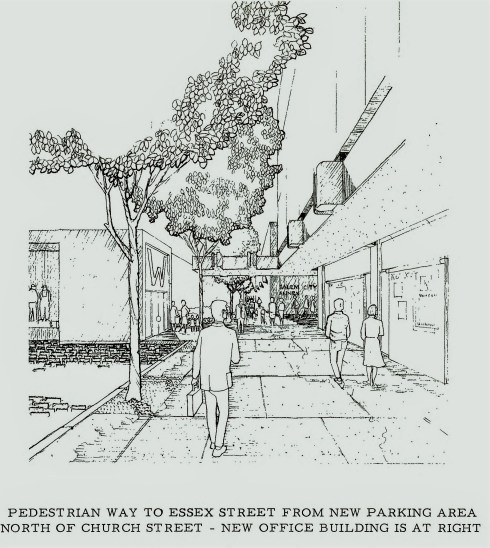

So let me show you the current lot and the prospective building: I am taking these photos from the presentation that the developers (Kinvarra Capital) and Architects (Balance Architects) gave to a neighborhood group last week, before they go before the Salem Redevelopment Authority (SRA) next week. This presentation was very thorough in its consideration of all of the challenges and context of this site, I thought. You can see the whole thing for yourself here. Let me say that I don’t have really strong objections to this building: compared to recent construction in Salem, and to what defines Norman Street at present, it’s an improvement. But I think it could be better. And I REALLY think that it should prompt a city-wide discussion about design rather than just a neighborhood discussion about parking.

Existing conditions looking north (top) and east (bottom): Chestnut Street is right behind you in this second photo. The city has decided to put a roundabout at this busy intersection, but they haven’t really committed and it’s too small a space, so everyone just drives over that yellow circle.

Same vantage points as above with the rendering of the new building. The bottom image also show the recently-approved “suburban” addition to the adjacent Georgian house by the Salem Redevelopment Authority (SRA), the same board that has jurisdiction over new Norman Street building.

So you see, a challenging site. I don’t envy the architects: should they take their contextual cues from the adjacent 1980s plaza, or the Georgian with its (insert adjective; I have no words) addition, or the 1930s Holyoke building across the street or the Federal and Italianate buildings which open Chestnut Street? You know me, I’m a traditionalist and a historian: I’d like to restore something of what was Norman Street in its glory days, perhaps along the lines of the Julia Row in New Orleans, without the wrought iron. But you can’t really recreate that: it would look cheap with today’s materials, and it wouldn’t fit in with the twentieth-century buildings of Norman Street. It’s not the entire composition but rather the depth of façade and detail I’m after, and in this case I was particularly attracted to the parapet end wall: if integrated into a new building on Norman, it could match the one at 2-4 Chestnut Street, establishing continuity and connection.

Julia Row, New Orleans; Chestnut and Norman Streets in the 1880s, Salem Picturesque, State Library of Massachusetts.

The New Orleans building is also too big, as is the proposed Norman Street building. What you don’t see in these photographs is the Crombie Street Historic District tucked away in back, with smaller-scaled buildings than any of the other adjacent structures. I looked at some recent developments in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia in which new construction was integrated into existing historic neighborhoods and came up with a few favorites in terms of scale and also texture, which is missing in most of the new construction I see. The first is in Bay Village in Boston, a small historic neighborhood tucked away in the midst of downtown Boston. The scale and detail of of Piedmont Park Square is nice: it fits right into its quaint neighborhood on the storied site of the Cocoanut Grove, where a tragic fire occurred in 1942. The building “stitches” together townhouses—what could be more connective than that?

Piedmont Park Square in Boston’s Bay Village by Studio Luz Architects.

As I searched for semblances of things I’d like to see in this important new building, I was motivated by scale, detail, texture, integration, contextuality, and some sense of the past: the proposed rendering reads “industrial” to me, and Norman Street was never industrial, so I don’t understand the reference. I don’t think I found what I was looking for, but I really like the integration achieved by a recent infill development in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, below. Tucked in between an early 20th century mansion on the site of its fire-ravaged garage and a row of 19th-century townhouses, this structure fits in but still makes a statement with its variegated façade and roofline and so much texture! This seems like an even more difficult challenge than Norman Street. I like it, but my husband-the-architect does not and neither, apparently, do its neighbors. All architecture is paradoxical, but urban architecture particularly so: it is so very public, yet the public has so little power to influence what is built.

Renderings of 375 Stuyvesant Street, Brooklyn by DXA Studio.

Like this:

Like Loading...

William Pierce Stubbs, Bark Taria Topan of Salem, 1881, Bourgeault-Horan Antiquarians; The Salem Marine Society Room at the top of the Hawthorne Hotel, The Bark Glide of Salem.

William Pierce Stubbs, Bark Taria Topan of Salem, 1881, Bourgeault-Horan Antiquarians; The Salem Marine Society Room at the top of the Hawthorne Hotel, The Bark Glide of Salem.

Miller notices: Salem Gazette, 1.17.1856; Salem Observer, 7.16 1864, Salem Observer, 9.22.1860; Salem Register, 1.12. 1857; The cabin-like Great Hall at Stonehurst, built by Miller.

Miller notices: Salem Gazette, 1.17.1856; Salem Observer, 7.16 1864, Salem Observer, 9.22.1860; Salem Register, 1.12. 1857; The cabin-like Great Hall at Stonehurst, built by Miller.