As I’ve been finishing up the manuscript of our 4o0th anniversary volume, Salem’s Centuries, I’ve been writing and thinking about Salem’s 300th anniversary quite a bit. For some reason I thought that I had already posted about this big event on this unwieldly blog, but I haven’t. Quite a lot is out there—the archivists at the Salem State University Archives and Special Collections oversee an ever-larger collection of historical photographs of Salem, many of which they have uploaded to Flickr, and among them are some great Tercentenary views. This is really the best place to go for local history, including an array of blog posts which put their collections in context. So maybe, in my writing-and-teaching-brain-fog, I confused their output for mine? I don’t know, but there’s certainly no Tercentenary post here so I thought I’d pull one together. I’m quite impressed by the activity of the 1926 Tercentennial but it was certainly more celebration than reflection. This was not a moment to be at all critical about the city’s past; this was a party! Beginning on July 3, 1926 and commencing on the 10th, city residents were feted by parades, street parties, reunions, balloon ascensions, a big ball, a field day, a firemen’s muster, a bonfire, various illuminations, and concerts, concerts, and more concerts. Many people were involved in the planning, at least hundreds if not more. Starting in 1924 a general committee came together, followed by the appointment of chairs of the various subcommittees: the bonfire, music, fireworks, the horribles parade, sports, the military, civic, and historical parade, historical exercises, banquet, costume ball, floral parade, firemen’s muster, entertainment and publicity. Then the work began and there were some alterations: a “great” civic and military parade was severed from the floral and historical parade when it became apparent that the consolidated parade would be very, very long and that the guest of honor, Vice-President George Dawes, could be in Salem only for a short period of time. (President Coolidge was invited to the Tercentenary shortly after his election and I have no idea why he couldn’t turn up—it seems like a slight, as didn’t he summer in Swampscott?) The planning seemed to go smoothly but I have no real insights into subcommittee deliberations—I’m not sure where the meeting meeting minutes are, or if there were any. But they seem to have thought of everything, including a temporary “hospital” installed in the Phillips School overlooking Salem Common. The one big pre-celebration problem that surfaced was in relation to one of the big arches erected at the entrances to the city, specifically the arch at the Salem-Beverly Bridge. Once completed, a furor arose: it said “Greetings” rather than “Welcome” and on the wrong side! Greetings was simply not welcoming enough, and people leaving the city and crossing over to Beverly were being greeted! It cost the princely sum of $700 to fix this arch sign but it had to be fixed and so fixed it was.

I think that was it for the missteps, and then came July, and they were off! Here’s the schedule:

Sunday the 4th: Bells ring all over the city, followed by religious services, and then a huge band concert on the Common. Presumably this is what the brand new bandstand was built for, but as the band consisted of “300 pieces” I don’t think all those musicians could have fit in there. In the evening, a 100-foot bonfire was set ablaze (we are right in the midst of Salem’s big July 4th bonfire craze at this time).

Monday the 5th: The “Grotesque, Antiques & Horribles Parade” featuring Salem schoolchildren in costume competing for prizes (this is another Salem/North Shore July 4th tradition).

We are the Freaks Float, Nelson Dionne Salem History Collection, Salem State University Archives and Special Collections, Salem, Massachusetts.

We are the Freaks Float, Nelson Dionne Salem History Collection, Salem State University Archives and Special Collections, Salem, Massachusetts.

Tuesday the 6th: Tours of old Salem homes open for the occasion, many, but not all, on Chestnut Street, and an exhibition of “treasures brought to Salem by the sea captains of old days.” In the evening, a balloon ascension at Salem Willows and an “illumination” of US Navy vessels in Salem Harbor.

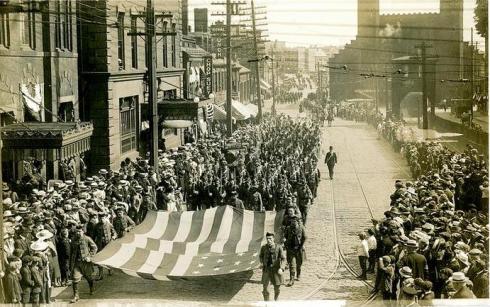

Wednesday the 7th: the “Great” Parade, with Vice-President Dawes in attendance. This was followed by an historical address on Salem Common, another band concert, and fireworks.

Vice President Charles G. Dawes, Mayor George J. Bates, Governor Alvan T. Fuller, and Congressman William M. Butler; Nelson Dionne Salem History Collection, Salem State University Archives and Special Collections, Salem, Massachusetts.

Vice President Charles G. Dawes, Mayor George J. Bates, Governor Alvan T. Fuller, and Congressman William M. Butler; Nelson Dionne Salem History Collection, Salem State University Archives and Special Collections, Salem, Massachusetts.

Thursday the 8th: Family reunions for “Old Planter” families; I’m not sure about everyone else. The first Chestnut Street Day, which was quite the event, and a field day on the Common. The Tercentenary Ball was held that evening at Salem Armory.

Friday the 9th: The other parade, the “Floral and Historical Parade.” (I just love the idea of this– flowers and history!)

Floral Float No. 9, 1926 and Brig Leander Float, Leland O. Tilford photographs, Salem News Historic Photograph Collection, Salem State University Archives and Special Collections, Salem, Massachusetts.

Saturdy the 10th: A huge firemen’s muster on Salem Common, yet another parade and band concert, and fireworks on Gallow Hill.

Quite a success I think, and there were some cultural consequences too. One thing I’m curious about is Salem artist Phillip Little’s “huge” painting of Derby Wharf at the beginning of the nineteenth century: it was commissioned by the Naumkeag Steam Cotton Company for a big home exposition in the spring of 1926 and supposedly shown in Salem for the Tercentenary, but I’m not sure where or when. And where is it now? I want to see it! Since I have not seen it, I have to say that my favorite Salem Tercentenary painting remains Felicia Waldo’s impressionistic view of the first Chestnut Street Day.

Felicie Waldo Howell, Salem’s 300th Anniversary, 1926, Christies.

Felicie Waldo Howell, Salem’s 300th Anniversary, 1926, Christies.

These civic celebrations can seem frivolous on the surface, but they also reveal a lot about the communities which are putting them on. Much of these activities would have been very familiar to Salem people in 1926: they were used to parades, and old home days, bonfires and annual field days, in which children from every neighborhood competed against each other in a variety of athletic activities on Salem Common. It’s a huge generalization which deserves much more documentation and explanation, but Salem seems much more focused on its residents than its visitors at this time, and for much of the twentieth century. The comments and the coverage from 1926 indicate that what was really new about the Tercentenary were the open historic houses throughout the City, and on Chestnut Street in particular. The national house and garden magazines went crazy with the coverage! Chestnut Street Day was so successful that it was repeated on four more occasions, with the last one occurring in 1976 (there are some great Samuel Chamberlain photographs of later Chestnut Street days from the Phillips Library at Digital Commonwealth and here). And there was nary a witch in sight in 1926, certainly not on the official Tercentenary medal.

Some different perspectives on Mill Hill beginning with the 1897 Atlas at the State Library of Massachusetts. The first view is looking NORTH, towards downtown Salem, the rest are looking SOUTH towards Lafayette Street. The Phillips Library via Digital Commonwealth (NORTH), two post-fire scenes from the Salem State University Archives and Special Collections, and another Phillips Library view from about ten years later, after considerable post-fire reconstruction. Of course, the old St. Joseph’s–and the new St. Joseph’s–are long gone.

Some different perspectives on Mill Hill beginning with the 1897 Atlas at the State Library of Massachusetts. The first view is looking NORTH, towards downtown Salem, the rest are looking SOUTH towards Lafayette Street. The Phillips Library via Digital Commonwealth (NORTH), two post-fire scenes from the Salem State University Archives and Special Collections, and another Phillips Library view from about ten years later, after considerable post-fire reconstruction. Of course, the old St. Joseph’s–and the new St. Joseph’s–are long gone.

Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

Wallpaper “Froebel” frieze, 1905, E.J. Walenta for Wm. Campbell Wall Paper Company, Machine-printed on paper, Hackensack, New Jersey, USA, Cooper-Hewitt Museum, gift of Paul F. Franco, 1938-50-15.

Wallpaper “Froebel” frieze, 1905, E.J. Walenta for Wm. Campbell Wall Paper Company, Machine-printed on paper, Hackensack, New Jersey, USA, Cooper-Hewitt Museum, gift of Paul F. Franco, 1938-50-15.

Brunswick chairs c. 1958 from the VS

Brunswick chairs c. 1958 from the VS