This weekend brings the third annual commemorative reenactment of “Leslie’s Retreat” to Salem, an enthusiastic event that I think everyone enjoys because of its non-commercial, non-1692 focus: at least I do! The reenactment marks an event which might have sparked the American Revolution weeks before Lexington and Concord, if shots had been fired; it was nonetheless a notable occurrence of an armed (and potentially very dangerous) resistance. In late February of 1775 General Thomas Gage, the military governor of Massachusetts, got wind of a store of cannon in Salem and dispatched Lieut. Col. Alexander Leslie and 240 soldiers of the 64th Regiment by ship from Boston to Marblehead on the 26th (a Sunday!), with instructions to march to Salem and seize them. There’s a lot of whispering and distrust in this story as the “Tory” and “Patriot” sides do not seem firm, but several Marblehead patriots rode ahead in Revere-like fashion and warned the people of Salem, and thus “the Sabbath was disturbed”. By the time the soldiers arrived in Salem a crowd had assembled in the vicinity of the (old) North Bridge, as across the North River was the blacksmith’s shop where the cannons were being affixed to field carriages. A prolonged standoff ensued with the drawbridge raised, during which the cannons were moved west, several ending up in Concord, I believe. The bridge was lowered so that Colonel Leslie could fulfill his orders, but it was too late, and so he and his troops turned around and marched back to Marblehead, their ship, and Boston. I’ve written about this event several times (here and here), there’s a nice narrative of events here, and the most insightful accounts are on J.L. Bell’s brilliant blog Boston 1775 (I especially like this post but check this one out too, and this one), so there is no need to go into any more detail, but there are three issues I’d like to raise, two “open” and one relatively new (I think, maybe not, not my period!), all from newspaper accounts written in the weeks after Colonel Leslie’s retreat from Salem.

There is some back-and-forth, especially in the first few weeks after the Retreat, but for the most part the papers are essentially publishing the standard story first published by the Essex Gazette. There are so many details to this story, however, that it’s notable what is put in and what is left out. So here are my “outstanding” issues, in the form of a question and two comments.

How many damn cannon(s) were there in Salem? I can’t lock down the number (and I know “cannon” is plural but I think I have to use cannons here). Apparently General Gage had received reports that old ships’ cannons were being converted in Salem and eight additional cannons had been imported from abroad, while the Essex Register’s report on the Retreat included the assertion that twenty-seven pieces of cannon were removed out of this town, in order to be out of the way of the robbers. I’ve read (and quoted) seventeen cannons, nineteen cannons, and twenty cannons. I think we’ve go to go with the eyewitness account cited by J.L. Bell, in which Samuel Gray, who was nine years old at the time, went into the smithy on the day after and asked how many cannons had been there the day before and was told twelve; understood they were French pieces, and came from Nova Scotia after the late French war; were guns taken from the French; does not know to whom they belonged previous to being fitted up on this occasion. TWELVE. Gray’s remembrances were in response to interviews that Charles Moses Endicott conducted to produce his Leslie’s Retreat; or the Resistance to British Arms, at the North Bridge in Salem, on Sunday, the 26th of February of 1775, which was first published as a separate Proceeding of the Essex Institute in 1856.

(The remembrance and reconstruction of what became known as “Leslie’s Retreat” enable us to see how Salem’s history was collected, preserved and interpreted by the Essex Institute, one of the founding institutions of today’s Peabody Essex Museum. Contrary to the claims of the PEM leadership: yes, the Essex Institute DID function as a historical society, and that’s why its historical collections, including its publications and historical manuscripts and texts assembled in the Phillips Library, constitute an important archive of Salem’s history, and no, no institution is fulfilling that role for Salem now, so the decisions to end the Institute’s interpretation and collection missions and remove its archival collections from Salem will have far-reaching consequences. These decisions were made by Mr. Dan Monroe, and since he has announced his retirement it is time to consider his legacy—and this is a truly momentous one.) Sorry–the spirit of RESISTANCE overwhelmed me!

Back to the question of the cannon(s): for some reason Endicott goes with 17 in his account, which has become classic, but he includes Gray’s number in his footnotes, clearly giving some credence to his claim. I don’t know why we can’t believe the boy: certainly his would have been a crystalline memory.

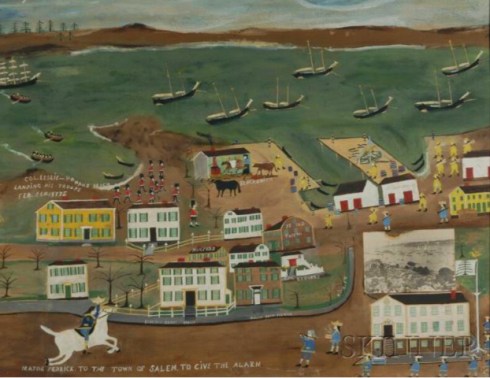

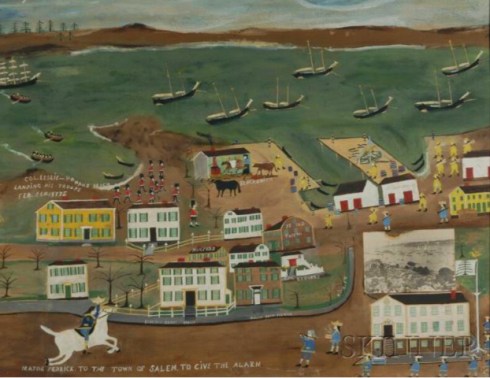

Major Pedrick was a Tory! None of the contemporary reports of the events of February 26, 1775 mention Major John Pedrick as the “alarming” figure who rode ahead of Leslie’s troops to warn the citizens of Salem of their imminent arrival, nor does Endicott. That’s because his role was made up after Endicott’s account. Pedrick was in fact a wealthy Tory who would not have been motivated to play such a conspicuous role at this time; he came around a bit later but anonymous Marbleheaders warned Salem on that Sabbath day. Again, I am relying on J.L. Bell’s succinct analysis of the “myth” of Major Pedrick, which has been perpetuated in the most recent scholarship as well as our reenactment. I was also inspired by Bell’s post to look around and see what else was made up about our event, particularly in the “creative” Marblehead accounts of the later nineteenth century. Samuel Roads Jr.’s History and Traditions of Marblehead (1880) turns Leslie’s Retreat into an all-Marblehead affair: Pedrick is prominent, of course, along with an entire Marblehead Regiment that came to Salem to take up with Leslie’s troops. Not a single Salem name is mentioned in Roads’ account, but we do hear of one Robert Wormsted, one of the young men from Marblehead,—who afterwards distinguished himself by his daring and bravery,—[and ] engaged in an encounter with some of the soldiers. He was a skillful fencer, and, with his cane for a weapon, succeeded in disarming six of the regulars. Wow. No mention in Endicott of this cane-wielding Wormsted—or Pedrick—but Marblehead folk artist J.O.J Frost seems to have cemented the latter’s place in history in his early twentieth-century painting “Major Pedrick. To the Town of Salem, to Give the Alarm.“

Courtesy Skinner Auctions; note the anachronistic photo inserted on the right.

Courtesy Skinner Auctions; note the anachronistic photo inserted on the right.

“Anniversary History” was alive and well in 1775: Even in the standard reports of Leslie’s Retreat published in the week after, I couldn’t help but notice the juxtaposition of what had just happened in Salem and the imminent fifth anniversary of the Boston Massacre. Side by side we can read of Leslie’s “ridiculous” expedition and “an Oration, in commemoration of the Massacre, perpetuated in King-Street, on the 5th of March, 1770, by Joseph Warren, Esq.” and several reports made the connection between the two, which occurred on successive sabbaths. Dr. Warren actually spoke on March 6, 1775, and I wish he had referenced Salem, but he did not. Nevertheless, you can really feel the drumbeat of rebellion when you read the New England papers published in March of 1775: there are lessons to be learned and anecdotes to be memorialized. The editors of the Newport Mercury were also thinking historically when they opined that as our brave ancestors used to carry their implements of war with them to their places of worship during the Indian wars, perhaps our brethren of the Massachusetts Bay have good reason to make use of the same precaution at this day. I also can’t resist adding another eyewitness testimony here, from a “True Son of Old Ireland” who was on the spot, as well as my very favorite photograph of the First Reenactment of Leslie’s Retreat, two years ago: these guys played their roles really well.

The Newport Mercury of March 6, 1775 and the Essex Gazette of March 7, 1775; Lt. Colonel Leslie (Charlie Newhall!!!) exasperated and outflanked two years ago.

The Newport Mercury of March 6, 1775 and the Essex Gazette of March 7, 1775; Lt. Colonel Leslie (Charlie Newhall!!!) exasperated and outflanked two years ago.

Commemorating Leslie’s Retreat on February 24: Reenactment at 11:15-11:30 for Redcoats (meet at Hamilton Hall) and Patriots (meet at the First Church). Reception afterwards at First Church.

A Staged Reading of Endicott’s Leslie’s Retreat at the Pickering House by Keith Trickett, 3pm: https://pickeringhouse.org/events/special-leslies-retreat-performance/.

Toast the Retreat and Salem’s Resistance at O’Neill’s Pub on Washington Street from 4-7pm.

And coming in April: the Resistance Ball at Hamilton Hall: https://www.hamiltonhall.org/full-event-calendar/2019/2/1/resistance-ball

Like this:

Like Loading...

The Salem Courthouse from Massachusetts Magazine, 1790 and Smithsonian Library Collections; I dropped “General Gage” into his drawing room at the Hooper Mansion, photograph from the Nelson-Atkins Museum.

The Salem Courthouse from Massachusetts Magazine, 1790 and Smithsonian Library Collections; I dropped “General Gage” into his drawing room at the Hooper Mansion, photograph from the Nelson-Atkins Museum.

I am not showing you Major Pedrick because he should not have been there!

I am not showing you Major Pedrick because he should not have been there!