So you would think that I would be happy when an exhibition of paintings, texts and objects right in my teaching sweet spot of late Medieval/Renaissance/Reformation/Early Modern Europe comes to my very own city, and yes, I am. Have I taken advantage of said exhibition and brought my students to see things which I regularly refer to? No I have not. The “Saints & Sinners” in my post title refers to the current exhibition at the Peabody Essex Museum, Saints, Sinners, Lovers, and Fools: 300 Years of Flemish Masterworks, and the “Bad Professor” is me. This has happened before: the PEM has a global purview, and several exhibits which have complemented my courses have been up, but this one is really spot on. So when I finally went yesterday afternoon (it opened in December and is up until May), I really enjoyed it, but also felt bad. I am really not good at out-of-the-classroom activities with my students: I never have been and I never had to be. All my colleagues are a lot better. I always used to think, oh well, they’re Americanists, it’s easy for them, but that’s not going to work in this case is it? And I’ve always blamed it on Salem State’s location—about a mile out of downtown Salem. It’s not very far, but it feels far, when you’re trying to cover so much in the limited time of a semester. I walk it often, but to and from is going to eat up an entire class with not much time for viewing in between. The original Salem State (Salem Normal School) was located just behind my house on Broad Street, but in the 1890s there was a big move to a more expansive—now residential—area south. The move made sense at that time, but now I think our university would benefit from a downtown location, or maybe I’m just making excuses! I have occasionally invited my students to join me at exhibitions, and a few have, but never the entire class: my students seem very busy, taking six classes and working two jobs—oops, more excuses. In any case, I’m certainly going to extend that offer to them for this exhibition, because they will in fact see many things which they have heard about before.

Detail from Jan Wildens, Panoramic View of the City of Antwerp across the River Scheldt, 1630.

Detail from Jan Wildens, Panoramic View of the City of Antwerp across the River Scheldt, 1630.

Saints and Sinners is a traveling exhibition co-organized by the Denver Art Museum and the Phoebus Foundation in Antwerp, and it is very Antwerp-centric. Once certainly gets a sense of the somewhat wider world that was late medieval and Renaissance Flanders, but Antwerp is the star of the show. But that’s ok, because Antwerp was a very dynamic city in this era–the first non-Italian European entrepot. [a great read for the non-specialist is Michael Pie’s Europe’s Babylon: the Rise and Fall of Antwerp’s Golden Age] The exhibition opens with two galleries exploring intense late medieval piety and the rise of Christian humanism in northern Europe: there wasn’t much discussion in the exhibition text about the latter (or humanism in general, really) but I saw it all around me in both the Christocentric devotion and the subtle critique of the Church, most evident in Anthony Rebukes Archbishop Simon de Sully in Bourges, (c. 1475, by Master of the Prado Adoration). There is a lovely little triptych with a nice interpretive feature.

Circle of Dirk Bouts, The Virgin and Child in an Enclosed Garden , about 1468; Master of the Prado Adoration, Anthony Rebukes Archbishop Simon de Sully in Bourges, about 1475; Artist in the Southern Netherlands, Triptych with Saint Luke Painting the Virgin Mary and Jesus, 1520-30.

Then we were on to more worldly things: shockingly fresh portraits of people who were not saints, still-lives of stuff, a few landscapes, battle scenes, scenes of daily life and satire, cabinets of curiosities. The segue between the spiritual and material worlds was a succession of Adoration of the Magi paintings, focusing on stuff. You can never underestimate the impact of the Renaissance portrait, and I was particularly wowed by the portrait of Joost Aemsz. van der Burch by Jan van Scorel. He looks very (Thomas) Cromwellian to me, and yes, he was a contemporary and also a legal advisor, to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. I love portraits of the new nobility of merit or robe (rather than the sword) and also of merchants, the other new men of the era. One of the most captivating (double) portraits of this exhibition is the rather pointed portrait of two “tax collectors,” a copy of the famous Quentin Massys painting of the same title. This image is a great teaching tool: I suspect the men were in fact “tax farmers,” collecting taxes for the government for a certain percentage, a practice which emerged before the expansion of professional state fiscal agencies, and their depiction conveys a lot about attitudes towards money, class, occupation, society, and even color. Another double portrait of a married couple was also interesting: they are obviously well-heeled and playing “triktrak,” an early form of backgammon.

Quinten Massys, Tax Collectors, late 1520s, oil on panel, 86 x 71 cm. Liechtenstein Collection, Vaduz/ Vienna.

LOVE this first portrait above: Jan van Sorel, Portrait of Joost Aemsz. van der Burch, 1530-1; Marinus von Reymerswaele, After Quinten Metskis, Tax Collections, about 1530;

I was familiar with most of the printed texts in the exhibitions but the key reference works were there: the very important and popular Cosmographia of Petrus Apianus, the pioneering On the Fabric of the Human Body by Andreas Vesalius, and the Nova Reperta engravings by Flemish artist Johannes Stradanus published by Philips Galle. The Nova Reperta (New Intentions of Modern Times) is a portfolio of 19 European “inventions” (many of which are not inventions and certainly not European inventions) is such a testament to European pride (and invention!) at the end of the very dynamic sixteenth century. The frontispiece alone is revealing [I use this great digital site at the Newberry Library in class]: highlighted are 1) the western hemisphere (ok Europe gets credit for that discovery), the printing press (Chinese origin–I don’t see the type here!), distillation (I would call this a Eurasian collaboration), wood from the guiacum tree in Brazil (then thought of as the cure to another American import, syphillis, but soon to be abandoned for mercury), a cannon (ok the Europeans encased Chinese gunpowder), a saddle with stirrups (ancient!), a clock (clock history is complicated but if we’re talking mechanical I think I will give it to Europe). As the exhibit moved into a surreal and satirical gallery, with a Bosch-esque Hell, and lots of foolery, I was with it, but I walked right through the boring Classical Impact section (not what I’m looking for in Antwerp) into the galleries of wonder and cabinets of curiosity. It was fun to see actual Wunderkammer as well as paintings of wealthy Flemish men and women with their collections of exotic objects and paintings; one can easily grasp how connoisseurship expanded into collecting and it was almost as if these galleries were a mirror of the entire exhibition.

Andreas Vesalius, On the Fabric of the Human Body in Seven Books, 1543; Follower of Hieronymus Bosch, detail from Hell, 1540-5-; Daniel Teniers, Festival of Monkeys, 1633; Gillis van Tilborgh II, Twelve Gentlemen in an Elegant Interior, about 1661; The Famous Pocupine in London, 1672 @Trustees of the British Museum. After I saw him in the bottom right corner of the Cabinet in the exhibition, I had to put in him here as he is my favorite early modern porcupine.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Artist in the United States, Portrait of Lieutenant Benjamin West, 1774-1775. Pastel on paper. Gift of Mrs. Sarah C. Bacheller, 1922. 116640. Peabody Essex Museum.

Artist in the United States, Portrait of Lieutenant Benjamin West, 1774-1775. Pastel on paper. Gift of Mrs. Sarah C. Bacheller, 1922. 116640. Peabody Essex Museum.

Detail from Jan Wildens, Panoramic View of the City of Antwerp across the River Scheldt, 1630.

Detail from Jan Wildens, Panoramic View of the City of Antwerp across the River Scheldt, 1630.

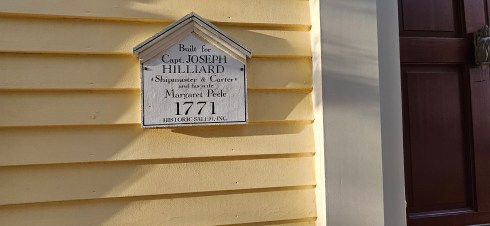

random scenes on my way and back; don’t drive to Salem!

random scenes on my way and back; don’t drive to Salem!

Gardner-Pingree, Crowninshield-Bentley, Derby-Beebe summerhouse, John Ward, and Andrew Safford houses of the Peabody Essex Museum.

Gardner-Pingree, Crowninshield-Bentley, Derby-Beebe summerhouse, John Ward, and Andrew Safford houses of the Peabody Essex Museum.

Peirce-Nichols house and Ropes Mansion garden–now in full bloom.

Peirce-Nichols house and Ropes Mansion garden–now in full bloom.

back to work: one good thing about October is I can’t find excuses not to walk to work, along Lafayette Street where there is a range of “decorations”. I like these little skeletons.

back to work: one good thing about October is I can’t find excuses not to walk to work, along Lafayette Street where there is a range of “decorations”. I like these little skeletons.

Joseph Howard, watercolor of the Essex, after 1799, Peabody Essex Museum.

Joseph Howard, watercolor of the Essex, after 1799, Peabody Essex Museum. Maps from Philip Chadwick Foster Smith’s The Frigate Essex Papers.

Maps from Philip Chadwick Foster Smith’s The Frigate Essex Papers.

Plans and photos of the Ezekiel Hersey Derby House, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum; the Derby Room at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Plans and photos of the Ezekiel Hersey Derby House, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum; the Derby Room at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Building in 1779-1780: now that’s confidence. Elias Hasket and Derby began construction on Salem’s Maritime’s

Building in 1779-1780: now that’s confidence. Elias Hasket and Derby began construction on Salem’s Maritime’s