This has been such a “revolutionary” year for me; I had to cap it off by an actual event: the reenactment of the raids on Fort William and Mary in New Castle, New Hampshire on December 14 and 15, 1774 this past weekend. There were two raids on this under-manned fort: first they came for the gunpowder, then for the cannon. From September of 1774 New England had been in a constant state of alarm: these December actions were the first overt revolutionary actions: if the Fort had actually been manned, I do believe the American Revolution would have begun in December of 1774 rather than April of 1775. “What if” history is generally pointless, but still, this particular episode has everything: a mid-day ride by Paul Revere warning the people of Portsmouth of the imminent arrival of warships, two raids on successive days, removing the “peoples’s” gunpowder and cannon from the “king’s” fort, a trampled British flag.

I was early for the December 15 reenactment, so I walked around a nearly people-less New Castle with bells ringing on Sunday morning: despite the calm, it was kind of exciting!

You can read that I am using the language from the official marker: “overt”. It was overt! It was open treason after Revere arrived in Portsmouth in the late afternoon of December 13. One of the town’s wealthiest and most influential residents, John Langdon (Continental Congress member and later President pro tempore of the US Senate and Governor of New Hampshire), recruited Patriot raiders on the streets with fife and drum, and eventually a force of nearly 400 militiamen assaulted the Fort on the next day. Inside were a mere five men under the command of Captain John Cochran, who gave this account to the Royal Governor John Wentworth: About three o’ clock the Fort was besieged on all sides by upwards of four hundred men. I told them on their peril not to enter; they replied they would; I immediately ordered three four-pounders to be fired on them, and then the small arms, and before we could be ready to fire again, we were stormed on all quarters, and they immediately secured both me, and my men, and kept us prisoners about one hour and a half, during which time they broke open the Powder House, and took all the Powder away except one barrel, and having put it into boats and sent it off, they released me from my confinement. Despite the fire, there were no injuries, except for the Fort’s flag, which was pulled down and trampled upon. About 100 barrels of gunpowder were dispensed to nearby towns for safekeeping.

Howard Pyle’s illustration of the Surrender of Fort William and Mary, December 14, 1774, New York Public Library Digital Gallery.

And on the next day they came back for the cannon. Even more men, from both sides of the Piscataqua (the Maine side was then Massachusetts), under the command of Continental Congress member John Sullivan (another Continental Congress representative and future NH governor), raided the surrendered fort and carried away 16 cannon, 60 muskets and additional military stores. Sullivan had formerly been close friends with Governor Wentworth, but their relationship was severed by the latter’s Loyalism and lies to his countrymen, a point that was played up by the reenacting Sullivan in his speech to his troops and audience. I think they were planning to return to the pillaged port again but were preventing from doing so by the arrival of two British ships, the Canceaux and the Scarborough in the following week.

After a rousing speech by Sullivan (2024), off to the Fort!

Reenactors (and reenectment attendees) often endure extreme heat and cold waiting for reenactments to occur! It was a cold morning, but as you can see by this charming reenactor’s smile, also a pleasurable one. I was so whipped up by Sullivan’s (2024) speech that I felt that I had to visit Governor Wentworth’s nearby house, as if expecting to find him there to counter his former friend’s accusations. I will give him not the last word but a last word, as I think we need some more contemporary accounts: the letter from Portsmouth below was featured in all the American newspapers in the last week of December, and then Governor Wentworth’s proclamation followed in early January of 1775. The separation seems severe.

Essex Gazette, January 10, 1775.

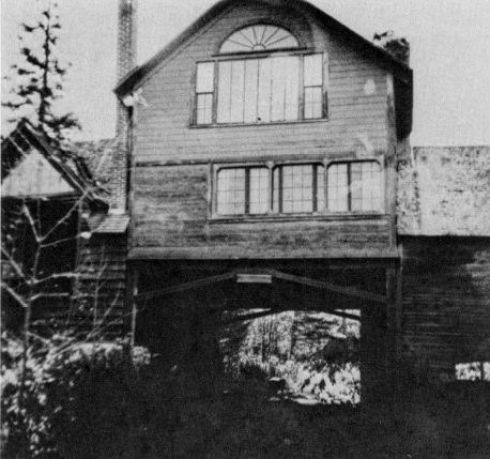

The Hearse House in Marlow, New Hampshire.

The Hearse House in Marlow, New Hampshire.

The McDermott Covered Bridge in Langdon (1864); the Meriden Bridge in Plainfield (1880); the Cilleyville (or Bog) Bridge in Andover (1887); the Keniston Bridge, also in Andover (1882); just two of Cornish’s FOUR covered bridges: somehow I missed the “Blow Me Down” Bridge and the Cornish-Windsor Bridge over the Connecticut River is

The McDermott Covered Bridge in Langdon (1864); the Meriden Bridge in Plainfield (1880); the Cilleyville (or Bog) Bridge in Andover (1887); the Keniston Bridge, also in Andover (1882); just two of Cornish’s FOUR covered bridges: somehow I missed the “Blow Me Down” Bridge and the Cornish-Windsor Bridge over the Connecticut River is

Salisbury & Fremont, New Hampshire.

Salisbury & Fremont, New Hampshire. Salem Register, August 19, 1841.

Salem Register, August 19, 1841.

The Rundlet-May House (1807) and views out back from its second and third floors.

The Rundlet-May House (1807) and views out back from its second and third floors.

First-floor parlors, hall and kitchen (with Rumford Roaster) and fire buckets, of course. I found several early 20th-century postcards of the house which referred to Samuel McIntire as the carver of the right parlor’s mantle (above), but I think this is just an illustration of the Salem architect and woodcarver’s fame in the midst of the Colonial Revival era.

First-floor parlors, hall and kitchen (with Rumford Roaster) and fire buckets, of course. I found several early 20th-century postcards of the house which referred to Samuel McIntire as the carver of the right parlor’s mantle (above), but I think this is just an illustration of the Salem architect and woodcarver’s fame in the midst of the Colonial Revival era.

Second and Third Floors, including Ralph May’s 3rd floor study, with all of his stuff. Below: this “musical” decorative motif ran through the house—it caught my eye because the same motif is on one of my Fancy chairs. (the last photograph).

Second and Third Floors, including Ralph May’s 3rd floor study, with all of his stuff. Below: this “musical” decorative motif ran through the house—it caught my eye because the same motif is on one of my Fancy chairs. (the last photograph).

Palpitations.

Palpitations.

Can you believe this amazing DOUBLE HOUSE!!!!!!

Can you believe this amazing DOUBLE HOUSE!!!!!!

Historical markers are everywhere in New Hampshire—and Salem’s Massachusetts Tercentenary markers are still among the missing; a Sunday afternoon exhibit/gathering at Hancock’s Historical Society.

Historical markers are everywhere in New Hampshire—and Salem’s Massachusetts Tercentenary markers are still among the missing; a Sunday afternoon exhibit/gathering at Hancock’s Historical Society.

The 101st Field Artillery in France, and just three of Salem’s World War I Memorials.

The 101st Field Artillery in France, and just three of Salem’s World War I Memorials.

Fernlea, early morning: designed by Russell Sturgis for Miss Mary Amory Greene, 1882-1883.

Fernlea, early morning: designed by Russell Sturgis for Miss Mary Amory Greene, 1882-1883.

The Thayer cottage complex and studio, and Gladys Thayer (Abbott’s daughter) in her sleeping hut, circa 1900. Nancy Douglas Bowditch and Brush Family papers, circa 1860-1985, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution: cited in Susan Hobbs, “Nature into Art: the Landscapes of Abbott Handerson Thayer”, The Journal of American Art 14 (Summer 1982): 4-55.

The Thayer cottage complex and studio, and Gladys Thayer (Abbott’s daughter) in her sleeping hut, circa 1900. Nancy Douglas Bowditch and Brush Family papers, circa 1860-1985, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution: cited in Susan Hobbs, “Nature into Art: the Landscapes of Abbott Handerson Thayer”, The Journal of American Art 14 (Summer 1982): 4-55.

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Dublin Pond, New Hampshire, 1894, Smithsonian American Art Museum (painted as a gift for Stanford White); my early-morning view across from Fernlea; An Angel, 1903, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Dublin Pond, New Hampshire, 1894, Smithsonian American Art Museum (painted as a gift for Stanford White); my early-morning view across from Fernlea; An Angel, 1903, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.