I am still processing Winterthur, so this is a rather premature post, but I wanted to get my first impressions and thoughts out there and sometimes posting is processing! It was just so wonderful, in so many ways, especially as my friends and I toured its many period rooms in the company of Wendy A. Cooper, Curator Emerita of Furniture and conservator Christine Thomson. If the majesty of the rooms and their furnishings was not enough, the commentary of these two brilliant women on style, detail, condition, context, and provenance provided a soundtrack of sorts which enhanced the whole experience. And we got to go where more scheduled tours could not–which is always fun: if we did not make it through Winterthur’s 175 rooms, we came pretty close, and by the time of the closing bell we were on the top floor. While Ms. Cooper’s specialty is furniture, she seemed to have a mastery of every object in every room, as well as the history of Winterthur itself, so the takeaway was a very personal, even intimate, view of both the museum, its collections, and its founder, Henry (Harry) Francis du Pont (1880-1969). During our tour, I was so focused on absorbing every little detail that I didn’t really process, but afterwards, and all this week, I kept comparing Winterthur to another famous house museum, across the pond: Sir John Soane’s Museum. I needed context, I needed a comparison, and while I know that Winterthur is comprised of parts of many different houses and inspired more by the tradition of installing period rooms that started right here in Salem with George Francis Dow’s exhibits at the Essex Institute and Soane’s (much smaller) house is uniquely his place and collection, and fixed at a more exact point in time, the two houses seem both stuffed and the stuff of very personal passions for collecting: materialistic rather than “scientific” wunderkammers.

Port Royal Parlor at Winterthur and South Drawing Room at Sir John Soane’s Museum, photograph by Derry More.

Port Royal Parlor at Winterthur and South Drawing Room at Sir John Soane’s Museum, photograph by Derry More.

The personal was my window into Winterthur: somehow stories of Mr. du Pont entertaining antique dealers over dinner and then proceeding to invite them to help rearrange the furniture reminded me of the more eccentric Mr. Soane. As I did when I first visited the London museum, I really felt the stamp of Mr. du Pont on Winterthur: period rooms can be rather cold, detached places (as they are literally detached), but Winterthur felt warm. The big, showy parlors and dining rooms of the main floors less so than the upper stories, but still, altogether an inviting installation—impressive for a museum of such scale.

So many rooms—and stuff—for eating and drinking, of course, but dining rooms can be very revealing in their details. After the famous Chinese Parlor are several shots of the Du Pont Dining Room, with the Derby family’s green knives and knife boxes (+ McIntire chairs and Needham secretary, and adjacent candlestick closet. I can’t remember the name of the second, simple dining room, which is one of my favorite Winterthur rooms, but the photograph just above is of Queen Anne Dining Room, which really represents Mr. du Pont’s creative abilities (as well as his collecting efforts).

So many rooms—and stuff—for eating and drinking, of course, but dining rooms can be very revealing in their details. After the famous Chinese Parlor are several shots of the Du Pont Dining Room, with the Derby family’s green knives and knife boxes (+ McIntire chairs and Needham secretary, and adjacent candlestick closet. I can’t remember the name of the second, simple dining room, which is one of my favorite Winterthur rooms, but the photograph just above is of Queen Anne Dining Room, which really represents Mr. du Pont’s creative abilities (as well as his collecting efforts).

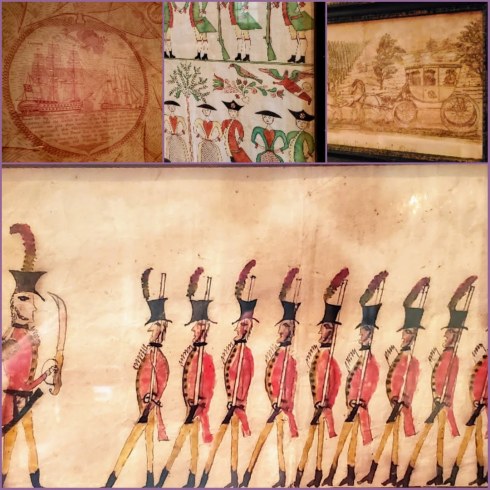

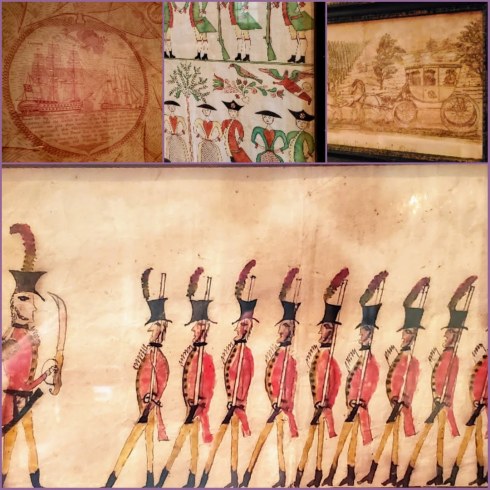

Some more observations and thoughts not yet fully developed, impressions: you really have to put your New England preferences aside and pay tribute to Philadelphia and New York furniture when you visit Winterthur (particularly the former, wow), but Mr. du Pont seems to have been just as passionate a collector of American (or should I say eastern American) folk art as high-style furniture. I knew I could get pictures of the grand rooms from the Winterthur website (plus they have a great digital database) so I took pictures of lots of little things that caught my eye (see some below). How many eagles are there in Winterthur? They seemed to be everywhere. And tea tables! Apparently Mr. du Pont’s collections started with pink transferware and he continued to assemble pottery collections with great conviction: there are several rooms devoted entirely to a variety of wares, even spatterware. And yes, parochial person that I am, I did seek out Salem items, which were not hard to find: there’s a whole room dedicated to McIntire, and other pieces scattered around. In just one room, of painted furniture pretty high up, Ms. Cooper casually pointed out a lovely silk chimneypiece embroidered by Sarah Derby Gardner and a Silsbee chair. The Du Pont Dining Room (above) featured not only knives from the Derby family, but also some McIntire side chairs, and an amazing secretary/bookcase made by Nehemiah Adams. In his own suite of rooms, Mr. du Pont worked on another Salem secretary, with a Nathaniel Gould chest of drawers nearby. An entire room is wallpapered with a mural painted by Michel Felice Corné for the Lindall-Barnard-Andrews House at 393 Essex Street in Salem.

The Montmorenci stair, taken from a North Carolina house, replaced the “baronial” staircase which Mr. du Pont’s father installed. Folk objects and images, just a few tea tables, and just one china room. Several Salem items: the chimneypiece embroidered by Sarah Derby Gardner, a Silsbee chair, Mr. du Pont’s secretary (and bed), and the Corné mural from the Lindall-Barnard-Andrews House.

The Montmorenci stair, taken from a North Carolina house, replaced the “baronial” staircase which Mr. du Pont’s father installed. Folk objects and images, just a few tea tables, and just one china room. Several Salem items: the chimneypiece embroidered by Sarah Derby Gardner, a Silsbee chair, Mr. du Pont’s secretary (and bed), and the Corné mural from the Lindall-Barnard-Andrews House.

I could go on and on and on, but I’m going to wrap it up with just a few more of my favorite things/rooms, in no particular order. I really loved the William and Mary Parlor, pretty much every image of George Washington (and there were many), the detail on an otherwise simple chest of drawers, two pastels by John Singleton Copley of himself and his wife (and the amazing high-style parlor which they overlook), a very early billiards table, and an elegant curved settee for which Mr. du Pont built a wall. And just to bring in a touch of a real wunderkammer, a wonderful little anatomical plate.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Some of the larger Victorians on Church Street (just above) need some help, but just up the hill is a lovely neighborhood of mostly-restored structures. Below: the Arnold Print Works produced a full line of textiles over their long history, but one of their popular products in the 1890s were these stuffed animal templates (examples below from the collections of the Rhode Island School of Design Museum & Cooper Hewitt): the finished products are very collectible and you can buy reproductions too (here are some Etsy examples).

Some of the larger Victorians on Church Street (just above) need some help, but just up the hill is a lovely neighborhood of mostly-restored structures. Below: the Arnold Print Works produced a full line of textiles over their long history, but one of their popular products in the 1890s were these stuffed animal templates (examples below from the collections of the Rhode Island School of Design Museum & Cooper Hewitt): the finished products are very collectible and you can buy reproductions too (here are some Etsy examples).

Port Royal Parlor at Winterthur and South Drawing Room at Sir John Soane’s Museum, photograph by Derry More.

Port Royal Parlor at Winterthur and South Drawing Room at Sir John Soane’s Museum, photograph by Derry More.

So many rooms—and stuff—for eating and drinking, of course, but dining rooms can be very revealing in their details. After the famous Chinese Parlor are several shots of the Du Pont Dining Room, with the Derby family’s green knives and knife boxes (+ McIntire chairs and Needham secretary, and adjacent candlestick closet. I can’t remember the name of the second, simple dining room, which is one of my favorite Winterthur rooms, but the photograph just above is of Queen Anne Dining Room, which really represents Mr. du Pont’s creative abilities (as well as his collecting efforts).

So many rooms—and stuff—for eating and drinking, of course, but dining rooms can be very revealing in their details. After the famous Chinese Parlor are several shots of the Du Pont Dining Room, with the Derby family’s green knives and knife boxes (+ McIntire chairs and Needham secretary, and adjacent candlestick closet. I can’t remember the name of the second, simple dining room, which is one of my favorite Winterthur rooms, but the photograph just above is of Queen Anne Dining Room, which really represents Mr. du Pont’s creative abilities (as well as his collecting efforts).

The Montmorenci stair, taken from a North Carolina house, replaced the “baronial” staircase which Mr. du Pont’s father installed. Folk objects and images, just a few tea tables, and just one china room. Several Salem items: the chimneypiece embroidered by Sarah Derby Gardner, a Silsbee chair, Mr. du Pont’s secretary (and bed), and the Corné mural from the Lindall-Barnard-Andrews House.

The Montmorenci stair, taken from a North Carolina house, replaced the “baronial” staircase which Mr. du Pont’s father installed. Folk objects and images, just a few tea tables, and just one china room. Several Salem items: the chimneypiece embroidered by Sarah Derby Gardner, a Silsbee chair, Mr. du Pont’s secretary (and bed), and the Corné mural from the Lindall-Barnard-Andrews House.

Longwood Gardens + Conservatory and “Green Wall” surrounding restroom doors!

Longwood Gardens + Conservatory and “Green Wall” surrounding restroom doors!

Treasures of the Brandywine River Museum of Art, including: Howard Pyle’s influential “historic” illustrations and a N.C. Wyeth cover, Andrew Wyeth’s Snow Hill and Jamie Wyeth’s Lime Bag, N.C.’s studio exterior and interior and in Andrew’s North Light, N.C. Wyeth, framed by his parents and looking down on his talented family, a Jamie Wyeth Christmas card for his beloved wife Phyllis.

Treasures of the Brandywine River Museum of Art, including: Howard Pyle’s influential “historic” illustrations and a N.C. Wyeth cover, Andrew Wyeth’s Snow Hill and Jamie Wyeth’s Lime Bag, N.C.’s studio exterior and interior and in Andrew’s North Light, N.C. Wyeth, framed by his parents and looking down on his talented family, a Jamie Wyeth Christmas card for his beloved wife Phyllis.

The arch of the Praça do Comércio, the Square of Commerce, is the proper entry to Lisbon, from the sea, but it’s a nineteenth-century construction after the rebuilding of the square following the earthquake of 1755. A great mural in the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga shows the pre-1755 square. The Church of

The arch of the Praça do Comércio, the Square of Commerce, is the proper entry to Lisbon, from the sea, but it’s a nineteenth-century construction after the rebuilding of the square following the earthquake of 1755. A great mural in the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga shows the pre-1755 square. The Church of

I’m trying to show the integration and proximity of new and old with these pictures, which include several streetscapes, views from the Castelo de S. Jorge, the Church of

I’m trying to show the integration and proximity of new and old with these pictures, which include several streetscapes, views from the Castelo de S. Jorge, the Church of

Belem: site of the iconic Manueline

Belem: site of the iconic Manueline

Museums: so many! History museums and museums of every conceivable form of art: “ancient” (pre-1850), modern, decorative, TILES, marionettes. The famous Gulbenkian collection and several less well-known house museums: I was blown away by the

Museums: so many! History museums and museums of every conceivable form of art: “ancient” (pre-1850), modern, decorative, TILES, marionettes. The famous Gulbenkian collection and several less well-known house museums: I was blown away by the

Horses and ballet slippers (a nod to the New York City Ballet’s summer residence at the Saratoga Performing Arts

Horses and ballet slippers (a nod to the New York City Ballet’s summer residence at the Saratoga Performing Arts

The Gideon Tucker Doorway and House (1804): Frank Cousins photographs from the 1890s; the Brickbuilder, January 1924; New York Public Library Digital Gallery, n.d.; Essex Institute postcard, MACRIS (1979) and present.

The Gideon Tucker Doorway and House (1804): Frank Cousins photographs from the 1890s; the Brickbuilder, January 1924; New York Public Library Digital Gallery, n.d.; Essex Institute postcard, MACRIS (1979) and present. “Eh bien, Messieurs! deux millions”: Napoleon displaying the treasures of Italy—in France, 1797, Library of Congress.

“Eh bien, Messieurs! deux millions”: Napoleon displaying the treasures of Italy—in France, 1797, Library of Congress.

Historical markers are everywhere in New Hampshire—and Salem’s Massachusetts Tercentenary markers are still among the missing; a Sunday afternoon exhibit/gathering at Hancock’s Historical Society.

Historical markers are everywhere in New Hampshire—and Salem’s Massachusetts Tercentenary markers are still among the missing; a Sunday afternoon exhibit/gathering at Hancock’s Historical Society.

The 101st Field Artillery in France, and just three of Salem’s World War I Memorials.

The 101st Field Artillery in France, and just three of Salem’s World War I Memorials.

The Sheffield Patent, 1623, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum; Title page of Thomas Maule’s New England Pesecutors Mauld, 1697;

The Sheffield Patent, 1623, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum; Title page of Thomas Maule’s New England Pesecutors Mauld, 1697;

A Newsham Engine of similar vintage @Colonial Williamsburg.

A Newsham Engine of similar vintage @Colonial Williamsburg.

Robert Newall photograph of the William Penn Hose Company in Philadelphia with their steam engines, 1865, The Library Company; Harper’s Weekly photograph of the Union, “the oldest fire-engine in the United States” in 1866; a photograph of the Union in an article announcing its return to Salem in The American City, January 1918.

Robert Newall photograph of the William Penn Hose Company in Philadelphia with their steam engines, 1865, The Library Company; Harper’s Weekly photograph of the Union, “the oldest fire-engine in the United States” in 1866; a photograph of the Union in an article announcing its return to Salem in The American City, January 1918.

The Union and some fire buckets were featured prominently in a 1978 Essex Institute booklet: Museum Collections of the Essex Institute by Huldah Smith Payson, and fortunately for us, one of those very same buckets is one of the PEM’s online

The Union and some fire buckets were featured prominently in a 1978 Essex Institute booklet: Museum Collections of the Essex Institute by Huldah Smith Payson, and fortunately for us, one of those very same buckets is one of the PEM’s online

Stills and scenes of Detroit past and present in

Stills and scenes of Detroit past and present in

Scenes from

Scenes from