Last week I was thinking about all the things that annoy or concern me about Salem now, and the list seemed endless, which depressed me, and then I suddenly thought, why don’t I focus on the things that I love about Salem so I won’t be so depressed? This seemed like a good idea, and an easy realignment. Why did I move to Salem? Architecture. What do I love about Salem? Architecture. So I’m going to go back to the foundations of my own Salem story and getting back to architecture with an occasional series here and on social media (#salemhistoryhouses) looking at individual houses in the present and past as a means of telling more Salem stories. Just one house can open a wide window into the city’s history, American history, even world history, as Salem has always had a global orientation. This is not a novel observation, but somehow as I pursued a range of Salem topics here and in our forthcoming book Salem’s Centuries I lost sight of one of the most basic expressions of cultural achievement: houses. Besides the inspiration of merely pursuing my own happiness, I am also motivated by the efforts of two people who I’ve written about a lot here and also in Salem’s Centuries: Frank Cousins and Mary Harrod Northend. These two contemporaries dedicated a good part of their lives to highlighting Salem architecture in print and image. Both wrote books and magazine articles and established photographic publishing companies which distributed images of Salem houses nationwide. They were both particularly keen to emphasize that all not was lost with the Great Salem Fire of 1914, and that much of Salem’s architectural heritage remained; a decade later both were intent on celebrating that heritage during Salem’s Tercentenary in 1926. Cousins died the year before; Northend in that very year. I’ll feature a lot of their work in my series, as preserved and digitized by the Phillips Library (via Digital Commonwealth), the Winterthur Library, and Historic New England, as well as the large collection of images available at the Salem State University Archives and Special Collections. So there you are, or there I am: one of the things that annoys me about Salem is its lack of a professional historical museum, but all these institutions, and more, are in fact collecting, preserving, and sharing Salem history.

My first social media post is a great example of how just one house can lead you in all sorts of directions. The Eden-Browne has was built in 1762 by Captain Thomas Eden as a warehouse, and then converted into a (very elegant) residence by Benjamin Cox in 1834. Captain Eden was a trader in the codfish rectangular trade between Salem, southern Europe, and the West Indies, and the very first member of the Salem Marine Society: his grandaughter, the artist Sarah Eden Smith, lived and died in the house. Her other grandfather, Jesse Smith, was an officer in General Washington’s First Horse Guards, and she herself was a professional artist and instructor who spent several years at the Hampton Institute (now University) teaching Native American students. Miss Smith, “the last of her family,” was also the author of a lovely little pamphlet on the history of the Second Church of Salem, visible below in the top photograph, which obviously dates from before it was demolished by fire in 1903. So that’s a lot of history tied to just one Salem house!

A house that both Cousins and Northend adored (both really seem to have preferred Salem’s 18th-century houses) is the Dean-Sprague-Stearns House on the corner of Essex and Flint Streets. It was built in 1706 and acquired a portico by Samuel McIntire a century later. It has a connection to Salem’s most notable Revolutionary event, Leslie’s Retreat, through the residence of distiller Joseph Sprague, a major participant in that resistance, and it was operated as an inn named the East India House in the middle decades of the twentieth century. I love the description of this house in Samuel Chamberlain’s Open House in New England: “the EAST INDIA HOUSE contains a wig room, two powder rooms and a Tory hide-out in one of the chimneys. A quadrille was given here for General Lafayette in 1824.” TORY HIDE-OUT.

Top photograph from the Frank Cousins Collection of Glass Plate Negatives at the Phillips Library, via Digital Commonwealth.

Talk about going back to Salem houses: One Forrester Street was one of the first house reports I researched and wrote for Historic Salem, Inc., way back in the 1990s! I was in graduate school, and this was my way of “learning” Salem. These are another great resource (and mine are far from the best!), as members of the Salem Historical Society digitized them several years ago. These house histories, in addition to the Massachusetts Historical Commission’s MACRIS database, represent accessible information about hundreds of Salem houses. I remember being very excited about researching One Forrester as it’s such a great house, with a distinctive profile right on Salem Common. Though built by a tanner named John Ives, the house was kept in the Webb family for quite some time, I think, almost two centuries. In the northwest corner of the house is a “cent shop” straight out of the House of the Seven Gables; it might even have been Hawthorne’s inspiration.

Stereoview (top) from the 1860s, and the Nelson Dionne Salem History Collection at Salem State University.

There were many Webbs in Salem and it is quite a challenge to keep them straight! Sea captains in the 18th century, entrepreneurs in the nineteenth. Another Webb house is one of my favorite brick-sided houses in Salem, adjacent to what was long a Webb apothecary shop on Essex Street. These buildings are 52 (house) and 54 (shop) Essex Street, and they represent what were probably hundreds of attached or adjacent residences and shops which once existed in Salem.

Stereoview from the Dionne Salem History Collection, Salem State University Archives and Special Collections.

I’ve decided that I’m not going to feature lost houses in my little series, as I am engaged in the pursuit of happiness. But I’m definitely going to feature houses that were moved, because there are so many, and also because I love these examples of nineteenth-century (and a bit of twentieth-century) sustainability. One house that was moved from Salem’s main street, Essex, to a nearby side street is Five Curtis Street, which is featured prominently in one of my favorite architecture books, John Mead Howells’ Lost Examples of Colonial Architecture: Buildings That Have Disappeared of Been so Altered as to be Denatured: Public Buildings,Semi-Public Churches, Cottages, Country Houses, Town Houses, Interiors, Details (1931). It is indeed one of my favorite books, but I also realize that Howells makes a lot of mistakes, so I always check him. He indicates that the house was moved in 1895, which does check out, and refers to the house as the Joseph J. Knapp House. More recent researchers refer to the house as the the John White House, and I think this is correct: White, a mariner, built the house around 1802 and sold it to Knapp, another mariner (a loose term which generally means merchant and maybe captain but more likely owner of shares in a ship at that time) six years later. The house remained in the Knapp family until 1848, which means that this house has a connection to the most notorious murder in nineteenth- century Salem. Joseph J. Knapp’s two sons, John Francis (Frank) and Joseph Jenkins Jr., hired Richard Crowninshield to murder their wealthy uncle Captain Joseph White in 1830 and all three met their deaths before the end of that year. Mr. Knapp Sr. had already decamped for Wenham before these events, and he remained there until his death in 1847.

Frank Cousins photograph of the Knapp House in its original location on Essex Street (on the corner of Orange), John Mead Howells, Lost Examples of Colonial Architecture (1931).

Fame AND Authority: Occasionally Mary Harrod Northend would present wistful Wallace Nutting-esque views, but mostly she was all about bringing antique material culture into the modern world; notices in Who’s Who in New England and the Architectural Record, citations in trade catalogs were common from 1915 on.

Fame AND Authority: Occasionally Mary Harrod Northend would present wistful Wallace Nutting-esque views, but mostly she was all about bringing antique material culture into the modern world; notices in Who’s Who in New England and the Architectural Record, citations in trade catalogs were common from 1915 on.

Apparently over 1.5 million people visit Salem each year, with nearly 54% of that number in the month of October: for many of those 800,000 or so (I am severely math-challenged), this ⇑⇑ is historical interpretation.

Apparently over 1.5 million people visit Salem each year, with nearly 54% of that number in the month of October: for many of those 800,000 or so (I am severely math-challenged), this ⇑⇑ is historical interpretation.

Carnival Confusion: a City ordinance against mechanical rides on the Common prohibited the annual carnival there, so it was relocated to the middle of Federal Street, but somehow there are electrical rides on the Common as well. This is all very confusing to me, but a colleague of mine commented that the Federal Street location was ok, as those columns on the Greek Revival courthouse are Egyptian Revival, so the Pharaoh fits right in.

Carnival Confusion: a City ordinance against mechanical rides on the Common prohibited the annual carnival there, so it was relocated to the middle of Federal Street, but somehow there are electrical rides on the Common as well. This is all very confusing to me, but a colleague of mine commented that the Federal Street location was ok, as those columns on the Greek Revival courthouse are Egyptian Revival, so the Pharaoh fits right in. 22 Andrew Street: a beautiful Federal (built 1808) located on a lovely street right off the Common (which will not be the site of a carnival for much longer): looks like its

22 Andrew Street: a beautiful Federal (built 1808) located on a lovely street right off the Common (which will not be the site of a carnival for much longer): looks like its  One Forrester Street is right on the Common—it looks Federal but was actually built in 1770. When I first moved to Salem this was the home of a lovely woman whose family had owned it since the 19th Century. It’s been cherished throughout its history, and is still for

One Forrester Street is right on the Common—it looks Federal but was actually built in 1770. When I first moved to Salem this was the home of a lovely woman whose family had owned it since the 19th Century. It’s been cherished throughout its history, and is still for  The Stephen Daniels House is a first-period house which just came on the

The Stephen Daniels House is a first-period house which just came on the

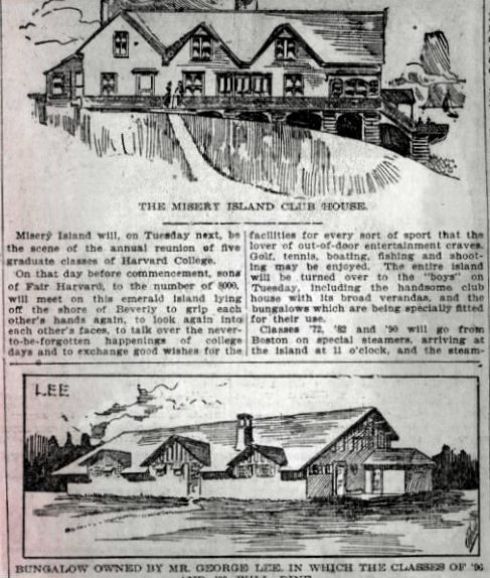

Newspaper reports of the 1902 Harvard reunions (Boston Post, June 22-25, 1902 ) and 1926 fire (Boston Daily Globe, May 8-10, 1926); Great Misery today, and home in Salem Harbor on a glorious early evening!

Newspaper reports of the 1902 Harvard reunions (Boston Post, June 22-25, 1902 ) and 1926 fire (Boston Daily Globe, May 8-10, 1926); Great Misery today, and home in Salem Harbor on a glorious early evening!