This post is about the work of a venerable but new-to-me graphic designer, Seymour Chwast, but before I get to him I have to explain how I got to him. If you have been reading the blog over the past year or so, you might have perceived that I have become mildly obsessed with two images associated with Salem: the official Salem City Seal with its Sumatran trader, now likely on its way out after 180 years or so, and more recently a cartoon cat mascot chosen by the Mayor of Salem and the Salem 400+ Committee to represent our city’s “unique identity” for our upcoming Quadricentennial. The discussion, and in the latter case lack thereof, over both images has been perplexing. I’ve written quite a bit about the seal, and was going to write more about the mascot, but I now realize that such efforts are a waste of time. These images, deemed rascist or representative or not, will stand or fall according to the whims of five or six or maybe 20 people at best. That’s how Salem works: the average person has very little power over matters of civic identity or branding (or anything else for that matter.) Nevertheless, it’s been so interesting exploring the power of images over the past year or so in various ways. As a Renaissance historian, I’ve always been aware of the complexity of images, but if you want to consider their power in the present, that brings you into the realm of graphic design, and so that brought me to Seymour Chwast, briefly. And then he popped into my consciousness again just last week when I was searching for an image of the Battle of Sluys for a powerpoint lecture on the Hundred Years War. The search led to a compelling image of a medieval naval battle which was not Sluys but rather Chwast’s depiction of the Battle of Zonchio in 1499, fought between Venice and the Ottoman Empire. This is just one of nine hand-colored linocut battle scenes, paired with literary quotes on the opposing page, included in Chwast’s 1957 folio A Book of Battles.

Chwast is in his 90s and still working, I think: his career is too prolific and illustrious to summarize here but I will take a stab. Over six decades he has published all sorts of images and illustrations, individually and on behalf of the Push Pin Studios (now Group) the graphic design firm he co-founded in the 1954. From magazine covers to posters to corporate advertising to packaging to theatrical backdrops to his own publications: he has done it all. Chwast is the author of 30 childrens’s books and four graphic novels, and he is also a typeface designer! Chwast’s career is marked by his intent and ability to utilize design as a political force on many occasions, and one theme seems to run through much of his editorial work from the beginning: pacifism. This was certainly the inspiration for his Book of Battles, as the juxtapositions of images and words make clear.

And then, in 2017, a capstone (or maybe not yet) anti-war book, At War with War: 5000 Years of Conquests, Invasions, and Terrorist Attacks. An Illustrated Timeline. More striking graphics and literary excerpts, but a timeline too, which means numbers. The (red) numbers somehow make the illustrations all the more menacing, especially as we proceed into the (modern?) information age in which casualties can be marked along with dates. It all packs a powerful punch.

Still very much in demand: bêche-de-mer at a Hong Kong market, photo by G. Clayden

Still very much in demand: bêche-de-mer at a Hong Kong market, photo by G. Clayden Cokanauto in Charles Wilkes’ United States Exploring Expedition (1845): 3:122.

Cokanauto in Charles Wilkes’ United States Exploring Expedition (1845): 3:122.

The Zotoff (1922 lithograph) and Emerald returning to Salem, (c. 1950 postcard issued by the Salem Chamber of Commerce).

The Zotoff (1922 lithograph) and Emerald returning to Salem, (c. 1950 postcard issued by the Salem Chamber of Commerce). Bure Kalou (Spirit House), Fiji. Peabody Essex Museum. Gift of Joseph Winn Jr., 1835.

Bure Kalou (Spirit House), Fiji. Peabody Essex Museum. Gift of Joseph Winn Jr., 1835.

The second photo above is from the Instagram Account @doorsofsalem where you can see lots more Salem doors.

The second photo above is from the Instagram Account @doorsofsalem where you can see lots more Salem doors.

Illustrations from The old houses and stores with memorabilia relating to them and my father and grandfather / By G. Albert Lewis. The Library Company of Philadelphia.

Illustrations from The old houses and stores with memorabilia relating to them and my father and grandfather / By G. Albert Lewis. The Library Company of Philadelphia.

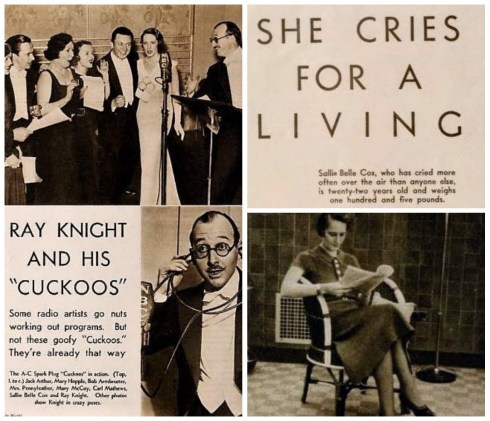

Salem native Raymond Knight and his soon-to-be wife Sallie Belle Cox (behind the microphone at left) in Radio Stars magazine, 1933-34.

Salem native Raymond Knight and his soon-to-be wife Sallie Belle Cox (behind the microphone at left) in Radio Stars magazine, 1933-34.