Walking is my preferred form of transportation in Salem, but I tread carefully: I want my path to be lined with beautiful old houses, colorful shops and lovely green (or white) spaces. Attractions exploiting the terrible tragedy of 1692 and out-of-town-yet-territorial pirates cloud my view and dampen my day. I’m happy to meet real witches and pirates on my walkabouts, but kitschy parodies annoy me. If you are of like mind, there are many routes you can take in Salem on which you will not cross paths with anything remotely touristy, but if you are venturing downtown you must tread carefully too. Avoid the red line at all costs and follow my route below, which I have superimposed on an old map of the so-called “Heritage Trail”: I’m starting at my house on lower Chestnut Street and making a witch-less circle.

Across from my house is Chestnut Street Park: this is not a public park but a private space, owned by all the homeowners of Chestnut Street. It was once the site of two churches in succession: a majestic Samuel McIntire creation which lasted for almost exactly a century and was destroyed by fire in 1903 and a stone replacement which was rather less majestic and lasted about half as long. The gate is usually open to everyone, but not for reseeding time as you can see by the sign. I walk down Cambridge Street by the park and across Essex into the Ropes Mansion Garden, not looking great now but an amazing high summer garden. Then I walk down Federal Court and across Federal Street to the Peirce-Nichols House which is owned, like the Ropes Mansion, by the Peabody Essex Museum. Unlike the Ropes, I can’t remember when the Peirce-Nichols was last opened to the public: it’s been decades. It has a lovely garden in back which was always open, and my favorite place to go at this time of year because of its preponderance of Bleeding Hearts. The gate to the back of the house has been closed for a couple of years now, but it is latched and not locked, so I entered and went into the rear courtyard, passing the memorial stone dedicated to the memory of Anne Farnam, the last director of the Essex Institute before it was absorbed into the Peabody Essex Museum on my right. I never knew Anne but I’ve learned a lot from her articles in the Essex Institute Historical Collections so I always pay tribute. The gate to the garden in back was latched and locked, so I presume the museum does not want us to venture in there. I hope it was ok to go that far! While I am grateful for these pem.org/walks recordings I’m always wondering why these houses are never open.

Continue down Federal Street past the courthouses: you must avoid Lynde Street and Essex Street where witch “attractions” abound. I take a left after Washington street onto a street that no longer exists: Rust Street. I like the juxtaposition of the newish condominiums and the old Church and Bessie Monroe’s brick house on Ash Street on the right: a symbol of the opposition to urban renewal in Salem. Then it’s on to St. Peter Street, past the Old Jail and the Jailkeepers’s House (below), right on Bridge, and then right again, onto Winter Street.

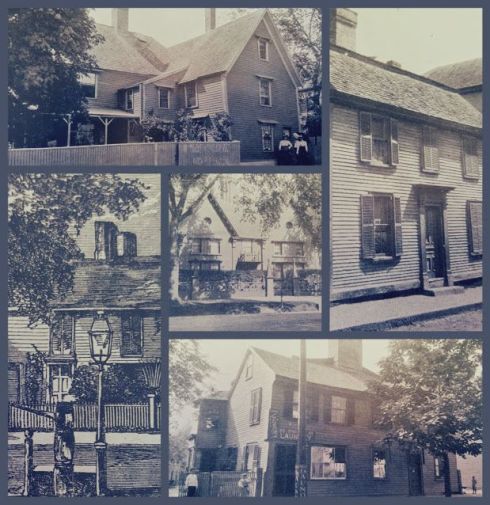

Winter Street

Winter Street

As you approach Salem Common, you must bear left and head for the east side, as the west side is the territory of the Salem Witch “Museum.” There are some side streets with wonderful houses between the Common and Bridge Street which might be a bit more pleasant to traverse than the latter but you will be cutting close to the “Museum”: that’s why I always go with Winter. Once there, go straight by the Common on Washington Square East : you will pass the newly-renovated Silsbee Mansion, which long served as the party palace Knights of Columbus and has been converted into residential units with a substantive addtion and exterior restoration, and one of my favorite houses on the Common, the Baldwin Lyman House.

On Washington Square East.

On Washington Square East.

Washington Square East will take you right to Essex Street: cross and go down the walkway adjacent to the first-period Narbonne House into the Salem Maritime National Historic Site. No witches or pirates here: you’re safe! I love the garden behind the Derby House: I think it is probably at its best in June when the peonies are popping but it’s a great place to go all spring and summer and even in the fall. On Derby Street, you can turn left and go down to the House of the Seven Gables or go straight down Derby Wharf: I went to the end of the wharf on this particular walk. The Salem Arts Association is right here too, but beware: there is a particularly ugly witch on its right so shade your view lest your zen walk be disturbed.

Salem Maritime National Historic Site and the Salem Arts Association.

Salem Maritime National Historic Site and the Salem Arts Association.

Back on Derby. Adjacent to the Custom House is a wonderful institution: the Brookhouse Home for Women, established in 1861! The Home is located in the former Benjamin Crowninshield Mansion, and it is very generous with its lovely grounds, which provide my favorite view of Derby Wharf. I always stop in here, and then I work my way back up to Essex Street on one side street or another. Essex Street east and west are wonderful places to walk, but the pedestrian-mall center is witch-central: a particularly dangerous corner is Essex and Hawthorne Boulevard, where the Peabody Essex’s historic houses face some of the ugliest signs in town. It’s a real aesthetic clash: gaze at the beautiful Gardner-Pingree House, but don’t turn around! If you want to go to the main PEM buildings or the Visitors’ Center further down Essex, approach from Charter Street north on another “street” that no longer exists: Liberty Street.

From the Brookhouse Home to the PEM’s row of historic houses on Essex Street. Memorial stone in the Brookwood garden: Miss Amy Nurse, RN, an Army Nurse (1916-2013).

From the Brookhouse Home to the PEM’s row of historic houses on Essex Street. Memorial stone in the Brookwood garden: Miss Amy Nurse, RN, an Army Nurse (1916-2013).

Charter Street is the location of Salem’s oldest cemetery, the Old Burying Point, recently restored and equipped with an orientation center located in the first-period Pickman House, which overlooks the Witch Trials Memorial. So this is a wonderful, meaningful place to visit, but beware: just beyond is the “Haunted Neighborhood” or “Haunted Witch Village” (whatever it is called) situated on the southern end of the former Liberty Street, abutting the cemetery. This is a cruel juxtaposition during Haunted Happenings, when you literally have a party right next to sacred places, but not too noticeable during the rest of the year, because for the most part witchcraft “attractions” create dead zones. But the tacky signage can still spoil your walk so avert your gaze as much as possible. Charter Street feeds into Front Street, Salem’s main shopping street, and from there you can find the path of least (traffic) resistance back to the McIntire Historic District, which is very safe territory. Broad, Chestnut, upper Essex and Federal Streets are lined with beautiful buildings, as are their connecting side streets, so take your pick. I usually just walk around until I get in my 10,000 steps: on this particular walk I ended up on Essex.

Charter, Front & upper Essex Streets.

Charter, Front & upper Essex Streets.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Winter Street

Winter Street

On Washington Square East.

On Washington Square East.

Salem Maritime National Historic Site and the Salem Arts Association.

Salem Maritime National Historic Site and the Salem Arts Association.

From the Brookhouse Home to the PEM’s row of historic houses on Essex Street. Memorial stone in the Brookwood garden: Miss Amy Nurse, RN, an Army Nurse (1916-2013).

From the Brookhouse Home to the PEM’s row of historic houses on Essex Street. Memorial stone in the Brookwood garden: Miss Amy Nurse, RN, an Army Nurse (1916-2013).

Charter, Front & upper Essex Streets.

Charter, Front & upper Essex Streets.

The Patton Homestead, Hamilton

The Patton Homestead, Hamilton

Ipswich: the Whipple & Heard houses and just a few beautifully preserved Colonials—there are so many more!

Ipswich: the Whipple & Heard houses and just a few beautifully preserved Colonials—there are so many more!

Newbury and Newburyport: one of my favorite houses in the County, on Newbury’s Lower Green, plus the Spencer-Pierce-Little

Newbury and Newburyport: one of my favorite houses in the County, on Newbury’s Lower Green, plus the Spencer-Pierce-Little

Frank Cousins photograph of the Bartoll painting; 1930 Port of Salem map, Boston Public Library & illustration from Lossing’s History of the United States of America (1913); Samuel Bartoll’s Corwin House, Peabody Essex Museum.

Frank Cousins photograph of the Bartoll painting; 1930 Port of Salem map, Boston Public Library & illustration from Lossing’s History of the United States of America (1913); Samuel Bartoll’s Corwin House, Peabody Essex Museum.

More idealized American imagery from Samuel Bartoll: Painted Hitchcock Chairs, James D. Julia

More idealized American imagery from Samuel Bartoll: Painted Hitchcock Chairs, James D. Julia