I spend a lot of time in cemeteries all year long (well perhaps not in the depths of winter) but in the weeks leading up to Memorial Day that time intensifies: late May is characterized by that heady mix of beautiful blooms and remembrance. Salem’s two larger cemeteries, Greenlawn and Harmony Grove, are nineteenth-century “garden cemeteries” which are beautiful places to wander and to remember, as they contain graves of soldiers who fought and died in the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World Wars One and Two, Korea and Vietnam. The two Salem men who were killed in Afghanistan, James Ayube and Benjamin Mejia, are buried in these cemeteries as well: the former at Harmony Grove and the latter at Greenlawn. In the center of town, Salem’s older cemeteries, at Charter, Broad and Howard Streets, contain the graves of Revolutionary War veterans, as well as those who fought in earlier colonial conflicts, and the Civil War. This is one of the more important aspects of living in an old settlement: you can feel the weight of history.

Harmony Grove is the cemetery where you feel the weight of the Civil War the most, or the “War to Preserve the Union” as its northern combatants called it (because that is what it was). Greenlawn has a G.A.R monument and many graves of Civil War soldiers, but there is something about Harmony Grove that feels more connected to that era. There is a central circle commemorating the young Salem men that died during the war, and survivors’ graves are interspersed throughout the cemetery: the grave of Luis Emilio, the Captain of the Mass. 54th is there. He survived the assault on Fort Wagner in South Carolina in 1863 and lived to tell the tale, but the grave of William P. Fabens, who died there the following year, is also at Harmony Grove.

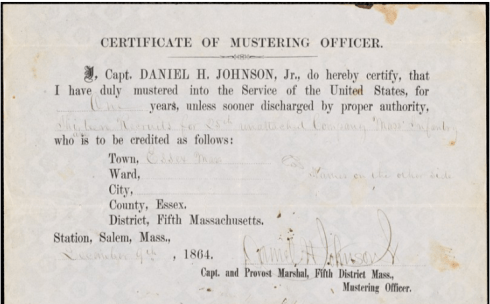

Stones can only tell you so much: if you want to want to know more, you need paper: the sources of the Civil War are plentiful and accessible in general but for Salem in particular, sparse, because of the removal of the Phillips Library. With its present pledge to digitize more of its collections, this situation might change, but for now we are dependent on other repositories for glimpses of Salem’s Civil War history. Given Salem’s role as a regional center in northeastern Massachusetts, I was able to piece together a paper trail through two state digital databases, the New York Heritage and Digital Commonwealth, and a few other sources: this trail does lead us to the battlefield (or camp nearby) but is more evocative of the war at home. Salem emerges as a busy place of mobilization and recruitment, where young men from all over Essex County were mustered into service and dispatched to the major regional training camp in Lynnfield. At the beginning of the war, this is a process of enthusiastic volunteerism, but as it wears on it’s all about bounties and quotas. Massachusetts Adjutant-General William Schouler cited his own correspondence in his two-volume History of Massachusetts in the Civil War (1868) including this representative instruction to an official in Newburyport: Recruit every man you can; take him to the mustering officer in Salem and take a receipt for him. After he is mustered into United States service, you shall receive two dollars for each man. The officer will furnish transportation to Lynnfield. Work, work: for we want men badly. The correspondence between Daniel Johnson, the mustering officer and Provost Marshal in Salem who was responsible for recruiting men from Essex County in the last 18 months of the war and officials in the small town of Essex illustrates the intensifying local effort to meet quotas established by the state and federal governments.

Recruiting posters from 1861-1863, New York Historical Society via New York Heritage; Town of Essex Civil War records, 1864 via Digital Commonwealth.

Recruiting posters from 1861-1863, New York Historical Society via New York Heritage; Town of Essex Civil War records, 1864 via Digital Commonwealth.

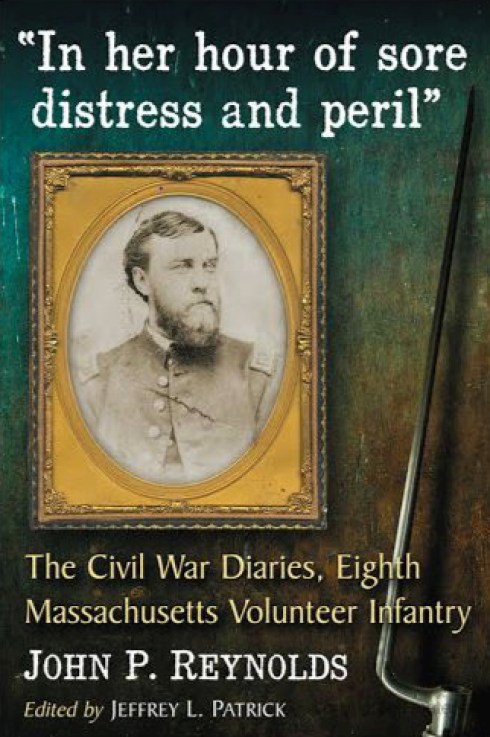

Official records are illuminating yet necessarily focused on logistics; more intimate perspectives, bringing us closer to the camp or battlefield, can be found in diaries and journals. Two Salem soldiers recorded and projected their personal perspectives during and after the war: John Perkins Reynolds and Herbert Valentine. Reynolds (a grandson of Elijah Sanderson who was briefly detained by the British on the even of the battles of Lexington and Concord!) kept a diary of his service in the opening months of the war with the Salem Zouaves (at the Clements Library at the University of Michigan, and available here in print), and also documented his reminiscences of his time with the Massachusetts 19th (at the Massachusetts Historical Society). Valentine’s journals, scrapbooks, and visual impressions of the war are also in several repositories, including the Wilson Library at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the Z. Smith Reynolds Library at Wake Forest University, the Phillips Library, and the National Archives, which has digitized his watercolors of wartime scenes.

Valentine’s Virginia vignettes, 1863-64, National Archives.

Valentine’s Virginia vignettes, 1863-64, National Archives.

These are not impressions that would have been available to contemporaries, but I think people who lived during the war would have have been exposed to its images and texts every day: posters, newspapers, the daily mail. A sea of Civil War envelopes survives, emblazoned with all sorts of colorful messages: surely this must be a fraction of what was produced and disseminated. According to its finding aid (which is online), the Phillips Library has 17 boxes of Civil War envelopes! Wow—-those will make quite a splash when they come online. My very favorite example (about which I wrote a whole blog post) depicting President Lincoln as the “Union Alchemist” was printed by Salem printers G.M. Whipple and A.A. Smith: I hope that there are more examples of their clever imagery in that Rowley vault.

Library Company of Philadelphia and Richard Frajola.

Library Company of Philadelphia and Richard Frajola.

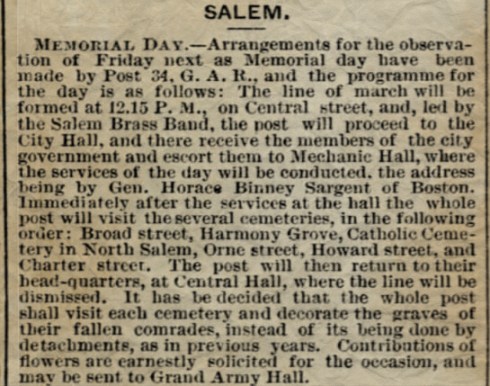

Newspaper accounts constituted a daily drumbeat and are thus too plenteous to consider here, but I did want to chart the beginnings of remembrance for this Memorial Day, so I looked at newspapers from the later 1860s and early 1870s—or so was my goal; I dug in and went quite a bit later. For the most part, the Salem story follows the national (or at least northeastern) pattern: in 1868 the first Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Army of the Republic declared May 30 to be Memorial Day and the Salem G.A.R obeyed his orders to the letter. I saw very few references to “Decoration Day”; Memorial Day seems to be have been the preferred designation right from the start. While local officials were invited to participate in the proceedings, the entire commemoration was a G.A.R affair until the early decades of the twentieth century. The only concerns expressed about the increasingly-ingrained “holiday” came right at its beginning and much later: an anonymous daughter of Civil War casualty expressed her concerns in 1870 that the proceedings were too commercialized, and certain members of the G.A.R leadership were profiting from supplying (see the C.H. Weber advertisement below), and much later the G.A.R itself expressed its concerns that a city-licensed circus was being allowed to operate on Memorial Day (see? protesting city-sanctioned circuses is a time-honored Salem tradition).

The evolution of Memorial Day: C.H. Webber outfits participants for the occasion, Salem Register, May 19, 1870; Boston Globe May 1873, 1923, and 1944: the last GAR members in Massachusetts, including Thomas A. Corson of Salem, who died later that year at age 103.

The evolution of Memorial Day: C.H. Webber outfits participants for the occasion, Salem Register, May 19, 1870; Boston Globe May 1873, 1923, and 1944: the last GAR members in Massachusetts, including Thomas A. Corson of Salem, who died later that year at age 103.

Madame Beavoir’s Painting

Madame Beavoir’s Painting

Madame Leroy and Rest in Peace; Revolutionary Dress Top (detail).

Madame Leroy and Rest in Peace; Revolutionary Dress Top (detail).

Marie Antoinette is Dead; Boucher’s Portrait of Madame de Pompadour (Neue Pinakothek, Munich); Passing and Violin of the Dead. All photographs by Fabiola Jean-Louis with more + commentary at her website:

Marie Antoinette is Dead; Boucher’s Portrait of Madame de Pompadour (Neue Pinakothek, Munich); Passing and Violin of the Dead. All photographs by Fabiola Jean-Louis with more + commentary at her website:

![Thanksgiving Salem_Observer_1849-11-24_[2]](https://i0.wp.com/streetsofsalem.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/thanksgiving-salem_observer_1849-11-24_2.jpg?resize=490%2C407&ssl=1)

Greenlawn Cemetery in Salem, and the 2016 memorial for Medal of Honor recipient Thomas Atkinson.

Greenlawn Cemetery in Salem, and the 2016 memorial for Medal of Honor recipient Thomas Atkinson.

The Massachusetts State House festooned for a G.A.R. encampment in 1927, Leslie Jones, Boston Globe; images from the History and Complete Roster of the Massachusetts Regiments, Minutemen of ’61 who Responded to the First Call of President Lincoln, April 15, 1861, to defend the Flag and Constitution of the United States (1910).

The Massachusetts State House festooned for a G.A.R. encampment in 1927, Leslie Jones, Boston Globe; images from the History and Complete Roster of the Massachusetts Regiments, Minutemen of ’61 who Responded to the First Call of President Lincoln, April 15, 1861, to defend the Flag and Constitution of the United States (1910).

Matthew Brady daguerreotype of Lander, Smithsonian; Jean Davenport Lander at about the same time, Harvard Theater Collection.

Matthew Brady daguerreotype of Lander, Smithsonian; Jean Davenport Lander at about the same time, Harvard Theater Collection.

One of Lander’s early road surveys, from Danvers to Georgetown, Massachusetts, State Library of Massachusetts; Albert Bierstadt’s

One of Lander’s early road surveys, from Danvers to Georgetown, Massachusetts, State Library of Massachusetts; Albert Bierstadt’s  Jean Margaret Davenport Lander as a bride in 1860 and Hester Prynne in 1877. Below: I’m assuming the friendship of Lander and Albert Bierstadt brought the latter to Salem at some point, because Christie’s has a Bierstadt landscape titled Salem, Massachusetts up for

Jean Margaret Davenport Lander as a bride in 1860 and Hester Prynne in 1877. Below: I’m assuming the friendship of Lander and Albert Bierstadt brought the latter to Salem at some point, because Christie’s has a Bierstadt landscape titled Salem, Massachusetts up for  Albert Bierstadt, Salem, Massachusetts, 1861.

Albert Bierstadt, Salem, Massachusetts, 1861.

British soldier Leonard Knight and the bullet-ridden

British soldier Leonard Knight and the bullet-ridden

Framed Sampler by Sarrah [Sarah] Ann Pollard, 1818, Salem, Massachusetts.

Framed Sampler by Sarrah [Sarah] Ann Pollard, 1818, Salem, Massachusetts.