Salem is kind of an odd statue city, in my opinion. Some statues get placed by small constituencies, while others are erected in inappropriate locales. Salem’s most recent statue, of educator and abolitionist Charlotte Forten, is an unfortunate example of the latter. Charlotte certainly deserves a statue and I think her representation is lovely, but placing a diminuative bronze in the concrete “park” that is named for her but yet has nothing to do with her, in a space that has been compromised by giant tacky pirate illustrations and a turquoise wooden bar, emphasizes her fragility rather than her strength. She looks incongruous there and I don’t like to visit her: there’s no context. Poor Roger Conant, the founder of Salem, has a very strong presence which is unfortunately diminished by his location adjoining the Witch Museum—everyone who comes to Salem thinks he is a witch even though, of course, there were no witches. I think Nathaniel Hawthorne is well-served by his location on Hawthorne Boulevard, but a bit further to the south is Fr. Theobold Mathew, the Irish temperence “apostle” who visited Salem in 1849. No one knows who he is or cares about him at all; indeed, if there was more knowledge of Mathew I am sure his statue would be removed as he reneged on his original abolitionist stance when he came to America—Charles Lenox Remond, who met Mathew in Ireland and collected his signature on his “Irish Address” to Irish Americans denouncing slavery, must be rolling in his grave! I’m not commenting on Samantha; I think everyone who reads this blog knows how I feel about that atrocity. So that brings me to the memorial statue for Joseph Hodges Choate on Essex Street: an “entrance” statue which Salem needs more of I think, but also rather mysterious. The statue has been moved once before, not too far from its original location, but another plan to move it to a far less conspicuous place a few years ago brought forth a curious opposition, as it was clear that no one really knew who Choate was.

I didn’t really know much about Choate either, to be honest, but I started gathered the basics of his biography after visiting his summer house in the Berkshires, Naumkeag, a decade ago. I added a few details over the years—he was impressive and interesting to me because he seemed like a self-made man, not the usual “son of a prosperous Salem shipowner” type. His father was a busy Salem physician who managed to send four of his sons to Harvard, including Joseph, so I guess he wasn’t that self-made: Harvard was certainly a good start. He decided to practice law in New York City and was almost immediately attached to a well-known firm. As a litigator, he had a knack, or perhaps his mentors advised him, to take up cases that had national consequences or drew national attention: relating to the income tax and Chinese exclusion, reversing a famous Civil War court-martial. He was a very civic-minded New Englander in New York, and part of a group of influential reformers who took on Boss Tweed. He was also very much of a public intellectual, giving lots of speeches and writing popular periodical pieces. With his wife Carrie, he was active in New York’s social scene, and was one of the founders of both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Natural History. The capstone to his long successful career was his appointment as Ambassador to Great Britain in 1899, a position he occupied until 1905.

Vanity Fair “Spy” caricature of Joseph Hodges Choate, 1899.

Late last year, I came across Choate’s “fragmentary” biography, The life of Joseph Hodges Choate: as gathered chiefly from his letters, and read it over Christmas. Several of his letters leaped off the page, so I want to go back to Choate’s early days in New York City, when he experienced, recorded, and played a role in one of our nation’s worst insurrections: the Draft Riots of July 1863. Following the passage of the Enrollment Act of 1863 and the first draft lottery in July, thousands of working class New Yorkers, primarily Irish immigrants, began rioting, looting and lynching in protest of the perceived inequalities of the draft, from which people of means could escape by purchasing the services of a substitute for $300 and disenfranchised African Americans were exempt. Given the near concurrence of Gettysburg and some severely compromised leadership, the City seemed powerless to stop the mob, so the riots became increasingly violent and specifically targeted against active abolitonists and African Americans for four bloody days in mid-July until the New York militia and Federal troops arrived. The estimated death toll is all over the place, anywhere from more than a hundred to more than a thousand; the destruction seemed inestimable but was ultimately estimated at between $1.5 million and five million (in 1863 dollars) and the horrors still seem horrible: at the very least, eleven black men were “murdered with horrible brutality” and NYC police superintendendant John Alexander Kennedy, an Irish-American himself, was beaten to a bloody pulp and stabbed 70 times by the mob. The Colored Orphans Asylum was burned to the ground.

The girls’ playground at the Colored Orphans Asylum before the riots; Illustrated London News depiction of its burning.

Choate’s descriptions of the Riots in a succession of letters to his mother back in Salem are raw; he’s clearly struggling with the cruelty and violence he is seeing. These observations will be consequential, as we will see, and this experience shaped his outlook and politics for the rest of his life. He happened to live near a rather famous abolitionist family with whom he had become friends, Abigail Hopper Gibbons and her husband James, both Quakers and seemingly tireless advocates for abolition and other social reforms. Choate observed that “nothing could be more simple and almost idyllic than the life that these Quakers let, and the house of Mrs. Gibbons was a great resort of abolitionists and extreme antislavery people from all parts of the land, as it was one of the stations of the underground railroad by which fugitive slaves found their way from the South to Canada. I have dined with that family in company with William Lloyd Garrison, and sitting at the table with us was a jet-black negro who was on his way to freedlom. On the second day of the riots, when both Mr. and Mrs. Gibbons were in other parts of the city, a mob descended on their house at 339 West 29th Street, with only their two teenaged daughters at home. A neighbor tried to help defend the house but was cut down by the crowd, while the girls escaped next door where Choate found them soon after. He continues: They threw themselves into my arms, almost swooning. I immediately got a carriage, and got them over a dozen adjoining roofs, and in a few minutes we were all safely at our door. Their house is not very much injured, but all the sacred associations of a home of 25 years are gone. Yes, they had to flee over the attached roofs of the townhouses of West 29th Street, now the Lamartine Place Historic District of New York City.

A contemporary view of the attack on “Mrs. Gibbon’s’House”; Lamartine Place, getting crowded out but still intact in the 1920s; the Gibbons house is in the middle. New York Public Library Digital Gallery.

Choate elaborates quite a bit in his letters home about the atrocities of those hot July days, referencing uncontrollable and unprecedented (since the French Revolution in his view) violence and the complicity of state and local officials. In a scenario which seems very reminiscent of President Trump’s embrace of the Charlottesville torchbearers, New York Governor Horatio Seymour addressed the rioters as his “friends,” horrifying Choate. It’s personal rather than political: the entire Gibbons family was sheltered in his home, along with several African American refugees, for no negro was safe out of doors. Choate’s accounts of his experiences had a long-ranging impact, even reaching our own time. A 13-year battle between a man who purchased the Hopper Gibbons House and sought (and actually started) to build a fifth story concluded in 2017 with an order to cease, desist, and restore the house to its original four stories. Preservationists relied heavily on the Choate accounts, which documented the house as a stop on the Underground Railroad and emphasized the historical (not just aesthetic) importance of the roofline which enabled the Gibbons girls’ escape. So now when I look at the embodiment of liberty enshrined on the Choate statue right here in Salem, I think of someone who was a lot more than a gifted litigator and influential diplomat. Joseph Hodges Choate responded bravely and earnestly to the challenges of his own time, and kept a record so that we might remember, learn, and preserve in ours.

The Hopper Gibbons House under siege; the stucco had come before, but the fifth floor has now been removed.

The bundle handkerchief as art: Alfred Denghausen, 1936, National Gallery of Art.

The bundle handkerchief as art: Alfred Denghausen, 1936, National Gallery of Art.

Not blue and white, but the best I could do: a recipe card from the 1950s; Mr. Hathaway’s Bakery or the “Old Bakery” (now the Hooper Hathaway House on the campus of the House of the Seven Gables) in its original location at 21 Washington Street, Historic New England; Elisabeth Merritt Gosse in 1905, upon the occasion of the dedication of a boulder commemorating her father’s regiment near Salem Common.

Not blue and white, but the best I could do: a recipe card from the 1950s; Mr. Hathaway’s Bakery or the “Old Bakery” (now the Hooper Hathaway House on the campus of the House of the Seven Gables) in its original location at 21 Washington Street, Historic New England; Elisabeth Merritt Gosse in 1905, upon the occasion of the dedication of a boulder commemorating her father’s regiment near Salem Common. Elisabeth Merritt Gosse was referencing the OLD Salem Athenaeum, now one of the Peabody Essex Museum’s empty buildings further up on Essex Street, but as I happened to be walking by the present one today, I snapped this photograph.

Elisabeth Merritt Gosse was referencing the OLD Salem Athenaeum, now one of the Peabody Essex Museum’s empty buildings further up on Essex Street, but as I happened to be walking by the present one today, I snapped this photograph.

A Half Century in Salem, and two photographs of Marianne Cabot Devereux Silsbee from her 1861 photographic album at the Phillips Library in Rowley (PHA 58): the first dated 1851 and the second 1861.

A Half Century in Salem, and two photographs of Marianne Cabot Devereux Silsbee from her 1861 photographic album at the Phillips Library in Rowley (PHA 58): the first dated 1851 and the second 1861.

The Silsbee Mansion on Salem Common in 1884, George H. Walker; Memory and Hope (1851); Title page of My Grandmother’s Mirror (Essex County Collection, Phillips Library,

The Silsbee Mansion on Salem Common in 1884, George H. Walker; Memory and Hope (1851); Title page of My Grandmother’s Mirror (Essex County Collection, Phillips Library,

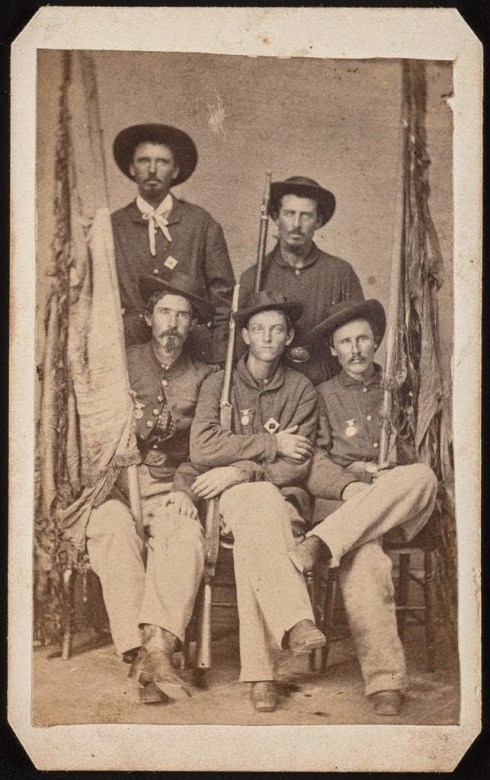

Alpheus Crosby and several (not all!) of his equally successful siblings, the sons of Dr. Asa Crosby of Sandwich, New Hampshire. The Normal School at Salem on Broad and Summer Streets during Crosby’s tenure, c. 1857-1865, Salem State University Archives; just a few of the Salem institutions to which Alpheus Crosby volunteered considerable time: the Salem Lyceum, the Salem Athenaeum (then at Plummer Hall) and the Essex Institute, Cousins collection of the Phillips Library of the Peabody Essex Museum via Digital Commonwealth; Professor Crosby’s bestselling series of Greek textbooks, 1860.

Alpheus Crosby and several (not all!) of his equally successful siblings, the sons of Dr. Asa Crosby of Sandwich, New Hampshire. The Normal School at Salem on Broad and Summer Streets during Crosby’s tenure, c. 1857-1865, Salem State University Archives; just a few of the Salem institutions to which Alpheus Crosby volunteered considerable time: the Salem Lyceum, the Salem Athenaeum (then at Plummer Hall) and the Essex Institute, Cousins collection of the Phillips Library of the Peabody Essex Museum via Digital Commonwealth; Professor Crosby’s bestselling series of Greek textbooks, 1860.

Post-“retirement”: advocacy for radical reconstruction and “impartial” suffrage, 1865-66, Library of Congress; just one donation to the Normal School at Salem. 111 Federal Street in Salem, the residence of Professor and Mrs. Crosby, along with Amy Lydia and Lucy B. Dennis, during the 1860s.

Post-“retirement”: advocacy for radical reconstruction and “impartial” suffrage, 1865-66, Library of Congress; just one donation to the Normal School at Salem. 111 Federal Street in Salem, the residence of Professor and Mrs. Crosby, along with Amy Lydia and Lucy B. Dennis, during the 1860s.

Pages from Gardner’s Sketchbook, Volume One at Duke University Library’s

Pages from Gardner’s Sketchbook, Volume One at Duke University Library’s

Calvin Townes of the First Regiment; the surviving Regiment at Salem Willows, 1890; Memorials at Spotsylvania and in the Essex Institute, from the History of the First Regiment of Heavy Artillery, Massachusetts Volunteers, formerly the Fourteenth Regiment of Infantry, 1861-1865 (1917); the demolished Harris Farm.

Calvin Townes of the First Regiment; the surviving Regiment at Salem Willows, 1890; Memorials at Spotsylvania and in the Essex Institute, from the History of the First Regiment of Heavy Artillery, Massachusetts Volunteers, formerly the Fourteenth Regiment of Infantry, 1861-1865 (1917); the demolished Harris Farm.

The Munroe House on Lexington Green (which is presently for

The Munroe House on Lexington Green (which is presently for

The Jonathan Corwin (Witch) House, in all of its incarnations in an early 20th century postcard, Historic New England; in 1947 as restored by Gordon Robb and Historic Salem, Inc., and photographed by Harry Sampson, and in the tourist attraction in the 1950s, Arthur Griffin via Digital Commonwealth.

The Jonathan Corwin (Witch) House, in all of its incarnations in an early 20th century postcard, Historic New England; in 1947 as restored by Gordon Robb and Historic Salem, Inc., and photographed by Harry Sampson, and in the tourist attraction in the 1950s, Arthur Griffin via Digital Commonwealth.