For a blog with Salem in its title, I have written relatively few posts about witches, or Hawthorne. Faithful followers will understand the former slight, but I haven’t really discussed my thoughts about Hawthorne here, I think. Essentially I am not a fan of the man or his works. He strikes me as very haughty and melancholy and over-dramatic and not subtle and there are particular aspects of his biography and character which I really don’t like, particularly his attitude towards race and any expression of social reform and his treatment of Salem sculptor Louise Lander in Rome. I don’t think his novels have aged well: just a brief comparison with a near-contemporary like Jane Austen will illustrate what I mean. Despite her smallish world, much smaller than that of Hawthorne, her works are classic and current because she understood people much better than he did. It’s no revelation that Hawthorne was a misanthrope, but it’s difficult to get past that, really, at least for me. In the last year or so, I have been trying to get closer to Hawthorne by reading his notebooks: they’re by my bedside in nice editions and I have been been dipping into them regularly. I started with the European notebooks (English, Italian) and then last month picked up the “lost” notebook, which he kept in Salem from 1835-1841. And now I find myself looking at him not altogether but a bit differently: he seems young, very impressionable, very curious, but still judgemental. True to form, young Nathaniel was not really social in any sense in the world—he even calls himself a recluse—but he is a good observer so he is a good source for Salem. This notebook was published by his widow Sophia in the 1860s in a highly-edited American version: most critics use the word bowdlerized. She took out all the interesting bits! More than a century later it was rediscovered, and published in a 1978 facsimile edition by the Pierpont Morgan Library, which has the original manuscript in its collection.

The entries in the notebooks are basically observations interspersed with story ideas. Hawthorne is always walking around Salem: in general (but not always) he prefers to walk away from the city center into nature, to the Willows and Winter Island, to North Salem, along the coastline. Sometimes something he sees will prompt a story idea but usually the story ideas are coming out of his head rather then his environment. He seems to be practicing describing settings, rather than people’s characters. Sophia took out his descriptions of a well-dressed drunken couple observed on a trip to Boston, and young ladies bathing at the Salem shore, but they are restored in the 1978 publication, and another (really great, but again somewhat detached) discourse on society is a great description of the celebration of July 4 (his birthday!) on Salem Common. I made a list of highlights, but you will surely have your own: the lost notebook, which is also Hawthorne’s Salem notebook, is a quick, engaging read.

On Nature: Hawthorne loves the shoreline and describes its features in great detail. He seems to relish “marine vegetables” in general of an olive color, with round, slender, snake-like stalks, four or five feet long, and a great leaf, twice as long, and nearly two feet broad; these are the herbage of the deep-sea. I had never heard of samphire, or mutton sauce, growing somewhat like asparagus; it is an excellent salad at this season, salt yet with an herb-like vivacity, and eating tender. A succession of cookbook authors agree: where have I been? It’s all over Juniper Point, along with jellyfish. Hawthorne also liked to observe farmland and farm animals, especially pigs, which surely are types of unmitigated sensuality; — some standing /^in/ the trough, in the midst of their own and others victuals; — some thrusting their noses deep into the filth; — some rubbing their hinder-ends against a post; — some huddled together, between sleeping and waking, breathing hard; — all wallowing in each other’s defilement; — a great boar -going /swaggering/ about, with lewd actions; — a big-bellied sow, waddling along, with her swag-paunch. He’s judgemental even of PIGS.

Samphire illustration by Mrs. Henry Perrin from British Flowering Plants (1914).

I would have like to have seen this, but the Bulfinch Almshouse/Hospital was demolished in 1954: The grass about the hospital is rank, being trodden, probably, by nobody but me. The representation of a vessel under sail, cut with a pen knife, on the corner of the house. I would have liked to have seen both the building and the vessel carving.

The Salem Almshouse and Hospital of Contagious Diseases built 1816, Frank Cousins glass lantern slide, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum via Digital Commonwealth.

Looking glasses: Young Hawthorne clearly loved nature, but he was a materialist too, interested in and inspired by structures and objects. I found multiple reference to mirrors: To make one’s own reflection in a mirror the subject of a story. An old looking-glass—somebody finds out the secret of making all the images that have been reflected in it pass back again across its surface.

Wondrous Forces: Many of the story ideas which pop up in the notebook involve plots in which some sort of wondrous force drives the action. I like this one: a person to be writing a tale, and to find that it shapes itself against his intentions; that the characters act otherwise than he thought; that unforeseen events occur; and a catastrophe which he strives in vain to avert. It might shadow forth his own fate — he having made himself one of the personages. Hawthorne seems very interested in all forms of magic, particularly of the kind that alters forms, like alchemy. What I think was the Deliverance Parkman House (demolished just before Hawthorne began his notebook entries; he must have seen it) draws forth several alchemical connections: the house on the eastern corner of North & Essex streets (supposed to have been built about 1640) had, say sixty years later, a brick turret erected, wherein one of the ancestors of the present occupants used to practice alchemy. He was the operative; a scientific person in Boston the director. There have been other Alchemysts of old in this town — one who kept his fire burning seven weeks, and then lost the elixir by letting it go out.

Stereoview of a drawing of the Parkman House, New York Public Library Digital Gallery.

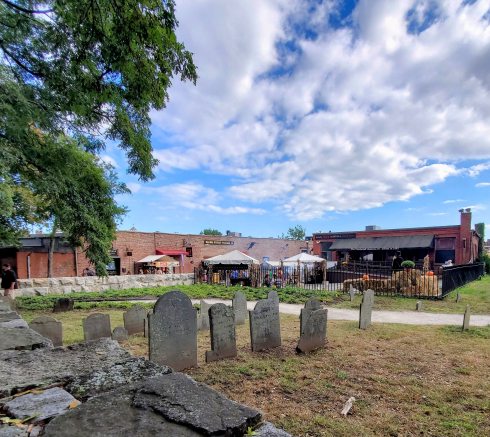

Macabre bits: Hawthorne’s interest in the dead and dying are pretty well-known and there are certainly lots of death references in the notebook: one story idea involves a young couple [who] take up their residence in a retired street of a large town. One day, she summons several of the neighbors in, and shows them the dead body of her husband. That’s it! I wonder where he was going with that? He is of course enchanted with and by the Old Burying Ground on Charter Street where he encounters the grave of his witch-trial judge ancestor and the famous epitaph of Nathaniel Mather, “an aged person that had seen but nineteen winters in the world.” Hawthorne admits that he is quite considerably affected by these words, which he himself revealed to the world when I had away the grass from the half buried stone, and read the name.

July 4: Probably my favorite entry is Hawthorne’s depiction of a very festive Fourth in Salem in 1838. It was a “very hot, bright sunny day,” and the town was “much thronged”. On the Common were booths selling gingerbread &c. sugar-plums and confectionery, spruce-beer, lemonade. Spirits forbidden, but probably sold stealthily. On the top of one of the booths a monkey, with a tail two or three feet long. He is fastened by a cord, which, getting tangled with the flag over the booth, he takes hold and tries to free it. The object of much attention from the crowd, and played with by the boys, who toss up ginger bread to him. He goes on to describe more of the festivity, but he can’t help himself from commenting on the “plebianism” of the crowd!

True Crime via Wax Figures: A very festive July 4th/birthday for Hawthorne as he also attended an exhibition of wax figures which made quite an impression on him. Wax-figure displays had been happening in Salem from at least the 1790s: they were often patriotic or religious in theme, but this particular “statuary” consisted almost wholly of murderers and their victims; — Gibbs and Wansley the Pirates; and the Dutch girl whom Gibbs kept and finally murdered. Gibbs and Wansly were admirably done, as natural as life; and many people, who had known Gibbs, would not, according to the showman, be convinced that this wax figure was not his skin stuffed. The two pirates were represented with halters round their necks, just ready to be turned off; and the sheriff behind them with his watch, waiting for the moment. The clothes, halters, and Gibbs’ hair, were authentic. E K. Avery and Cornell, the former a figure in black, leaning on the back of a chair, in the attitude of a clergyman about to pray; — an ugly devil, said to be a good likeness. Ellen Jewett and R. P. Robinson; — she dressed richly in extreme fashion, and very pretty; he awkward and stiff, it being difficult to stuff a figure to look like a gendeman. The showman seemed very proud of Ellen Jewett, and spoke of her somewhat as if this was figure was a real creature. Strang and Mrs. Whipple, who together murdered the husband of the latter. Lastly the Siamese Twins. The showman is careful to call his exhibition the “Statuary”; he walks to and fro before the figures, talking of the history of the persons, the moral lessons to be drawn therefrom, and especially the excellence of the wax- work. Gibbs and Wansley were notorious pirates, Ellen (Helen) Jewett was a Maine girl who became a prostitute in New York City and her murder in the spring of 1836 triggered sensationalist headlines for the rest of the year as R.P. Robinson was tried and acquitted of the crime. E.K. Avery was Ephraim Kingsbury Avery, a Rhode Island Methodist minister accused of murdering a factory worker in his congregation named Sarah Cornell whom he had impregnated: he too was aquitted and this was another sensational murder case involving a (very) lasped clergymen which perhaps inspired The Scarlet Letter. In yet another notorious case, Jesse Strang and Elsie Whipple conspired to murder the latter’s husband outside Albany in 1827: she was acquitted and he was executed. I guess “Siamese twins” refers to the conjoined Bunker twins from Thailand who were thrown in here for good sensationalistic measure.

Cornell Digital Collections.

Social Commentary: Hawthorne does not seem to be interested in the contentious causes of his time and place. Salem was characterized by dynamic temperance and abolition movements in the 1830s, and he makes no mention of them in his notebook except for another story idea, a sketch to be given of a modern reformer — a type of the extreme doctrines on the subject of slaves, cold-water, and all that. He goes about the streets haranguing most eloquently, and is on the point of making many converts, when his labors are suddenly interrupted by the appearance of a keeper of a mad-house, whence he has escaped.

I pinched this photo of Hawthorne’s wax figure at the Salem Wax Museum of Witches & Seafarers from the author J.W. Ocker’s website, Odd Things I’ve Seen. In “Wax City,” Ocker observes that Salem tells its history through wax museums, and I agree, although I would put quotations around the word “museums.” Ocker wrote the great book The Season With the Witch about his residency in Salem during Haunted Happenings in 2015, and since Salem’s tourism has escalated so much over the past decade, I think he should return for a sequel.

Winter Street

Winter Street

On Washington Square East.

On Washington Square East.

Salem Maritime National Historic Site and the Salem Arts Association.

Salem Maritime National Historic Site and the Salem Arts Association.

From the Brookhouse Home to the PEM’s row of historic houses on Essex Street. Memorial stone in the Brookwood garden: Miss Amy Nurse, RN, an Army Nurse (1916-2013).

From the Brookhouse Home to the PEM’s row of historic houses on Essex Street. Memorial stone in the Brookwood garden: Miss Amy Nurse, RN, an Army Nurse (1916-2013).

Charter, Front & upper Essex Streets.

Charter, Front & upper Essex Streets.

Major Thomas Leonard’s funeral elegy, Library of Congress; a mourning ring for Edward Kitchen of Salem, Yale University Art Gallery; Announcement of the 1742 Act; Charles Apthorp portrait by Robert Feke (Cleveland Museum of Art) and a list of the 95 gloves dispensed by his family on the occasion of his 1737 funeral,

Major Thomas Leonard’s funeral elegy, Library of Congress; a mourning ring for Edward Kitchen of Salem, Yale University Art Gallery; Announcement of the 1742 Act; Charles Apthorp portrait by Robert Feke (Cleveland Museum of Art) and a list of the 95 gloves dispensed by his family on the occasion of his 1737 funeral,