I would really love to buy the toleration rationale that is used almost universally to justify Salem’s exploitation of the 1692 Witch Trials for commercial gain, but I have several issues. The argument goes like this: yes, we had a terrible tragedy here in 1692, but now we owe it to civilization to spread awareness of the intolerance of that community in order to raise awareness of intolerance in our own time. If we can make money at the same time, so be it, but it’s really all about teaching tolerance. I’ve written about this before, several times, so I’m not going to belabor the point, but I think this rationale reinforces a notion among some—actually many—that the victims of 1692 were doing something that was in some way aberrant or diverse, when in fact they were just plain old pious Protestants like their neighbors and accusers. The focus on toleration is supposed to connect the past to the present, but more than anything, it privileges the present over the past. My other problem with the toleration rationale is the exclusivity of its application: only to the Witch Trials, the intolerant episode with the most income-generating potential. We seldom hear of any other moments of intense intolerance in Salem’s history: the fining, whipping, and banishment of separatists, Baptists and Quakers in the seventeenth century, the anti-Catholicism and nativism of two centuries later. Certainly the Witch Trials were dramatic, but so too was the intense persecution in Massachusetts in general and Salem in particular over a slightly longer period, from 1656-1661: just read the title pages of these two incredibly influential texts which documented it.

Edward Burrough, A Declaration of the Sad and Great Persecution and Martyrdom of the People of God, called Quakers, in New England, for the Worshiping of God (1661; Christie’s —-the whole text can be found here); George Bishop, New England judged, not by man’s, but the spirit of the Lord: and the sum sealed up of New-England’s persecutions being a brief relation of the sufferings of the people called Quakers in those parts of America from the beginning of the fifth month 1656 (the time of their first arrival at Boston from England) to the later end of the tenth month, 1660 (1661; Doyle’s—the whole text is here).

The whipping, scourging, ear-cutting, hand-burning, tongue-boring, fining, imprisonment, starvation, banishment, execution, and attempted sale into slavery of Massachusetts Quakers by the colonial authorities is documented in almost-journalistic style by Edward Burrough and George Bishop and the former’s audience with a newly-restored King Charles II in 1661 resulted in a royal cease and desist missive carried straight to Governor Endicott by Salem’s own Samuel Shattuck, exiled Quaker and father of the Samuel Shattuck who would testify against Bridget Bishop in 1692. So yes, the Quakers accused the Puritans of intolerance far ahead of anyone else, and their detailed testimony offers many opportunities to explore an emerging conception of toleration in historical perspective: we don’t have to judge because they do. Every once in a while, an historical or genealogical initiative sheds some light on Salem’s Quakers—indeed, the Quaker Burying Ground on Essex Street was adorned by a lovely sign this very summer by the City, capping off some important restoration work on some of the stones—but their story is not the official/public/commercial Salem story: that’s all about “witches”.

Much of Salem’s Quaker history is still around us: the Essex Institute reconstructed the first Quaker Meeting House in 1865 and it is still on the grounds of the PEM’s Essex Street campus (Boston Public Library photograph via Digital Commonwealth); the c. 1832 meeting house formerly at the corner of Warren and South Pine Streets, Frank Cousins photograph from the Phillips Library Collection at Digital Commonwealth; the c. 1847 meeting house–now a dentist’s office overlooking the Friends’ Cemetery on upper Essex Street; Samuel Shattuck’s grave in the Charter Street Cemetery, Frank Cousins, c. 1890s, Phillips Library Collection at Digital Commonwealth.

Quakers can’t compete with “witches”, any more than factory workers, soldiers, inventors, poets, suffragists, educators, or statesmen or -women can: they’re just not sexy enough for a city whose “history” is primarily for sale. There was a time when I thought we could get the Bewitched statue out of Town House Square, but no more: it will certainly not be replaced by a Salem equivalent of the Boston memorial to Mary Dyer, one of the Boston Quaker “Martyrs”. The placement of a fictional television character in such a central place—just across from Salem’s original meeting house–and not, say, a memorial to Provided Southwick, whose parents were banished to Long Island, dying there in “privation and misery”, whose brother was whipped from town to town, and who would have been sold into slavery (along with another brother) near this same square if not for several tolerant Salem ship captains*, is a bit unbearable, but that’s Witch City. Apparently grass just won’t grow in this little sad space, so soon we will see the installation of artificial turf , which strikes me as completely appropriate.

“The Attempted Sale into Slavery of Daniel and Provided Southwick, son [children] of Lawrence and Cassandra Southwick, by Governor Endicott and his Minions, for being Quakers”, from the Genealogy of the descendants of Lawrence and Cassandra Southwick of Salem, Mass. : the original emigrants, and the ancestors of the families who have since borne his name (1881); *John Greenleaf Whittier tells Provided’s tale under Cassandra’s (more romantic?) name, and adds the “tolerant ship captains”: we only know that the sale did not go through. The Mary Dyer Memorial in front of the statehouse, Boston, Massachusetts.

Appendix: There was a very public attempt to place a memorial statue to the Quaker persecution in Salem by millionaire Fred. C. Ayer, a Southwick descendant, in the early twentieth century which you can read about here and here: the Salem City Council (or Board of Aldermen, as it was then called) objected to the representation of Governor Endicott as a tiger devouring the Quakers, so the proposed installation on Salem Common was denied. If the aldermen had read Burrough’s and Bishop’s accounts, I bet they would have been a bit more approving.

Like this:

Like Loading...

An abandoned farmhouse on Old Dana Road, and the Quabbin Reservoir.

An abandoned farmhouse on Old Dana Road, and the Quabbin Reservoir.

It seems as if Timothy Lindall’s gravestone has always been in the spotlight.

It seems as if Timothy Lindall’s gravestone has always been in the spotlight.

I feel particularly bad for Mr. and Mrs. Nutting, put to rest in a lovely calm neighborhood and now in the midst of the Salem Witch Village! And I really wish that Cousins had photographed my very favorite Charter Street gravestone: that of Mr. Ebenezer Bowditch. What are those carvings? Does anyone know?

I feel particularly bad for Mr. and Mrs. Nutting, put to rest in a lovely calm neighborhood and now in the midst of the Salem Witch Village! And I really wish that Cousins had photographed my very favorite Charter Street gravestone: that of Mr. Ebenezer Bowditch. What are those carvings? Does anyone know?

Old Burying Point Cemetery, Charter Street, Salem, October 2017 & 2018.

Old Burying Point Cemetery, Charter Street, Salem, October 2017 & 2018.

The Old Burying Point on Charter Street in mid-August.

The Old Burying Point on Charter Street in mid-August. The Old Burying Point in October via @Linden Tea on Flickr.

The Old Burying Point in October via @Linden Tea on Flickr. The Hearse House in Marlow, New Hampshire.

The Hearse House in Marlow, New Hampshire.

The McDermott Covered Bridge in Langdon (1864); the Meriden Bridge in Plainfield (1880); the Cilleyville (or Bog) Bridge in Andover (1887); the Keniston Bridge, also in Andover (1882); just two of Cornish’s FOUR covered bridges: somehow I missed the “Blow Me Down” Bridge and the Cornish-Windsor Bridge over the Connecticut River is

The McDermott Covered Bridge in Langdon (1864); the Meriden Bridge in Plainfield (1880); the Cilleyville (or Bog) Bridge in Andover (1887); the Keniston Bridge, also in Andover (1882); just two of Cornish’s FOUR covered bridges: somehow I missed the “Blow Me Down” Bridge and the Cornish-Windsor Bridge over the Connecticut River is

Salisbury & Fremont, New Hampshire.

Salisbury & Fremont, New Hampshire. Salem Register, August 19, 1841.

Salem Register, August 19, 1841.

Pages from Gardner’s Sketchbook, Volume One at Duke University Library’s

Pages from Gardner’s Sketchbook, Volume One at Duke University Library’s

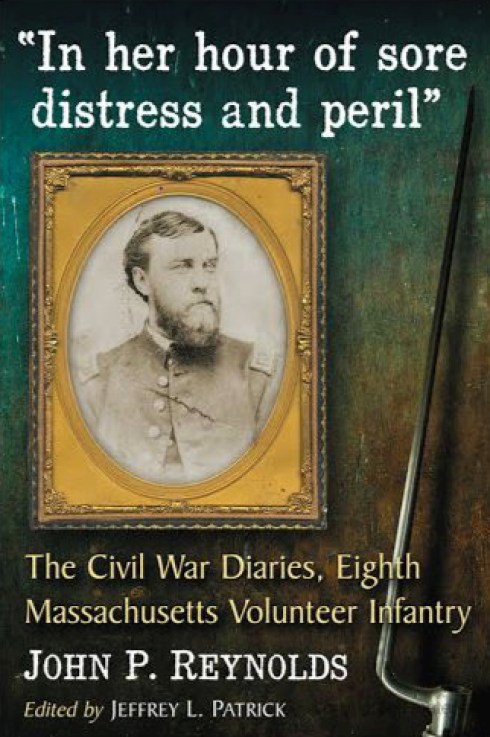

Calvin Townes of the First Regiment; the surviving Regiment at Salem Willows, 1890; Memorials at Spotsylvania and in the Essex Institute, from the History of the First Regiment of Heavy Artillery, Massachusetts Volunteers, formerly the Fourteenth Regiment of Infantry, 1861-1865 (1917); the demolished Harris Farm.

Calvin Townes of the First Regiment; the surviving Regiment at Salem Willows, 1890; Memorials at Spotsylvania and in the Essex Institute, from the History of the First Regiment of Heavy Artillery, Massachusetts Volunteers, formerly the Fourteenth Regiment of Infantry, 1861-1865 (1917); the demolished Harris Farm.

The Munroe House on Lexington Green (which is presently for

The Munroe House on Lexington Green (which is presently for

The Jonathan Corwin (Witch) House, in all of its incarnations in an early 20th century postcard, Historic New England; in 1947 as restored by Gordon Robb and Historic Salem, Inc., and photographed by Harry Sampson, and in the tourist attraction in the 1950s, Arthur Griffin via Digital Commonwealth.

The Jonathan Corwin (Witch) House, in all of its incarnations in an early 20th century postcard, Historic New England; in 1947 as restored by Gordon Robb and Historic Salem, Inc., and photographed by Harry Sampson, and in the tourist attraction in the 1950s, Arthur Griffin via Digital Commonwealth.

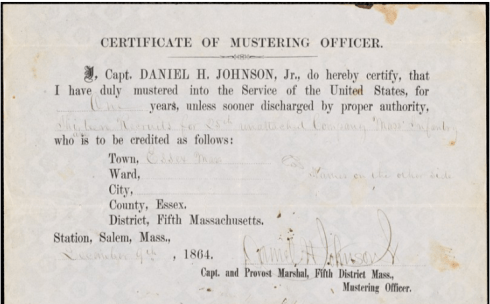

Recruiting posters from 1861-1863, New York Historical Society via New York Heritage; Town of Essex Civil War records, 1864 via Digital Commonwealth.

Recruiting posters from 1861-1863, New York Historical Society via New York Heritage; Town of Essex Civil War records, 1864 via Digital Commonwealth.

Valentine’s Virginia vignettes, 1863-64, National Archives.

Valentine’s Virginia vignettes, 1863-64, National Archives.

Library Company of Philadelphia and Richard Frajola.

Library Company of Philadelphia and Richard Frajola.

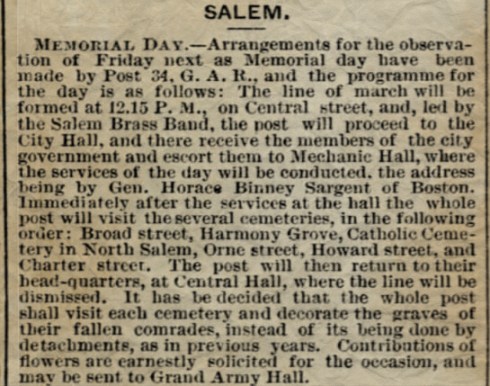

The evolution of Memorial Day: C.H. Webber outfits participants for the occasion, Salem Register, May 19, 1870; Boston Globe May 1873, 1923, and 1944: the last GAR members in Massachusetts, including Thomas A. Corson of Salem, who died later that year at age 103.

The evolution of Memorial Day: C.H. Webber outfits participants for the occasion, Salem Register, May 19, 1870; Boston Globe May 1873, 1923, and 1944: the last GAR members in Massachusetts, including Thomas A. Corson of Salem, who died later that year at age 103.

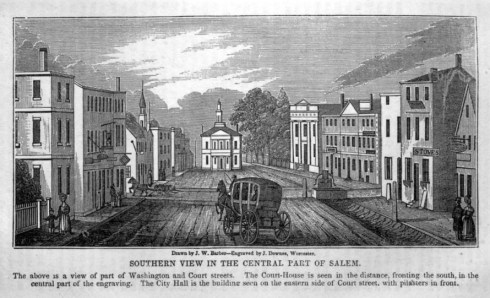

Salem Gazette, July 1796.

Salem Gazette, July 1796. .

.

The Tabernacle Church of 1777-1854, from Samuel Worcester’s Memorial of the Old and New Tabernacle (1855); payments to Daniel Bancroft in the Tabernacle Church administrative

The Tabernacle Church of 1777-1854, from Samuel Worcester’s Memorial of the Old and New Tabernacle (1855); payments to Daniel Bancroft in the Tabernacle Church administrative

Is the Red Line going to take us across North Street to the beautiful Peirce-Nichols House? Of course not, sharp left to the Witch House, after we’ve just been to the Witch Dungeon Museum.

Is the Red Line going to take us across North Street to the beautiful Peirce-Nichols House? Of course not, sharp left to the Witch House, after we’ve just been to the Witch Dungeon Museum. Two empty courthouses downtown: can’t ONE play a key public role?

Two empty courthouses downtown: can’t ONE play a key public role?

Thank goodness for Wicked Good Books and the Hotel Salem, otherwise there’s not a lot going on on the Essex Street pedestrian mall, day or night.

Thank goodness for Wicked Good Books and the Hotel Salem, otherwise there’s not a lot going on on the Essex Street pedestrian mall, day or night.

Bridge Street Neck was not “home to a large population of African Americans” in the 19th century: just check the city directories!

Bridge Street Neck was not “home to a large population of African Americans” in the 19th century: just check the city directories!