I was up in New Hampshire this past weekend for a spectacular summer wedding on Dublin Lake, and of course I made time for side trips; the Granite State continues to be a place of perpetual discovery for me after a lifetime of merely driving around or through it, to and from a succession of homes in Vermont, Maine and Massachusetts. On the day before the wedding, some friends and I drove north to see The Fells, the Lake Sunapee home of John Milton Hay (1838-1905), who served in the administrations of Presidents Lincoln, McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt. Hay is the perfect example of a dedicated public servant and statesman, attending to President Lincoln as his private secretary until the very end, at his deathbed, and dying in office (at The Fells) while serving as President Roosevelt’s Secretary of State. He was also a distinguished diplomat, poet, and a key biographer of Lincoln. Fulfilling the conservation mission that was a key part of his purchase and development of the lakeside property, Hay’s descendants donated the extended acreage surrounding the house to the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests and the US Fish and Wildlife Service in the 1960s, and it eventually became the John Hay National Wildlife Refuge. Hay’s daughter-in-law Alice Hay maintained the house as her summer residence until her death in 1987, after which it was established as a non-profit organization, open for visitors from Memorial Day through Columbus Day weekends.

When it comes to nineteenth- and early twentieth-century country or summer residences in New England which are now open to the public, it seems to me there are three essential types: those of very rich people (think Newport), those of statesmen (The Fells; Hildene in Manchester, Vermont; Naumkeag in Stockbridge), and those of creative people (The Mount in Lenox; Beauport; Aspet, Augustus Saint-Gauden’s summer home and studio in Cornish, New Hampshire). The last category is my favorite by far, but there’s always lots to learn by visiting the houses of the rich and the connected, and John Milton Hay was as connected as they come. I was a bit underwhelmed by the house, which is a Colonial Revival amalgamation of two earlier structures, until I got to its second floor, which has lovely views of the lake and surrounding acreage plus a distinct family feel created by smaller interconnected bedrooms opening up into a long central hall. The airiness of the first floor felt a bit institutional, but this was an estate built for a very public man, after all. For the Hays, I think it was all about the relation of the house to its setting, rather than the house itself.

The gardens surrounding the house also seemed a bit sparse although it was a hot day in late July and we might be between blooms; certainly the foundations and structures are there, especially in the rock garden that leads down to the lake. This was the passion of Hay’s youngest son, Clarence, who established the garden in 1920 and worked on it throughout his life. After his death in 1969, the garden was lost to forest, but it was reestablished by the efforts of the Friends of the Hay Wildlife Refuge and the Garden Conservancy. When you’re standing in the rock garden looking up at the house, or in the second floor of the house looking down at the rock garden and the lake beyond, you can understand why the well-connected and well-traveled John Milton Hay proclaimed that “nowhere have I found a more beautiful spot” in 1890.

Essex Street, 1918-1927(including a new Novalux light decorating for Christmas), the Hawthorne Hotel, 1926 (showcasing streetlight AND stoplight) and Bridge Street, General Electric Company Archives, MiSci: the Museum of Innovation and Science.

Essex Street, 1918-1927(including a new Novalux light decorating for Christmas), the Hawthorne Hotel, 1926 (showcasing streetlight AND stoplight) and Bridge Street, General Electric Company Archives, MiSci: the Museum of Innovation and Science.

Lafayette Street, the intersection at West, Loring, and Lafayette, and (I think???) the road to Marblehead.

Lafayette Street, the intersection at West, Loring, and Lafayette, and (I think???) the road to Marblehead.

Interior Lighting at the Almy, Bigelow & Washburn and William G. Webber stores on Essex Street.

Interior Lighting at the Almy, Bigelow & Washburn and William G. Webber stores on Essex Street.

Washington Street during World War I: the new Masonic Temple building and the illuminated war chest; floodlights at a trapshooting competition somewhere in Salem.

Washington Street during World War I: the new Masonic Temple building and the illuminated war chest; floodlights at a trapshooting competition somewhere in Salem.

The last photograph of the last Tsar, Nicholas II, and his family, at the Ipatiev House in Yekaterinburg, where they were executed in the early hours of July 17, 1918.

The last photograph of the last Tsar, Nicholas II, and his family, at the Ipatiev House in Yekaterinburg, where they were executed in the early hours of July 17, 1918.

Summer Street from Broad with the Doyle Mansion on the right, Frank Cousins

Summer Street from Broad with the Doyle Mansion on the right, Frank Cousins

Views of the exterior and interior of the Doyle Mansion by Frank Cousins, collection of glass plate negatives at the Phillips Library of the Peabody Essex Museum, Digital Commonwealth.

Views of the exterior and interior of the Doyle Mansion by Frank Cousins, collection of glass plate negatives at the Phillips Library of the Peabody Essex Museum, Digital Commonwealth.

Boston Globe, June 1934; the Holyoke Mutual Fire Insurance building, built in 1936 and now owned by Common Ground Enterprises (and its rather weedy sidewalk!)

Boston Globe, June 1934; the Holyoke Mutual Fire Insurance building, built in 1936 and now owned by Common Ground Enterprises (and its rather weedy sidewalk!)

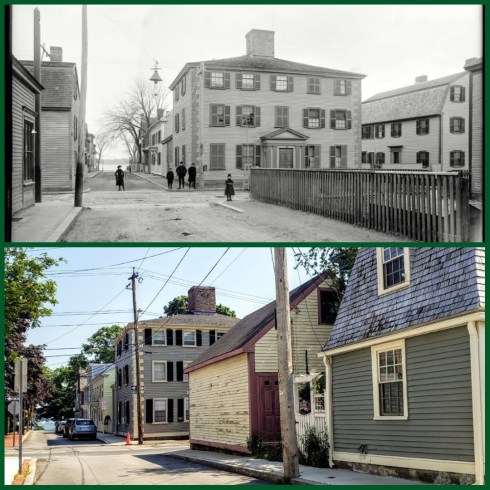

The John P. Felt House on Federal Court past and present: despite a rough last half-century or so, the house is still standing in good form, lacking only its widow’s walk and shutters.

The John P. Felt House on Federal Court past and present: despite a rough last half-century or so, the house is still standing in good form, lacking only its widow’s walk and shutters. Barton Square has been pretty much annihilated.

Barton Square has been pretty much annihilated. Change and continuity on Bott’s Court: old house on the left, newer (both 1890s) houses on the right. Cousins is showing us the demolition of the former house on the right with his preservationist eye.

Change and continuity on Bott’s Court: old house on the left, newer (both 1890s) houses on the right. Cousins is showing us the demolition of the former house on the right with his preservationist eye. Kimball Court present and past: Cousins is showing us the birthplace of Nathaniel Bowditch below: this house is in the top right corner above. In front of it today is a house that was brought over from Church Street during urban renewal in the 1960s when that street was wiped out.

Kimball Court present and past: Cousins is showing us the birthplace of Nathaniel Bowditch below: this house is in the top right corner above. In front of it today is a house that was brought over from Church Street during urban renewal in the 1960s when that street was wiped out. 18 Lynde Street: this appears to be the same house, with major doorway changes.

18 Lynde Street: this appears to be the same house, with major doorway changes. The house on Mall Street where Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote the Scarlet Letter: there was an addition attached to the house at some point in the 1980s or thereabouts.

The house on Mall Street where Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote the Scarlet Letter: there was an addition attached to the house at some point in the 1980s or thereabouts. 134 Bridge Street: As a major entrance corridor–then and now—Bridge Street has impacted by car traffic pretty dramatically over the twentieth century; Cousins portrays a sleepier street with some great houses, many of which are still standing—hopefully the progressive sweep of vinyl along this street will stop soon.

134 Bridge Street: As a major entrance corridor–then and now—Bridge Street has impacted by car traffic pretty dramatically over the twentieth century; Cousins portrays a sleepier street with some great houses, many of which are still standing—hopefully the progressive sweep of vinyl along this street will stop soon. 17 Pickman Street seems to have acquired a more distinguished entrance; this was the former Mack Industrial School (Cousins’ caption reads “Hack” incorrectly).

17 Pickman Street seems to have acquired a more distinguished entrance; this was the former Mack Industrial School (Cousins’ caption reads “Hack” incorrectly). Great view of lower Daniels Street–leading down to Salem Harbor–and the house built for Captain Nathaniel Silsbee (Senior) in 1783. You can’t tell because of the trees, but the roofline of this house has been much altered, along with its entrance.

Great view of lower Daniels Street–leading down to Salem Harbor–and the house built for Captain Nathaniel Silsbee (Senior) in 1783. You can’t tell because of the trees, but the roofline of this house has been much altered, along with its entrance. Hardy Street, 1890s and today: with the “mansion house” of Captain Edward Allen still standing proudly on Derby Street though somewhat obstructed by this particular view. You can read a very comprehensive history of this house

Hardy Street, 1890s and today: with the “mansion house” of Captain Edward Allen still standing proudly on Derby Street though somewhat obstructed by this particular view. You can read a very comprehensive history of this house