The 1920s was a decade of intensive commemoration in Massachusetts, in recognition of the 300th anniversaries of the landing at Plymouth in 1620 and the arrival of John Winthrop here in Salem in 1630, bearing the royal charter that formally recognized the Massachusetts Bay Company. The commemoration culminated with the formation of the Massachusetts Bay Colony Tercentennial Commission in 1929, which oversaw thousands of events, including processions, pageants, historical exercises, old home weeks, exhibitions and expositions, the publication of various commemorative materials like Massachusetts on the Sea and Pathways of the Puritans, and the erection of roadside historical markers across the Commonwealth (the Salem markers are all “missing”—I’m coming to the unfortunate conclusion that there has been a long cumulative campaign to remove as much of Salem’s tangible history as possible, with the relocation of the Phillips Library as the end game! Maybe we are cursed–or maybe I’ve lost my perspective).

Smithsonian/National Postal Museum

There was also some sort of map initiative: as I’ve found several pictorial/historical maps–of the commonwealth, various regions, and individual towns–published in this period, often by the Tudor Press and under the auspices (and with the approval) of the Tercentenary Conference of City and Town Committees. Elizabeth Shurtleff’s Map of Massachusetts. The Old Bay State (which is in the Phillips Library but fortunately also in David Rumsey’s vast digital collection) is one such map, and there are others representing Cape Cod, Cape Ann, Boston, and several other Massachusetts towns and cities. As you can see from the cropped images of James Fagan’s map of Shawmut/Boston 1630-1930 and Coulton Waugh’s map of Cape Ann and the North Shore, these maps were “historical” in an extremely subjective way, emphasizing achievements above all. As explicitly stated by Fagan, they pictorialize progress above all. I’m sure that this message was particularly important given the coincidental timing of the Massachusetts Tercentenary and the onset of the Great Depression.

So far, I’ve seen 1930 pictorial/historical maps of Ipswich, Concord, Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, Cambridge, and the other day, while looking for something altogether different in the digital collections of the Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library, I came across of one of Salem! Very exciting–I thought I had chased down every Salem map in existence but no, there was (is) The Port of Salem, Massachusetts by Warren H. Butler, published by the Tudor Press in 1930. This is a perfect Colonial Revival map really, focused on recreating a rather whimsical/historical “olde” Salem rather than tracing the path of progress. I love it, even though my own house seems to have been swallowed up by an extended Hamilton Hall on lower Chestnut Street. It’s hard to date this map: in the accompanying text, Butler says “here are the ancient streets of Salem”, but while the streets depicted seem to be vaguely Colonial, the buildings that line these streets are of varying periods. His Salem is a port city first and foremost, but while he includes ships in both the harbor and North River and Front Street is really Front Street, the massive Gothic Revival train station is here too. Samuel McIntire’s courthouse is located in its historic location on Washington Street, just a few steps from the Greek Revival courthouse that still stands, vacant, in Salem. All of the Derby houses are on the map, including the majestic–and ephemeral—McIntire mansion which once sat in the midst of present-day Derby Square. In fact all of my favorite Salem houses, still-standing and long gone, are on Butler’s map: it’s a historio-fantasy map of non-Witch City, and I want to go there!

You can zoom in on Salem’s “ancient” streets yourself at the BPL’s Leventhal Map Center.

You can zoom in on Salem’s “ancient” streets yourself at the BPL’s Leventhal Map Center.

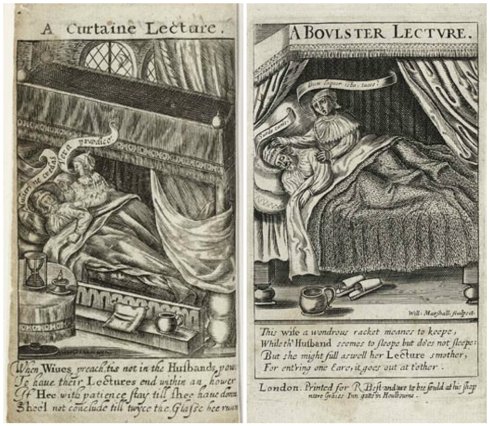

A Curtain Lecture pub. by J. Lewis Marks, 1824, British Museum; illustrations by John Leech for the first edition of Mrs. Caudle’s Curtain Lectures, 1845; Mrs. Caudle Card (with real hair!), Victoria & Albert Museum; 1907 stereoview from the Library of Congress; postcards, c. 1900-1910.

A Curtain Lecture pub. by J. Lewis Marks, 1824, British Museum; illustrations by John Leech for the first edition of Mrs. Caudle’s Curtain Lectures, 1845; Mrs. Caudle Card (with real hair!), Victoria & Albert Museum; 1907 stereoview from the Library of Congress; postcards, c. 1900-1910. Compare the PEM’s online

Compare the PEM’s online

The very interesting house of Edward Sylvester Morse on Linden Street in Salem; the Account Book of the Thomas Perkins of Salem (pictured above from the Essex Institute’s Old-Time Ships of Salem, 1922) is included in Adam Matthew’s China, America, and Pacific database.

The very interesting house of Edward Sylvester Morse on Linden Street in Salem; the Account Book of the Thomas Perkins of Salem (pictured above from the Essex Institute’s Old-Time Ships of Salem, 1922) is included in Adam Matthew’s China, America, and Pacific database. The interior of the East India Marine Hall past and present, and before the installation of the PEM’s newest

The interior of the East India Marine Hall past and present, and before the installation of the PEM’s newest

The Collections of the Essex Institute in the Phillips Library Reading Room, 1980, and the library collections reinstalled, 2008,

The Collections of the Essex Institute in the Phillips Library Reading Room, 1980, and the library collections reinstalled, 2008,

And I really fear I’ll be too reliant on the detailed-yet-romantic work of Maine-born architect Frank E. Wallis, whose reverence for Salem is all too apparent! Plates from Frank E. Wallis,

And I really fear I’ll be too reliant on the detailed-yet-romantic work of Maine-born architect Frank E. Wallis, whose reverence for Salem is all too apparent! Plates from Frank E. Wallis,

Mr. Monroe at the PEM forum last night.

Mr. Monroe at the PEM forum last night. The shuttered Phillips Library.

The shuttered Phillips Library.

Flyer for the 1/11 forum, position letter of newly-revived “Friends of Salem’s Phillips Library”(which is so new that it is homeless but I think it is going to wind up

Flyer for the 1/11 forum, position letter of newly-revived “Friends of Salem’s Phillips Library”(which is so new that it is homeless but I think it is going to wind up  One of my very favorite photographs from the Phillips collections that I’ve found while DREDGING every and all online sources this month: from the anniversary of the Children’s Friends & Family Services, Inc. (Phillips MSS 447), 1839-2003, which began life as the Salem Seamen’s Orphan Society and has 54 boxes of records on deposit in the Phillips.

One of my very favorite photographs from the Phillips collections that I’ve found while DREDGING every and all online sources this month: from the anniversary of the Children’s Friends & Family Services, Inc. (Phillips MSS 447), 1839-2003, which began life as the Salem Seamen’s Orphan Society and has 54 boxes of records on deposit in the Phillips.

British soldier Leonard Knight and the bullet-ridden

British soldier Leonard Knight and the bullet-ridden

Chestnut and Essex Streets above; below, a panorama of Derby Wharf at high tide which was passed around by a bunch of architects yesterday, but I think can be attributed to ©Kirt Rieder. Beautiful but scary!

Chestnut and Essex Streets above; below, a panorama of Derby Wharf at high tide which was passed around by a bunch of architects yesterday, but I think can be attributed to ©Kirt Rieder. Beautiful but scary!