I often get asked if I’m ever going to write a book about Salem—and I always feel like the subtext of the question is or are you just going to keep dabbling on your blog? I always say no, as I’m not really interested in producing any sort of popular history about Salem and I’m not a trained American historian. I have a few academic projects I’m working on now and at the same time I like to indulge my curiosity about the environment in which I live, because, frankly, most of the books that do get published on Salem’s history tend to tell the same story time and time again. First Period architecture is the one topic that tempts me to go deeper: not architectural history per se (again, another field in which I am not trained), but more the social and cultural history of Salem’s seventeenth-century structures—especially those that survived into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. How do they change over time? Why do some get preserved and others demolished? What was their perceived value, at any given time? Why do some houses get turned into memorials/museums/”monuments” and others disappear, forever forgotten? And (here’s the blogging angle): why are some of these structures preserved for posterity in photographic and artistic form and others not? This is a rather long-winded contextual introduction to my focus today: the wonderful house renderings of the Anglo-American artist Edwin Whitefield (1816-1892). Whitefield was an extremely prolific painter of landscapes and streetscapes, flora and fauna, and I’m mentioned him here several times before, but I recently acquired my own copy of one of his Homes of our Forefathers volumes, and now I need to wax poetic. I just love his pencil-and-paint First Period houses: they are detailed yet impressionistic, simple yet structural, and completely charming. I can’t get enough of them.

There are five Homes of our Forefathers volumes, published between 1879 and 1889, covering all of New England and a bit of Old England as well: Boston and Massachusetts are intensively covered in several volumes. Whitefield clearly saw himself as a visual recorder of these buildings and was recognized as such at the time (a time when many of these structures were doubtless threatened): An 1889 Boston Journal review of his houses remarked that “We cannot easily exaggerate the service which Mr. Whitefield has rendered in preserving them”. Even though the title pages advertised “original drawings made on the spot”, implying immediate impressions, Whitefield put considerable research and detail in his drawings, intentionally removing modern alterations and additions so that they were indeed the homes of our forefathers. His process and intent are key to understanding why Whitefield includes some structures in his volumes and omits others. He includes only two little-known Salem structures in Homes: the Palmer House, which stood on High Street Court, and the Prince House, which was situated on the Common, near the intersection of Washington Square South, East and Forrester Street. There were so many other First Period houses in Salem that he could have included–Pickering, Shattuck, Ruck, Gedney, Narbonne, Corwin, Turner-Ingersoll–but instead he chose two houses which were much more obscure, thus rescuing them from perpetual obscurity.

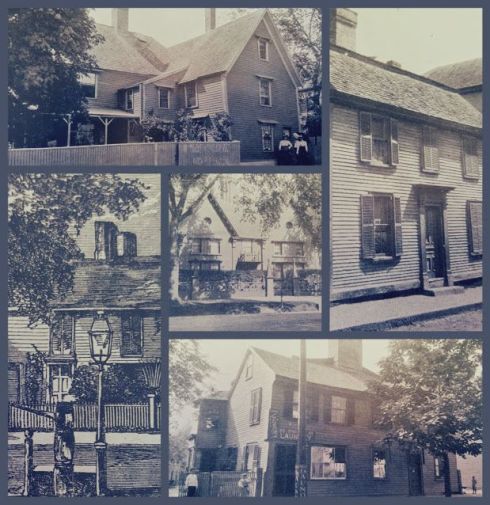

Already-famous First Period houses in Salem, either because of their Hawthorne, witchcraft, or Revolutionary associations: the Turner-Ingersoll house before it was transformed into the House of the Seven Gables, Hawthorne’s birthplace in its original situation, the Shattuck House on Essex Street, a sketch of the Corwin “Witch House” and the Pickering House. Whitefield’s single postcard of the Witch House in its original incarnation (it was then thought to be the residence of Roger Williams, an association that was later disproven by Sidney Perley).

The Palmer and Prince houses are mentioned in the Pickering Genealogy (Palmer) and Perley’s Essex Antiquarian articles, and apparently there’s a photograph of the former deep in the archives of the Phillips Library, but without Whitefield’s sketches they wouldn’t exist. He was drawn to them, I think, by both their age and their vulnerability: both would be torn down, with little notice, in the same decade that his sketches were published.

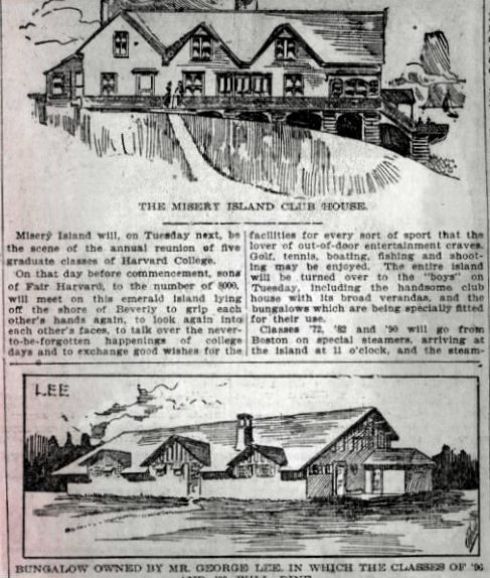

Newspaper reports of the 1902 Harvard reunions (Boston Post, June 22-25, 1902 ) and 1926 fire (Boston Daily Globe, May 8-10, 1926); Great Misery today, and home in Salem Harbor on a glorious early evening!

Newspaper reports of the 1902 Harvard reunions (Boston Post, June 22-25, 1902 ) and 1926 fire (Boston Daily Globe, May 8-10, 1926); Great Misery today, and home in Salem Harbor on a glorious early evening!

Just one of my many copies of the invaluable Old Salem Gardens (1947) with the Chase garden entry; the location of the Chase garden on the 1874 and 1891 Salem Atlases.

Just one of my many copies of the invaluable Old Salem Gardens (1947) with the Chase garden entry; the location of the Chase garden on the 1874 and 1891 Salem Atlases.

Views of the front and back of the Chase Garden (including Mr. Chase himself on the bench), 1904, Archives of American Gardens, Smithsonian Institution; Ten years later on Lafayette Street: postcard views of the Fire’s immediate aftermath from the (commemorative???) Views of Salem after the Great Fire of June 25, 1914 brochure issued by the New England Stationery Company.

Views of the front and back of the Chase Garden (including Mr. Chase himself on the bench), 1904, Archives of American Gardens, Smithsonian Institution; Ten years later on Lafayette Street: postcard views of the Fire’s immediate aftermath from the (commemorative???) Views of Salem after the Great Fire of June 25, 1914 brochure issued by the New England Stationery Company.

Just one weekend in Salem: The Salem Award Foundation’s 25th Anniversary Celebration and Salem’s Trials Symposium. Below, the Witch Trials Memorial off Charter Street, yesterday: for much less contemplative times, click

Just one weekend in Salem: The Salem Award Foundation’s 25th Anniversary Celebration and Salem’s Trials Symposium. Below, the Witch Trials Memorial off Charter Street, yesterday: for much less contemplative times, click

19th Century Reverse-Painted Ship Silhouette on Glass Maple Frame, circa 1840, Trinity Antiques & Interiors,

19th Century Reverse-Painted Ship Silhouette on Glass Maple Frame, circa 1840, Trinity Antiques & Interiors,

Michele Felice Corné’s Perseverance Wrecked (1805), and a portrait of Captain Richard Wheatland by the Chinese artist

Michele Felice Corné’s Perseverance Wrecked (1805), and a portrait of Captain Richard Wheatland by the Chinese artist

H.M.S.

H.M.S.