I had yet another “symbol trauma” (I have no other way to refer to it) on Friday when people starting sending me images of little anime cats with notes indicating that this was the new official mascot for Salem’s 400th commemoration, Salem 400+. Was this a joke? Apparently not. Here’s the press release text and the cat (in front of 1910 City Hall just to emphasize his/her official status).

Mayor Dominick Pangallo has announced an exciting new community engagment opportunity: a naming context for Salem 400+’s black cat mascot! Salem 400+ has unveiled a charming black cat character designed to strengthen the program’s connection with the community and celebrate Salem’s unique identity. Salem students in 3d through 8th grade have been invited to participate in naming this special mascot through a district-wide contest that opened a few weeks ago. “There was so much positive community spirit and creativity when it came to naming our new trash truck, Chicken Nugget, we wanted to open up this opportunity to our students as well, said Mayor Pangallo, “the Salem 400+ black cat will help represent Salem and this special moment, and we want our young students to be part of bringing it to life.”

So of course engaging students in a naming contest is great but I’m sorry: the choice of this AI anime cat is not. He (or she—we don’t know yet!) is everything that Salem is not: superficial, generic, silly, not serious. I understand the political reality here (the Chicken Nugget roll-out was intense—it was very clear that whoever got in between the trash truck and a Salem politician was in trouble if photographers were nearby), but I’m just so tired of the triviality. There are always these gestures in Salem that go 3/4 of the way but never all the way: a Remond Park with incorrect information about where Salem’s 19th century African American residents actually lived, a Forten Park which loses Charlotte between gaudy installations and pirate murals. But this is a whole new dimension of dissing Salem history. Even my long-suffering husband, who has to hear me rant nearly every day, said wow. There’s nothing anyone can do but disengage, so when I woke up Saturday morning, I knew I had to get out of town. Fortunately it was a grand weekend of Revolutionary remembrance in Essex County, so up to Newburyport I went. It happened that this was the 250th anniversary of Benedict Arnold’s Quebec Expedition, in which Newburport played a large role. So I headed north, because even Benedict Arnold looked good to me.

The Quebec Expedition (I think the first poster is rather old) was a spectacular failure. With the new Continental Army ensconced in Cambridge, Colonel Arnold approached General Washington with the idea of an eastern invasion force aimed at Quebec City in concert with General Richard Montgomery’s western expedition from New York. Washington gave Arnold 1110 men, who sailed from Newburyport on September 19, 1775. Their destination was the mouth of the Kennebec River, from which they would progress upriver to Fort Western (Augusta, ME) after which they would navigate water, marsh and land to the Chaudiere and St. Lawrence Rivers and Quebec. They encountered so many difficulties along the way that ultimately a quarter of the regiment turned back (taking essential provisions with them), and Arnold arrived in Quebec with 600+ exhausted and starving men. A New Year’s Eve battle was a disastrous defeat, resulting in the death of General Montgomery, the injury of Arnold, and the capture of Captain Daniel Morgan and hundreds of his riflemen. Nevertheless, Arnold was promoted to Brigadier General for his leadership of the expedition. The weekend’s activities were definitely focused on Newburyport’s “early and ardent embrace of the Revolutionary cause” rather than on Arnold himself.

Everywhere I went in Newburyport and adjoining Newbury I ran into people engaged in their history: the celebration of a new plaque recognizing the patriots of Newburyport at the Old South Church (above), a parade of participants making their way down High Street following a reenactment of the 1775 dedication for departing troops at the nearby First Parish Church, glanced from the doorway of Historic New England’s Swett–Ilsley House after the guide and I paused our tour. The Museum of Old Newbury set out its revolutionary artifacts in the rooms of its 1808 Cushing House, including a reconstructed Newburyport rum jug taken out of the ground in shards amidst the “Great Carrying Place,” a 13-mile portage trail between the Kennebec and Dead Rivers through which Arnold and his men passed 250 years ago. Actually, the jug was on a brief loan to the Museum from the Arnold Expedition Historical Society and Old Fort Western Museum and Executive Director Bethany Groff Dorau drove up to Maine to retrieve it for just this commemorative weekend., but the Museum is full of its own treasures and I’ve featured just a few of my favorites below. I’m looking forward to going back, and back again.

Rooms and Collections at the Swett-Ilsley and Cushing Houses in Newbury and Newburyport: that’s a portrait of Lafayette leading into the south parlor at Cushing—what a punch they made for him when he visited in 1824! And I am obsessed with the c. 1786 portrait of the Reverend John Murray by Christian Gullager. Great Liverpool jugs! The Museum is the historical sociey of Newbury, Newburyport, and West Newbury, so its collections are vast and varied.

And on the way home, I encountered a handtub muster on Newbury upper common! What could be better? Just a perfect day away.

Detail from Jan Wildens, Panoramic View of the City of Antwerp across the River Scheldt, 1630.

Detail from Jan Wildens, Panoramic View of the City of Antwerp across the River Scheldt, 1630.

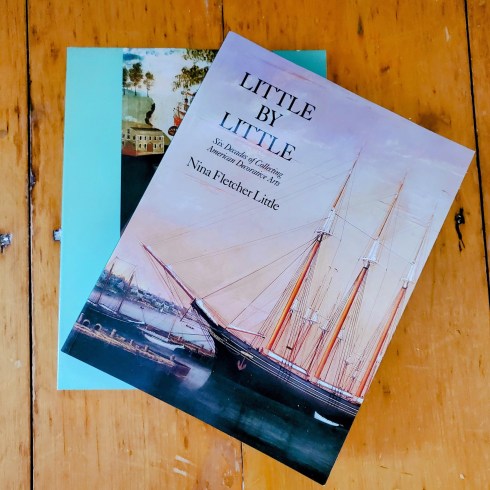

A front parlor and Mrs. Little’s charming closet office.

A front parlor and Mrs. Little’s charming closet office.

The open hearth kitchen/dining room and various halls of objects. An anonymous couple in their finery by Royall Brewster Smith, c. 1830.

The open hearth kitchen/dining room and various halls of objects. An anonymous couple in their finery by Royall Brewster Smith, c. 1830.

Mr. Gould in his red cap; second-floor parlor and bedrooms; an amazing pictorial collage of the arrival of the first Oddfellows in America (there they are in the bottom left corner!); the BIG barn.

Mr. Gould in his red cap; second-floor parlor and bedrooms; an amazing pictorial collage of the arrival of the first Oddfellows in America (there they are in the bottom left corner!); the BIG barn.

The Sensational Sidney brothers as boys: Sir Philip and Sir Robert, from a painting by Mark Garrard at the Sidney’s ancestral home Penshurst Palace, Kent.

The Sensational Sidney brothers as boys: Sir Philip and Sir Robert, from a painting by Mark Garrard at the Sidney’s ancestral home Penshurst Palace, Kent.

Sir Philip Sidney, 1577-78, courtesy the Marquess of Bath, Longleat House; A trio of Sidney copied portraits from the sixteenth, eighteenth, and twentieth centuries: National Portrait Gallery, London; an 18th century copy, NPG, London, and a 20th century version attributed to Frederick Hawkesworth Sinclair, Pembroke College, Oxford University.

Sir Philip Sidney, 1577-78, courtesy the Marquess of Bath, Longleat House; A trio of Sidney copied portraits from the sixteenth, eighteenth, and twentieth centuries: National Portrait Gallery, London; an 18th century copy, NPG, London, and a 20th century version attributed to Frederick Hawkesworth Sinclair, Pembroke College, Oxford University.

Sir Philip Sidney, early 17th century, National Trust @Knole; by John de Critz the Elder, c. 1620; by John de Critz the Elder, 17th century; by George Knapton, 1739.

Sir Philip Sidney, early 17th century, National Trust @Knole; by John de Critz the Elder, c. 1620; by John de Critz the Elder, 17th century; by George Knapton, 1739. Portrait of Captain Thomas Lee by Marcus Gheeraerts II, 1594,

Portrait of Captain Thomas Lee by Marcus Gheeraerts II, 1594,