So I was going to bring you some photographs of Salem during yesterday’s snowstorm today, but that would have necessitated actually going out and walking around, and just a few steps from my backyard out onto Chestnut Street at midday were enough to convince me that I didn’t want to do that. So I have images of snowstorms past, mostly new discoveries, and most from the Peabody Essex Museum’s Phillips Library, which possesses the largest collection of famed photographers Frank Cousins and Samuel Chamberlain, as well as images by amateur photographers in family papers. True to their promises of several years ago, the Phillips librarians have been steadily digitizing their local collections and everytime I go their digital collections page I see new-to-me things. If you’re new to Salem photo-sleuthing, you can just start with their very accessible “Salem Streets” collection, culled from a variety of sources. And of course all the glass plate negatives of Frank Cousins were digitized quite a while ago, and can also be found at Digital Commonwealth. My title is from Cousins, who assembled several of his favorite images for an 1891 collage, which I imagine was hung in the window of his Bee-Hive shop that very winter. Then I’m going to double back and proceed in chronological order.

So let’s go back a decade into the 1880s, when we really start to see a lot of photographs of Salem streets and buildings, both commercially published and popping up in family papers. I’ll never forget opening up the volumes of the Francis Lee papers a few summers ago at the Phillips Library in Rowley and seeing all of these gorgeous photographs from the mid-1880s. The photos below are from the same time period—1884-86—and this first amazing one is taken from the vantage point of Lee’s house, 14 Chestnut Street. No filter! Isn’t this a striking image? This photo and those that follow are attributed to John Robinson, a Salem author and horticulturalist and trustee of pretty much every single civic institution in the city at the time. I wasn’t aware that he was a photographer as well; I don’t know if had commissioned these images for some future publication? The last one of this group is from the vantage point of his house on Summer Street, and so we have two striking views of Samuel McIntire’s South Church, which burned to the ground in 1903.

Chestnut Street winters, Salem Streets collection, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.

The 1890s: was Frank Cousins’ most productive decade as a photographer. He loved to photograph Chestnut Street too, but he branched out, all over the city, as his “Frosty Salem” poster illustrates. I love his winter shots because many of them include people, while his more formal architectural photographs decidedly do not.

Essex Street, the Common, Dearborn and Lafayette Streets,1890s, Frank Cousins Glass Plate Negative Collection, Phillips Library via Digital Commonwealth.

Also from the 1890s are several photographs by amateur photographers of an uprooted (Elm?) tree on Chestnut Street, with every possible angle captured! I have looked in vain for more views of dealing with the snow, but this is as close as I could get. Closing out this decade are several beautiful photographs of the Pickering and Bartlett houses on Broad Street which are somehow connected to (taken by?) a certain Katherine A. Pond. I need to know more about her.

Chestnut and Broad Streets, 1890s, Phillips Library Digital Collections.

The 1920s: when I was looking for photos of Salem’s 1926 Tercentenary in various family albums at the Phillips, I came across the photos of the winter of 1924-25 in Francis Tuckerman Parker’s album. Again, these are not professional, and they are not digitized—I just took photos of the snapshots myself—so they not that great quality, but they are so interesting for what they show. The first image shows the intersection of Chestnut, Summer, and Norman Streets and on the extreme right is what I think is the last photograph of Samuel McIntire’s house before its demolition. The second, looking up Chestunt in the other direction, shows the church that replaced McIntire’s South Church, which was later demolished. Then we have a snow trolley on Essex, and a very messy intersection at the Essex and Summer.

Salem in the winter of 1924-25, Parker Family Photograph Album, Phillips Library.

1930s: the Phillips Library also possesses the huge negative collection of Samuel Chamberlain, a very important mid-century photographer of New England architecture and scenery, which is accessible at Digital Commonwealth. Chamberlain published Historic Salem in Four Seasons in 1938, so I assume these photos are from that time, but the collection encompasses his entire career. Pioneer Village, Salem’s outdoor living-history museum, was in its first decade, and Chamberlain photographed its buildings and landscape lavishly.

Pioneer Village by Samuel Chamberlain, Digital Commonwealth.

And finally, a street view of Broad Street in 1956 and an aerial view of Chestnut in 1972, both after the storms. The latter is included in a feature in Life magazine in that year, prompted by President Nixon’s visit to China. Eastern-oriented Salem seemed like a good place to examine American perspectives on Asia at that time; I don’t think that would be the first Salem association now.

Salem in 1956 and 1972: William F. Abbott collection at the Phillips Library and Life magazine, 1972.

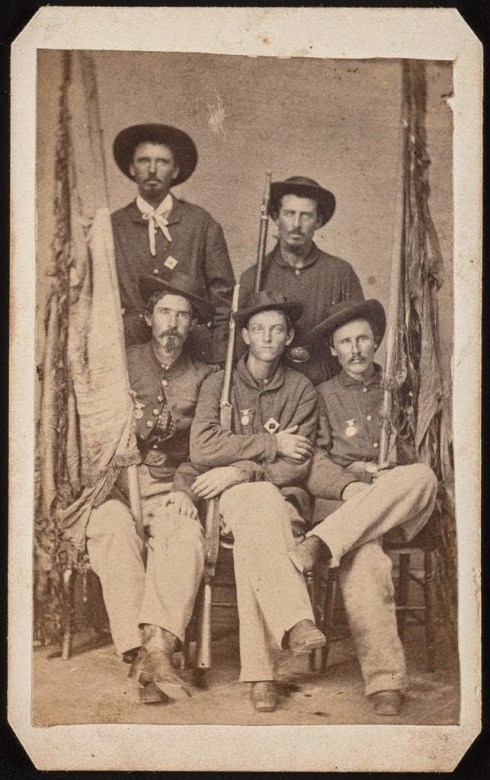

Phillips Library PHA 67 & 151.

Phillips Library PHA 67 & 151.

Chestnut, Summer & Norman Streets from two perspectives. I’ll never get over how wonderful Norman Street was!

Chestnut, Summer & Norman Streets from two perspectives. I’ll never get over how wonderful Norman Street was!

Riding and looking north on Summer Street, and then south (Samuel McIntire’s house is on the extreme left of the last photograph).

Riding and looking north on Summer Street, and then south (Samuel McIntire’s house is on the extreme left of the last photograph). Broad Street, looking west.

Broad Street, looking west.

Cambridge Street, looking north and south.

Cambridge Street, looking north and south. Work on Bott’s Court.

Work on Bott’s Court. Hamilton Street, looking north.

Hamilton Street, looking north.

Chestnut Street Houses—what’s going on with that figure at the third-floor level of the third photo above, which I think is #26?

Chestnut Street Houses—what’s going on with that figure at the third-floor level of the third photo above, which I think is #26? Warren Street, looking towards the “Turnpike” (Highland Avenue).

Warren Street, looking towards the “Turnpike” (Highland Avenue).

This doesn’t line up perfectly, but what a great restoration +addition by Salem architect Oscar Padjen: very representative of the creativity of “Plan B”!

This doesn’t line up perfectly, but what a great restoration +addition by Salem architect Oscar Padjen: very representative of the creativity of “Plan B”!