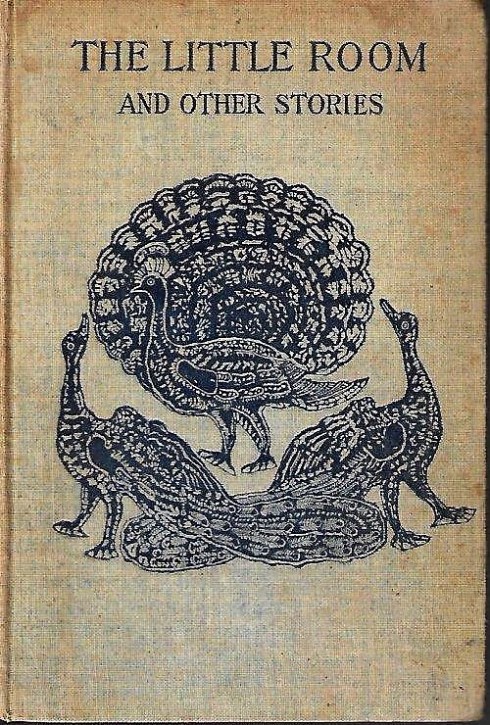

My mind is whirling these days: we’re at the end of the semester, and a teaching-free summer lies ahead of me, but so do three writing projects, maybe more. I’m always thinking, but I’m also really tired, so it’s not all constructive. Thankfully gardening season has begun, but I did not feel particularly re-energized after my first foray out back last weekend—just sore! Then I remembered this book that I picked up down in Connecticut during our stay at the Griswold Inn a few weeks ago. The Griswold has no televisions in their rooms, which pleased me, but not my husband, so I suggested we go to a rather elegant used bookstore next door. We browsed, he more intently than I, but I came across a beautiful book that I thought I could add to my bedside stack of books I never read because I seem to only read for information, and all my informational books are in my study. I bought it, threw it in my suitcase, brought it home and forgot all about it until this past Sunday, when I poured myself a glass of wine and opened it up………….and immediately began to relax, in the best possible, almost entranced way. This book is entitled At Home. The American Family 1750-1870, and it was written by Elisabeth Donaghy Garrett (now Widmer), then (1990) a vice-president at Sotheby’s, and author of several books on historic interiors. Apparently Ms. Garrett had published a series of articles on “the American Home” in The Magazine Antiques in 1983 that was so well-received that it prompted the publication of this book and boy, I can understand why. Peter Thornton, whose book Authentic Decor: the Domestic Interior 1620-1920 I am familiar with, notes in his Forward that the “outstanding quality” of At Home is “the sheer weight of evidence that has been marshaled and the manner in which it has all been presented.” I agree, but I think the manner is more important, at least for my personal purposes: I seldom read for pleasure, and this book offered both pure pleasure and tons of information, in well-crafted text and well-curated pictures. It really took me away, and that never happens.

I really wanted this book to be a picture book, a coffee table book, which I could just breeze through from time to time. And I suppose it is that, if you want it to be. The illustrations are amazing, representing a full-spectrum of deep-hued oils from well-known American artists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, to seldom-seen (at least by me) watercolors of domestic scenes sourced from local historical societies. But once I started reading, I couldn’t stop: Garrett is a wonderful writer who favors narrative and literary sources, so her text is quite lively, and as Thornton observed, she manages to integrate a lot of information in a very accessible manner. I could take a lesson from her, but I’d rather just enjoy her book. The chapters begin with individual rooms in the house (their uses and all about their furnishings, in great detail) and then proceed to the myriad elements and tasks that go into making a home, all year round, and in the city and the country. So we have: parlors, the dining room, the kitchen, the bedchambers, lighting, “the daily dog-trot routine of domestic duties,” “the quest for comfort,” (probably my favorite chapter–a lot of heating and cooling advice, and bugs!), the tribulations of the early American housewife, and husband and wife as consumers. Here are some of my favorite images, and a few notes about how Garrett used them: I tend toward the vernacular, because so many of the paintings and prints in this book were new to me, but there are plenty of formal interior scenes as well. Since we’re in the beautiful month of May, I’m also going to focus primarily on summer homes: cozy parlors can come later.

The Children of Nathan Comfort Starr, Middletown, CT by Ambrose Andrews, 1855, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Garrett notes the elevation of the house, designed to promote healthy air inside. This looks like a happy scene of children playing shuttlecock, but Garrett believes that it is a memorial painting of the youngest son (in the dress, of course) who died when he was just over a year old.

York, Pennsylvania Family, 1828, anonymous artist, St. Louis Museum of Art. At Home is just as much about households as houses, including servants. Garrett discusses servants but she does not discuss race. This is a book of its time (1990), which is before the renewed historiographical focus on the roles of African-Americans in the northern US. She includes three images of African-Americans in the corners or the margins, but she does not digress on their identity or position beyond that of “trusted servants.” At Home is a study in material culture, not a social history, and so this painting is used to describe the vivid wallpaper and carpet (boy does this book have a lot to say about carpets!) contrasted with the simple painted furniture.

Rhode Island Interior by an anonymous artist, 1800-1810, collection of Fenton Brown. It’s really all about the carpets! They demanded so much time, and money. Women (or their servants) pulled them up in the spring, nailed them down in the fall, and spent a lot time worrying about moths. Garrett uses this particular image to present a European gaze on American interiors, which she does often throughout her book. An Italian observer noted that Americans “displayed few pictures, statues, or ornamented furniture, preferring instead mahogany furniture and fine carpets.”

Two paintings by Massachusetts artist Ellla Emory of Peter Cushing House in Hingham, MA: East Chamber and Old Laundry, c. 1878, both Private Collection. I love this artist! Back to the floors: this sisal-like straw matting was very popular in the summer for centuries—one of my favorite paintings of the Elizabethan court shows the same covering! Floors could be bare in the back of the house, and in hallways as well, and beach sand was spread around.

Garrett includes quite a few watercolors by new-to-me New Bedford artist Joseph Shoemaker Russell (1795–1860), all of which I found absolutely charming. Russell painted New England interiors, but spent some time in Philadelphia too, where he captured all the rooms of his boarding house: above are Mrs. A.W. Smith’s Parlor and Mrs. J.S. Russell’s Room at Mrs. A.W. Smith’s, both 1853 and in private collections. These are summer views, and present opportunities for Garrett to discuss shutters in detail, as well as the necessity of closing up the fireplace with fireboards or flowers during the warm months. The parlor view shows a gas-fed lamp of the 1850s, and also the American custom (noted by all of Garrett’s European sources) of placing all the furniture along the walls of the room. Silhouettes are everywhere in this book!

More summer images (and challenges): View from the House of Henry Briscoe Thomas, Baltimore, by an anomynous artist, c. 1841, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Tea, Alexandria by William Marshall Merrick, 1860, New York Public Library. Come Spring, the lady of the house (or her servants) had to change not only the carpet, but also the draperies. If she didn’t have shutters, she had to pull down the heavy drapes and replace with sheers. She (or her servants) also had to drag all the furniture outside for an airing: Spring cleaning was a really big deal. The battle against bugs intensified with the warm weather, but it was really fought all year long, the principal enemies being flies, mosquitoes, moths and bedbugs.

Ice Cart by Nicolino Calyo, c. 1840-44, New-York Historical Society. The provisioning of the household also varies with the seasons, and “the ice-cart was an integral part of the iconography of summer in the city” from May until October. The New England re-export ice trade was an Atlantic affair, and Garrett’s European observers frequently commented on the abundance of ice in American households.

Now refreshed: I can attack the (digital) pile of final papers and examinations before me!

Like this:

Like Loading...