I have posted about green quite a bit on this blog: green cards, green men, green rooms, the green fairy, my favorite shade of green. Yet it’s St. Patrick’s Day, so I’ve got to come up with something green–why not the emotion associated with the emerald hue? Shakespeare was specifically referring to jealousy with Othello’s “green-eyed monster” line, but jealousy is just a subset of the more all-encompassing envy, one of the seven deadly sins and the one conspicuous for its complete lack of pleasure: it leads not to material wealth or power or drunkenness, but only to a festering illness in which one literally eats their heart out. This self-inflicted sickness–described as a form of moral rotting–could be one source of the sin’s connection with the color green, as could its association with snakes, either alone or in the form of an allegorical Medusa-like character, but emerald (or chartreuse) envy seems to be more of a modern conception than a medieval one.

Michael Craig-Martin, Envy (from the Seven Deadly Sins series), 2008. Tate Modern, London.

Medieval manuscripts illustrate envy (invidia) in several ways: on the iconic “Tree of Vices”, accompanied by a demon and its “sprouts” (detraction, treachery, treason, homicide, conniving, pleasure in the suffering of others–what we would call Schadenfreude–resentment, jealousy) and as a woman looking at something or someone with daggers (sometimes literally). Pride is always the root of the tree–the root all the vices– but envy is just one branch up from the fall of Man. Pride, represented by a King-like character riding a lion, and Envy, a sword-bearing woman riding a wolf, are closely associated in the fifteenth-century edition of penitential psalms below, and Envy reveals her jealous nature in a fourteenth-century Roman de la Rose. Green is not her color, yet.

The Apocalypse of St. John, c. 1420-30, Wellcome Library, London; British Library MS Yates Thompson 3, c. 1440-1450, and MS Royal 19BXIII, the Roman de la Rose of Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun, c. 1320-1340.

Beginning with Giotto, the Renaissance shifted Envy decisively towards jealousy and generally portrayed her as an aged woman, tearing at her heart and/or eating an apple to illustrate her complete capitulation to temptation, often grotesque and emaciated, clearly suffering and sometimes chained, almost always with snakes. There’s a rather striking similarity between the depictions of Envy and witches in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, before the conception of envy in particular and the seven deadly sins in general become secularized. A notable exception is Hieronymus Bosch’s famous table painting, The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things, which depicts envy with an illustration of a local proverb about two dogs with one bone seldom reaching agreement. Still no green.

Giotto di Bondone, Envy panel from the Arena Chapel, 1306; Print by George Pencz, 1541, British Museum; Hieronymus Bosch, The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things detail, c. 1485.

Looking through allegorical images of envy from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, I still don’t see much green, but then again, prints predominate. Lots of snakes are in appearance, which is appropriate for a St. Patrick’s Day post as the cleansing of Ireland of snakes is part of St. Patrick’s mythology. At least the connection between women and this most miserable sin is broken, as envy appears in the form of both sexes and then only as a green snake.

Print by John Goddard, c. 1640, British Museum; “Envy” (perhaps a caricature of the Earl of Abingdon), Anonymous, 1796, British Museum.

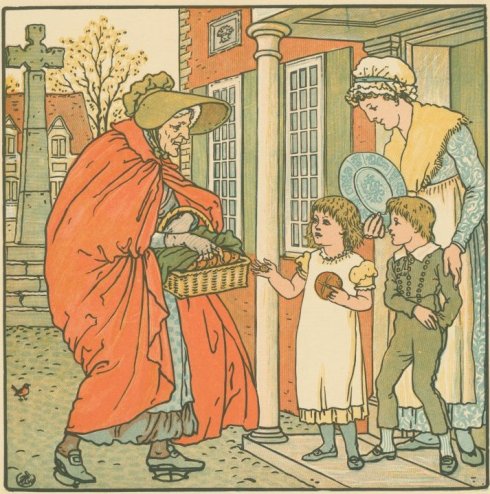

Envy is depicted in all sorts of ways by modern artists and illustrators, though the aged-lady-turning-green (grotesque)-with envy certainly comes back with a vengeance! I don’t usually see things exclusively through the prism of gender, but it’s really interesting to me how this most self-destructive of sins is so often associated with women. In two twentieth-century Seven Deadly Sins series, the Belgian artist James Sensor envisions a christening in which the young mother (interestingly dressed in green) is looked on with envy by everyone around her, but by the middle-aged woman to her right with particular vehemence, and Paul Cadmus’s Envy definitely harkens back to the Renaissance. As before, envy does not make for a pretty picture; I think I prefer alternative associations for the color green!

James Ensor, L’Envie, from the 1904 portfolio The Deadly Sins, Art Institute of Chicago; Paul Cadmus, The Seven Deadly Sins: Envy, 1947, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Like this:

Like Loading...