It’s been interesting to see scores of religious commentators draw comparisons to Pope Benedict XVI’s resignation (effective later today) and that of the next-to-last Pope to resign, the briefly-reigning St. Celestine V, who served for five months in 1294. Celestine’s renunciation is indeed a much better comparison than that of Gregory XII, whose 1415 abdication was coerced by the power politics of the Western Schism, for a number of reasons. Even though the two popes are separated by the centuries and their records of service to the Church, they might have been of like mind in their mutual desire to retreat from the very worldly powers and obligations of their office.

Celestine V: British Library MS Harley 1340, attributed to Joachim of Fiore, mid-fifteenth century.

In his statement of renunciation, Benedict expressed his desire “to also devotedly serve the Holy Church of God in the future through a life dedicated to prayer”, which was also the stated goal of his predecessor, who went further: “I Celestine V, moved by valid reasons, that is, by humility, by desire of a better life, by a troubled conscience, troubles of body, a lack of knowledge, personal shortcomings, and so that I may proceed to a life of greater humility, voluntarily and without compunction give up the papacy and renounce its position and dignity, burdens and honors, with full freedom”.

These men were roughly the same (advanced) age, so I am certain that “troubles of body” have a lot to do with both of their abdications. And they were both reluctant Popes, Celestine even more so than Benedict. The so-called “hermit-Pope” was the founder of an order of friars that bore his pontifical name, and he was more comfortable in their company than in Rome. While the reactions to Pope Benedict’s resignation strike me as largely positive, this was not the case with Celestine’s: he was labeled cowardly, a characterization that was reinforced by Dante’s Inferno, which refers to the shade of him who in his cowardice made the great refusal. Dante’s anger derives from his hatred of Celestine’s successor, Boniface VIII, who many believed manipulated “the great refusal”.

The Liber Sextus: Sextus decretalium liber a Bonifacio viii in concilio Lugdunensi editus (Venice: Luca Antonio Giunta, 1514), Courtesy Lillian Goldman Library, Yale Law School. Boniface’s foxy fox is pulling the papal tiara off Celestine’s head, while the holy dove flies above the latter’s head.

Among his contemporaries, there were those who also admired Celestine’s retreat from the world, and he was canonized in 1313 for his piety. During the Schism and after, when the Church was perceived as being corrupt and over-worldly,Celestine and his renunciation were increasingly depicted in a more positive light, both by theologians and artists, who depicted the resigned Pope as the very image of humility, in the plain grey robes of his order with the papal tiara in his hand (or on the ground) rather than on his head.

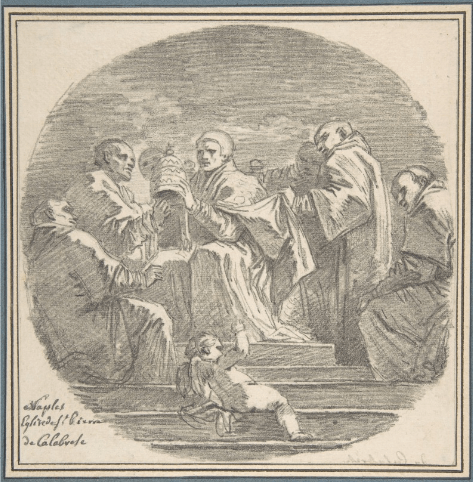

St. Celestine, the hermit-Pope; Jean Honoré Fragonard, Saint Celestine V Renouncing the Papacy after Mattia Preti, 1761. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Beyond the label Popes who quit, there are a few more connections between Celestine V and Benedict XVI. After the devastating L’Aquila earthquake in 2009, the present (just) Pope visited the Abruzzo region, from where Celestine hails and where he is venerated as a saint. The purpose of Benedict’s visit was clearly to comfort the inhabitants of the region in the wake of the quake, but while he was there he also made a point of visiting sites associated with Celestine, including his tomb (miraculously intact in the midst of the severely-damaged Basilica Santa Maria di Collemaggio in Aquila), where he left his inaugural pallium (a vestment, or “stole of honor” and symbol of papal authority), apparently a gesture of great significance. A year later, to mark the 800th anniversary of Celestine’s birth, Pope Benedict visited his reliquary at nearby Sulmona Cathedral, towards the end of his proclaimed “Celestine Year”. This is reverential treatment of a retreated Pope, by one who is now retreating himself.

Benedict XVI and Celestine V, 2009. Associated Press/Boston Herald.