We have eight fireplaces and six mantles in our house, and because I seem to be inextricably tied to the rule that a mantle must have a mirror over it, I’m always on the hunt for the elusively perfect mirror. It’s a rather casual hunt, as I have mirrors for all my mantels, just not the right mirrors. Right now, I’m on the lookout for a carved oval gilt mirror from the first half of the nineteenth century, a search that began when I spotted this Salem-made, circa 1820 mirror on ARTstor.

It’s a bit flamboyant but I love it and wish I could find out more about it; I think it would be a whimsical counter-piece to the more sedate and square mirrors that I already have. But of course it’s not for sale, and if it were it would probably cost as much as the house. There’s a somewhat similar oval mirror on 1stdibs from Jorgenson Antiques, but second mortgages must go towards structural necessities rather than decorative accessories!

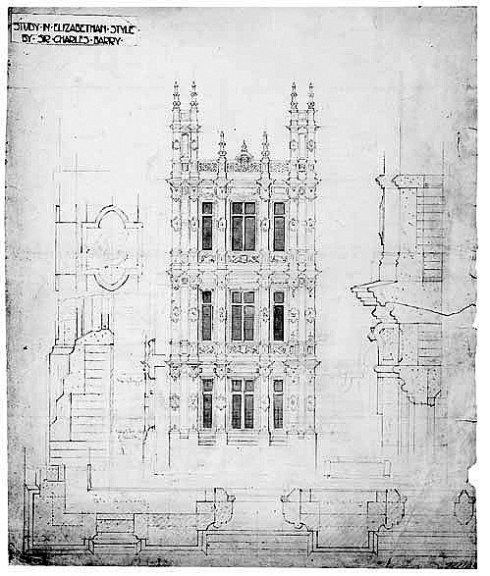

Here are some other mirrors in the unattainable mirror files, starting with an elaborate oval overmantle mirror in the Cook-Oliver House here in Salem: it takes a particularly impressive mirror to grace a McIntire-carved mantle. And then, in no particular order, a Chippendale design for an overmantle mirror dated 1765, another design drawing for a horizontal oval mirror by James Wyatt from the same era (maybe all I want is drawing of a fancy mirror), and a watercolor of a Warwick Castle bedroom from a charming book of plates entitled Historic English Interiors (Hessling, New York, 1920).

I thought I was looking for an oval mirror until I came across this picture of Ben Bradlee’s and Sally Quinn’s Georgetown dining room: the embellished rectangular mirror is really lovely, especially over that mantle and against that paper–reproduced from a pattern that was in Mr. Bradlee’s mother’s home in New England. He descends from the Salem Crowninshields, which might be how and why he was in possession of 12 McIntire chairs. What you see below are copies; he donated the originals to the White House.