I had not thought about the prolific and pioneering author Harriet Martineau (1802-1876) for years: until I encountered a portrait of her by the Salem artist Charles Osgood in the Catalog of Portraits at the Essex Institute (1936). I was looking for some lost portraits of Salem women—portraits which are still presumably in the collection of the Peabody Essex Museum but which we have no access to either digitally or in person, and for which no accessible catalog entry exists except in the Smithsonian’s Catalog of American Portraits. I found many such portraits in this catalog, but I did not expect to find Harriet, a popular British author whose many works contributed to the emerging fields of sociology, economics, and political science. Martineau was cast into the breadwinner role for her impoverished family while in her 20s, and so she picked up a pen and produced an astonishing array of texts illustrating the contemporary social and economic structures of the British Empire: taxation, the poor laws, industry and trade. While these might seem like dry topics then and now, Martineau had an extraordinary ability to interpret, translate, and distill abstract and complex theory into clear and engaging prose: both Charles Darwin and Queen Victoria were fans! Travels to the United States and the Middle East expanded Martineau’s range of topics as well as her abilities to report and observe, and she moved beyond illustration and theory into methodology, thus contributing to social-science practice. Martineau accepted no limitations: of genre (she wrote both fiction and non-fiction) or gender, and neither her encroaching deafness or her many illnesses stopped her from writing. When diagnosed with fatal heart disease in 1855, she wrote her own obituary, noting that: Her original power was nothing more than was due to earnestness and intellectual clearness within a certain range. With small imaginative and suggestive powers, and therefore nothing approaching to genius, she could see clearly what she did see, and give a clear expression to what she had to say. In short, she could popularize while she could neither discover nor invent. She lived, and wrote, for another twenty years.

Harriet Martineau by Salem artist Charles Osgood, c. 1835, Catalog of Portraits in the Essex Institute (1936); and by Richard Evans, c. 1833-34, National Portrait Gallery.

Harriet Martineau by Salem artist Charles Osgood, c. 1835, Catalog of Portraits in the Essex Institute (1936); and by Richard Evans, c. 1833-34, National Portrait Gallery.

In 1834, the same year that her Evans portrait was exhibited in London, Harriet traveled to the United States on a research trip: she wanted to observe and analyze the dynamic economy of the new nation, as well as its “peculiar institution” of slavery. Her time in America refined her observation skills but also made her more of an activist: encountering both slavery in the south and the fervent abolitionist community in New England intensified her own anti-slavery sentiments. She published her American observations in Society in America (1837) which contains a forceful critique of the Southern economy’s exclusive reliance on slave labor and a much more favorable view of New England based on principles of the “moral economy”. In the Slave South, “one of the absolutely inevitable results of slaver is a disregard of human rights; an inability even to comprehend them”, while in the egalitarian North “every man is answerable for his own fortunes; and there is therefore stimulus to the exercise of every power.” Martineau goes on to extol the economic (and social) virtues of Salem, where she was in residence for several weeks at the Chestnut Street home of Congressman (and future mayor) Stephen C. Phillips. She loves everything about Salem: its beautiful historic homes, its bustling tanneries, its “famous” museum, but especially its social mobility: “what a state of society it is when a dozen artisans of one town—Salem—are seen rearing each a comfortable one-story (or, as the Americans would say, two-story) house, in the place with which they have grown up! when a man who began with laying bricks criticizes, and sometimes corrects, his lawyer’s composition; when a poor errand-boy becomes the proprietor of a flourishing store, before he is thirty; pays off the capital advanced by his friends at the rate of 2,000 dollars per month; and bids fair to be one of the most substantial citizens of the place!”

Salem in the mid-nineteenth century from John Bachelder’s Album of New England Scenery.

Salem in the mid-nineteenth century from John Bachelder’s Album of New England Scenery.

Harriet Martineau was far more interested in the present than the past, and she predicts that the “remarkable” Salem, “this city of peace”, “will be better known hereafter for its commerce than for its witch-tragedy.” [if only!!!] Nevertheless, it happens that both one of her earliest and one of her last American publications was focused on Salem witchcraft: reviews of Charles Wentworth Upham’s Lectures on Witchcraft comprising a history of the delusion in Salem, in 1692 (1831) and Salem Witchcraft with an account of Salem Village and a history of opinions on Witchcraft and Kindred Subjects (1867). Her review of the latter in the Edinburgh Review displays her interpretive abilities perfectly, managing to both summarize Upham’s work and supplement it with a Victorian sensibility as well as the perspective of a social scientist. Like many of her contemporaries, Martineau was interested in psychological experimentation: the practice of mesmerism, in particular, was interesting to her for its curative powers as she experienced challenging medical conditions from the 1840s. Her interest in the powers of suggestion influenced her reaction to Upham’s study of the Salem trials, but so too did her sociological studies of organized religion and community interactions. She manages to display both historical empathy and the presentism which characterizes so many interpretations of the Salem Witch Trials at the same time as she emphasized “the seriousness and the instructiveness of this story to the present generation [this could have been written today]. Ours is the generation which has seen the spread of Spiritualism in Europe and America, a phenomenon which deprives us of all right to treat the Salem Tragedy as a jest, or to adopt a tone of superiority in compassion for the agents in that dismal drama.” [this could not].

The first Upham work to be reviewed by Harriet, and a sketch of Miss Martineau at work in Fraser’s Magazine, November, 1833.

The first Upham work to be reviewed by Harriet, and a sketch of Miss Martineau at work in Fraser’s Magazine, November, 1833.

The 1906 graduating class of the Salem Normal School

The 1906 graduating class of the Salem Normal School

Advertisements in the Salem Gazette and Register, 1821-1853: Cambric and Bombazine dresses from MoMu: Fashion Museum Antwerp and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Advertisements in the Salem Gazette and Register, 1821-1853: Cambric and Bombazine dresses from MoMu: Fashion Museum Antwerp and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Salem Register, January & July 1862; South Peabody Wizard, January 1869; Newburyport Daily Herald, November 1886.

Salem Register, January & July 1862; South Peabody Wizard, January 1869; Newburyport Daily Herald, November 1886.

The President’s wedding from Harper’s Weekly, June 12, 1886 via the Library of Congress. Mrs. Endicott is on the extreme left above.

The President’s wedding from Harper’s Weekly, June 12, 1886 via the Library of Congress. Mrs. Endicott is on the extreme left above. Mrs. Endicott’s houses: clockwise, Washington Square and Essex Street, Salem; 163 Marlborough Street, the Farm (Glen Magna).

Mrs. Endicott’s houses: clockwise, Washington Square and Essex Street, Salem; 163 Marlborough Street, the Farm (Glen Magna).

William Crowninshield’s death in May of 1901 was a national headline; Ellen Peabody Endicott (Mrs. William Crowninshield Endicott), 1901 by John Singer Sargent,

William Crowninshield’s death in May of 1901 was a national headline; Ellen Peabody Endicott (Mrs. William Crowninshield Endicott), 1901 by John Singer Sargent,

Boston Post 13 February 1903

Boston Post 13 February 1903

Fidelia Bridges (1834-1923) by Oliver Ingraham Lay, 1872, Smithsonian: Bridges is probably the first and most successful Salem woman artist, though she traveled widely and lived in Connecticut for most of her professional life.

Fidelia Bridges (1834-1923) by Oliver Ingraham Lay, 1872, Smithsonian: Bridges is probably the first and most successful Salem woman artist, though she traveled widely and lived in Connecticut for most of her professional life.

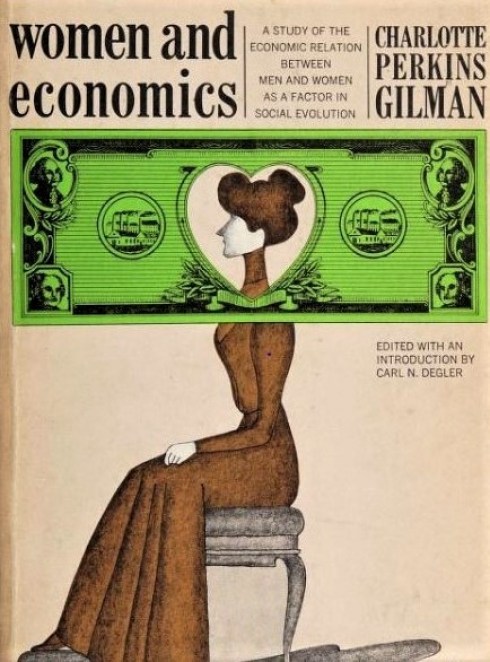

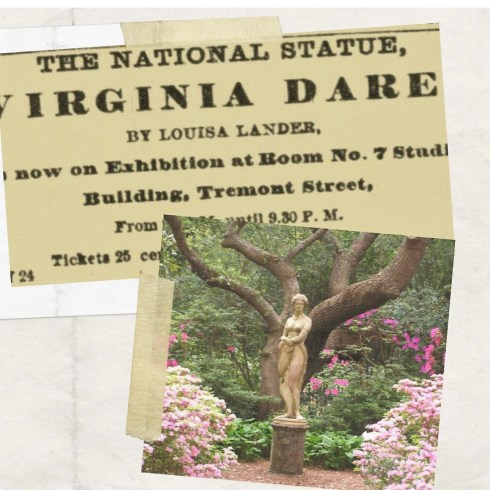

Mary E. Williams, illustrations from The Hours of Raphael in Outline – Together with the Ceiling of the Hall Where They Were Originally Painted (Little, Brown, 1891); Just some of Mary and Abigail Williams’ works shown in the 1875 Essex Institute Exhibition; Virginia Dare in the Elizabethan Gardens & notice in the Boston Post, January 24, 1865.

Mary E. Williams, illustrations from The Hours of Raphael in Outline – Together with the Ceiling of the Hall Where They Were Originally Painted (Little, Brown, 1891); Just some of Mary and Abigail Williams’ works shown in the 1875 Essex Institute Exhibition; Virginia Dare in the Elizabethan Gardens & notice in the Boston Post, January 24, 1865.

Betty Ring’s two-volume Girlhood Embroidery; Salem samplers by Susannah Saunders (Sothebys) and Elizabeth Crowinshield (Doyles); Jenny Brooks Co. advertisements from 1913, and Mary Saltonstall Parker’s cover embroidery for House Beautiful, October 1916.

Betty Ring’s two-volume Girlhood Embroidery; Salem samplers by Susannah Saunders (Sothebys) and Elizabeth Crowinshield (Doyles); Jenny Brooks Co. advertisements from 1913, and Mary Saltonstall Parker’s cover embroidery for House Beautiful, October 1916. Sarah Symonds in her studio, Phillips MSS 0.202, Papers of Sarah Symonds, 1912-21.

Sarah Symonds in her studio, Phillips MSS 0.202, Papers of Sarah Symonds, 1912-21.

©Julie Shaw Lutts, The Vote.

©Julie Shaw Lutts, The Vote. Samantha is currently wearing an ensemble by local artist Jacob Belair, which I think is lovely on its own but also because it covers part of her up! I wish it extended to her unfortunate pedestal. I’m not in Salem now, so I asked my stepson ©Allen Seger to take the photos of Samantha in crochet.

Samantha is currently wearing an ensemble by local artist Jacob Belair, which I think is lovely on its own but also because it covers part of her up! I wish it extended to her unfortunate pedestal. I’m not in Salem now, so I asked my stepson ©Allen Seger to take the photos of Samantha in crochet.

The Boston Women’s Memorial by Meredith Bergmann; photographs from her

The Boston Women’s Memorial by Meredith Bergmann; photographs from her

Model and Mock-up of the first and final monument to the Women’s Rights Pioneers by Sculptor Meredith Bergmann, to be unveiled in Central Park on August 26, 2020.

Model and Mock-up of the first and final monument to the Women’s Rights Pioneers by Sculptor Meredith Bergmann, to be unveiled in Central Park on August 26, 2020.

The Knoxville and Nashville Suffrage statues—both by Tennessee sculptor Alan LeQuire—and the unveiling of seven statues of prominent Virginia women last fall: former Virginia First Lady Susan Allen points to a statue of Elizabeth Keckley, dressmaker for Mary Todd Lincoln, and suffragist Adele Clark among the crowds (Bob Brown/ Richmond Times-Dispatch).

The Knoxville and Nashville Suffrage statues—both by Tennessee sculptor Alan LeQuire—and the unveiling of seven statues of prominent Virginia women last fall: former Virginia First Lady Susan Allen points to a statue of Elizabeth Keckley, dressmaker for Mary Todd Lincoln, and suffragist Adele Clark among the crowds (Bob Brown/ Richmond Times-Dispatch).

The Anthony-Stanton-Bloomer statue (1998) by Ted Aub in Seneca Falls; Ira Srole’s “Let’s Have Tea” (2009) in Rochester.

The Anthony-Stanton-Bloomer statue (1998) by Ted Aub in Seneca Falls; Ira Srole’s “Let’s Have Tea” (2009) in Rochester. Office of the Architect of the Capitol.

Office of the Architect of the Capitol.