I am not fond of blue-and-white china (or anything blue, to tell you the truth), nor do I particularly like the Willow pattern, one of the most popular and replicated in the western world for several centuries. But I do love both the idea and the act of updating something that is classically familiar—even overly familiar–in a clever and creative way. So when I saw a little story about Calamityware, in which flying monkeys and flying saucers, along with robots and Renaissance sea creatures, are right there on the plate along with the traditional “Chinese” structures, figures, and landscapes, I went right to the source: artist Don Moyer’s site, on which his earlier drawings are coming to life (or pottery) on a Kickstarter-funded production line. So many things about these plates appeal to me (despite their color): they are blatantly anachronistic, purely whimsical, and perfect examples of my favorite fusion of past and present, traditional and modern, new and old. The flying monkeys were first off the line, and we may see kings and oligarchs later, though surely they won’t be as scary.

Calamityware is not the first variation on the Blue Willow pattern; in fact it was inspirational almost from its inception–and wildly popular. I’ve got a bowl full of Willow shards uncovered in my back yard when I was digging out my herb garden. Willow ware was first produced in the late eighteenth century by Thomas Minton, an English potter who adapted designs featured on Chinese export porcelain for domestic production. There was no patent protection, and his competitors–Wedgwood, Royal Worcester, Spode–began producing their own Blue Willow, and continued to do so for the next two centuries. In an early stroke of advertising genius, a story was composed to sell the dishes: when a powerful Chinese lord discovers that his daughter has fallen in love with his lowly clerk, he locks her up in a secluded pagoda behind a fence and betrothes her to a rich and elderly duke. The young couple flee before the wedding, but are hunted down and killed (there are different versions of their deaths). True love prevails, however, as the gods transform the lovers into a pair of lovebirds which remain together forever, hovering above the willow tree that once shaded their clandestine meetings. The story expanded the reach of Blue Willow–beyond the pottery business and into popular culture: poems, books, textiles, and pictures told the Blue Willow love story over and over again in the Victorian era, and after.

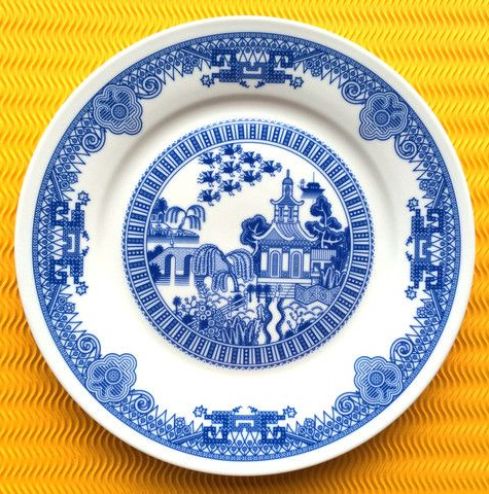

Spode Blue Willow plate, c. 1800-1820, Victoria & Albert Museum; Joyce Mercer (1896-1965) illustration, 1920s.

And now, Willow ware seems to be having a moment, once again. In fact, this “moment” seems to encompass the past decade or so, or perhaps the pattern, in all of its variations (and colors–I could go for the red), is always having a moment. And that, of course, is the definition of classic. In 2005 ceramicist Robert Dawson digitally-designed a line of “After Willow” dishes for Wedgwood, and more recently we have Pokemon Willow by Olly Moss (note the lovebirds, still flying above!) and there are more calamities to come.

May 29th, 2014 at 9:16 am

I wonder why 99% of them are only blue? All red would have been nice.

May 29th, 2014 at 10:36 am

They do use other colors in the 19th century, Mark, and even multiple colors–but the original Chinese export ware was blue and white–and the European copies in the 17th and 18th century–so that’s where the primary demand was.