Rather contrarily, my offering for Mother’s Day weekend is not a warm, loving, and lovely caregiver but a prophesying crone: Mother Shipton, who most likely never existed. Supposedly born in the first years of the new Tudor dynasty in a Yorkshire cave (the product of a union between a poor wretch named Agatha and the Devil), Ursula Southeil or “Mother Shipton” rose to fame in the mid-seventeenth century, long after her supposed death. Just before the English Civil War, a time of high anxiety indeed, a series of Mother Shipton pamphlets suddenly appeared, containing predictions of things that, for the most part, had already happened, along with dire warnings of war and destruction.

The first prophecy on the second 1642 pamphlet is typical Mother Shipton: Joane Waller should live to heare of Wars within this Kingdome but not to see them. The Civil War broke out in the same year of as the tract was published, but of course Waller had died the year before. A similar assertion regarding Henry VIII’s chief minister, Cardinal Wolsey, that he would see York but never get there, was one of Mother Shipton’s most famous “predictions”. Her published prophecies continued through the Civil War (closely tied to current events) and after, and she joined the ranks of such legendary magicians as Merlin.

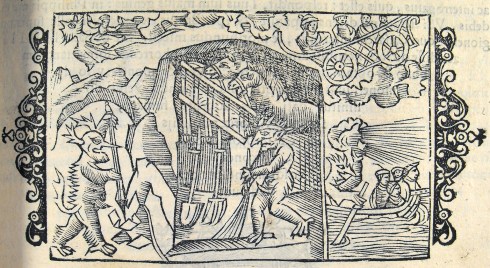

Shipton Prophecies from 1648 & 1661

In the later seventeenth century, Mother Shipton’s biography and predictions were embellished rather vastly by a series of publications entitled The Life and Death of Mother Shipton, and her story was adapted for entertainment purposes, thus cementing her now-legendary character. The transition from ominous witch-soothsayer to stock character is emblematic of the emergence of a collective rationalist mentality in the seventeenth century, with a corresponding decline in belief in magic and “wonder”, now assuming its more modern meaning.

And that would probably be the end of Mother Shipton, consigned to a relatively minor character in the long history of sibyls and soothsayers, if she was not resurrected in the Victorian era. It’s always the Victorians! Charles Dickens first referenced her in a 1856 story, and then the entrepreneurial bookseller Charles Hindley published a new set of rhymed and timely prophecies that were supposedly based on a newly-discovered manuscript in the British Museum (he later confessed to making them up). Now Mother Shipton was predicting railroads, ships made of iron, wireless communication and all sorts of industrial innovations, as well as the ominous warning that the world then to an end shall come/ In Eighteen Hundred and Eighty-One, which was changed to 1991 in early-twentieth-century reprints. By that time, she had evolved yet again, into a fairy-tale character and (later) a tourist attraction.

Charles Townley print of Mother Shipton and her familiar, 1800, British Museum, Linley Sanbourne and W. Heath Robinson illustrations of Mother Shipton on her broomstick for Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies. A Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby (1888 & 1915); the entrance to Mother Shipton’s Cave in Knaresborough, “England’s Oldest Tourist Attraction” (shades of Salem!).