Distillation became an important household activity for many women in early modern Europe in the seventeenth century; we have ample evidence that they wrote, purchased, collected, annotated, and shared recipes for medicinal, hygienic, and sweet-smelling waters and spirits. I’m sure it was the same on this side of the Atlantic as well: indeed, the “secrets” of distillation might have been even more valued as opportunities to purchase ready-make substances were more limited. This is a big topic in women’s history, at the intersection of women’s work and domestic life. There are three ways to get into it: the prescriptive way, through popular printed books on distillation, the archival way, through extant written collections of recipes, and the ephemeral way, through advertisements by women who were producing distilled spirits for sale—this latter entry is more of an eighteenth-century window. Recipe-rich resources for the distilling activities (or goals) of English women in the early modern era are pretty ample: but do we have any evidence of distilling activities among women here in Salem?

Distillation is one of the “Accomplished Lady’s” (or her servant’s) responsibilities on the title page of Hannah Woolley’s Accomplished Lady’s Delight, 1684, Folger Shakespeare Library; inset of the frontispiece to The Accomplished Ladies Rich Cabinet of Rarities, 1691, Wellcome Library; Recipe for a classic cordial, Orange Water, in the Folger Shakespeare Library’s MS V.a.669, c. 1680.

Distillation is one of the “Accomplished Lady’s” (or her servant’s) responsibilities on the title page of Hannah Woolley’s Accomplished Lady’s Delight, 1684, Folger Shakespeare Library; inset of the frontispiece to The Accomplished Ladies Rich Cabinet of Rarities, 1691, Wellcome Library; Recipe for a classic cordial, Orange Water, in the Folger Shakespeare Library’s MS V.a.669, c. 1680.

I went through the Phillips Library’s Finding Aids and couldn’t find the kind of domestic journals I’ve seen kept by English women, which include general household account books and more specialized recipe books or some combination of both, but there is a presentation on Elizabeth Corwin’s household book next week so that might be an opportunity to learn more about a Salem woman’s domestic economic life in the seventeenth century. That left me with advertisements, and I did find two in which Salem women were selling distilled spirits, both of the medicinal kind and the alcoholic kind. Before I get to Anna Jones and Eunice Richardson, however, a word (or several) about the evolution of these spirits. Distilled waters start to appear in the later fifteenth century in England, and are generally referred to as “cordials” as their primary purpose was to invigorate the heart and thus one’s spirits: depending on the recipe, other waters were designated “surfeit” and prescribed for indigestion. By about 1700 or so, it’s clear that these waters are being consumed for pleasure as well as their perceived medicinal virtues. The line between medicine and merriment was fuzzy: aqua-vitae, for example, is a term used for a strong and pleasant drink, generally brandy, but was also an ingredient in several medicinal “spirits”. That said, the two Salem women who entered into this business—or carried on their husbands’ businesses—represent two sides of the distilling spectrum in the later eighteenth century.

Salem Gazette, 1770,1772,1796.

Salem Gazette, 1770,1772,1796.

Anna Jones was clearly a small-time distiller, carrying on her husband’s business on Charter Street in the 1770s: the recipes for all of those cordial waters, with the exception of snake-root (an American plant), go all the way back to Tudor times. These were medicinals, but I’m sure they were pleasant to drink too! Mrs. Richardson, by contrast, was a purveyor rather than a distiller herself: rum was a much bigger business and was not made in the backroom stillroom (45 hogsheads!). The two big spirits of the eighteenth century, gin and rum, had no recognized medicinal virtues and thus the line between domestic medicinal distilling and commercial distillation became more sharply drawn in the later eighteenth century: Anna Jones and Eunice Richardson represent either side in Salem.

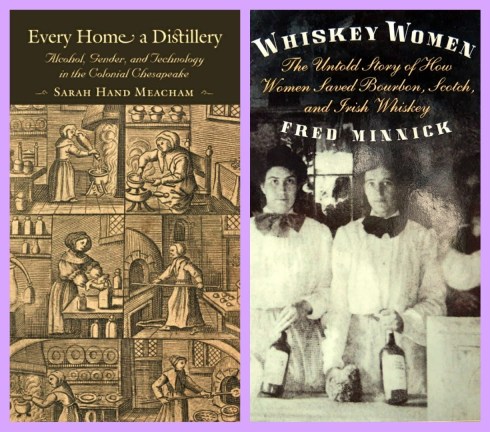

A seventeenth-century stillhouse, and two recent books on distilling women: domestic and commercial.

A seventeenth-century stillhouse, and two recent books on distilling women: domestic and commercial.

John Partridge (with his fancy florets) getting all the credit and a Salem housewife getting none!

John Partridge (with his fancy florets) getting all the credit and a Salem housewife getting none!

Gonville and Caius Library, Cambridge University.

Gonville and Caius Library, Cambridge University. British Museum

British Museum

Wellcome Library +Salem Gazette

Wellcome Library +Salem Gazette The medical establishment of Boston, represented by The Boston Medical Journal, responded to Dr. Gregory with an opinion that “the transfer of the responsibilities of the lying-in chamber from the midwife to the educated accoucheur, resulted in a diminution of the mortality incident to childbirth, in the course of half a century, to half the former—and that physicians are more moral than clergymen.” Boston Post, April 4, 1856.

The medical establishment of Boston, represented by The Boston Medical Journal, responded to Dr. Gregory with an opinion that “the transfer of the responsibilities of the lying-in chamber from the midwife to the educated accoucheur, resulted in a diminution of the mortality incident to childbirth, in the course of half a century, to half the former—and that physicians are more moral than clergymen.” Boston Post, April 4, 1856.

Two prints by Moseley Isaac Danforth based on a painting by Charles Robert Leslie, 1837, British Museum and Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts.

Two prints by Moseley Isaac Danforth based on a painting by Charles Robert Leslie, 1837, British Museum and Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts.

Postcards from the 1930s-1950s of the Arbella and what was originally called The Pioneer’s Village at the time, including a very healthy-looking Lady Arbella in front of “her” house.

Postcards from the 1930s-1950s of the Arbella and what was originally called The Pioneer’s Village at the time, including a very healthy-looking Lady Arbella in front of “her” house.

A wonderful view of the PEM’s Ropes Mansion on Essex Street by my friend Matt of

A wonderful view of the PEM’s Ropes Mansion on Essex Street by my friend Matt of

1692 Depositions against Mary Hollingsworth English and Elizabeth Proctor, Beinecke Library at Yale and University of Virginia’s Salem Witch Trial Documentary Archive and Transcription Project.

1692 Depositions against Mary Hollingsworth English and Elizabeth Proctor, Beinecke Library at Yale and University of Virginia’s Salem Witch Trial Documentary Archive and Transcription Project.

A privately printed book of poems by Lydia Very, 1882, Boston Book Company; Ellen Maria Dodge, Salem State University Archives and Special Collections.

A privately printed book of poems by Lydia Very, 1882, Boston Book Company; Ellen Maria Dodge, Salem State University Archives and Special Collections. The Curwen/Bowditch House, Salem, 1890s. Frank Cousins/Urban Landscape Collection at Duke University Library.

The Curwen/Bowditch House, Salem, 1890s. Frank Cousins/Urban Landscape Collection at Duke University Library. Photograph of a Greenwood portrait of Mary Vial Holyoke.

Photograph of a Greenwood portrait of Mary Vial Holyoke.

Harriet Martineau by Salem artist Charles Osgood, c. 1835, Catalog of Portraits in the Essex Institute (1936); and by Richard Evans, c. 1833-34, National Portrait Gallery.

Harriet Martineau by Salem artist Charles Osgood, c. 1835, Catalog of Portraits in the Essex Institute (1936); and by Richard Evans, c. 1833-34, National Portrait Gallery. Salem in the mid-nineteenth century from John Bachelder’s Album of New England Scenery.

Salem in the mid-nineteenth century from John Bachelder’s Album of New England Scenery.

The first Upham work to be reviewed by Harriet, and a sketch of Miss Martineau at work in Fraser’s Magazine, November, 1833.

The first Upham work to be reviewed by Harriet, and a sketch of Miss Martineau at work in Fraser’s Magazine, November, 1833.