For this St. Valentine’s Day I thought I would explore the heart in hand motif, which is probably familiar to most: there are countless items out there with this emblem, produced for or by the Shakers, the Order of the Odd Fellows, heartfelt lovers and/or mourners in the nineteenth century and a whole host of artisans and entrepreneurs more recently. It’s a captivating image, easily accessible and “read”, and highly decorative, but how did it emerge and evolve?

Love Token, c. 1840-60, anonymous American artist, possibly from Connecticut, American Folk Art Museum.

Before the love token, declaring that hand and heart shall never part, or the fraternal staff, denoting “cheerful giving”, there was of course the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the object of intense veneration in medieval Europe. While the spiritual origins of today’s generic and secular symbol seem pretty clear to me, the road between past and present is not precisely a straight path. The image of the Sacred Heart is quite standardized in illuminated medieval manuscripts from the thirteenth century on: a heart, often flaming and always pierced, with attendant Crown of Thorns and the Five Wounds of Christ, wounds which were of course on his hands and feet. But there are evolving variations: the late medieval images below have already made the transition to a more worldly message, encompassing pity, love and charity.

Princeton University Library MS Taylor 17, c. 1500.

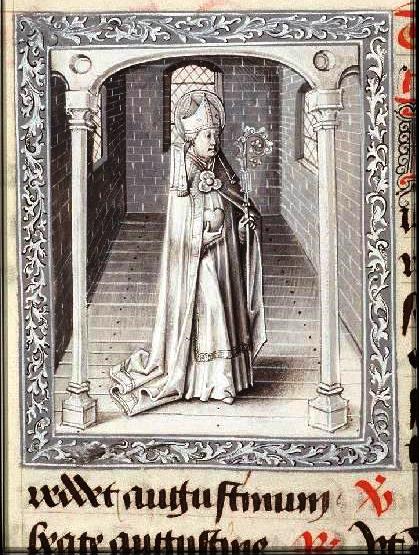

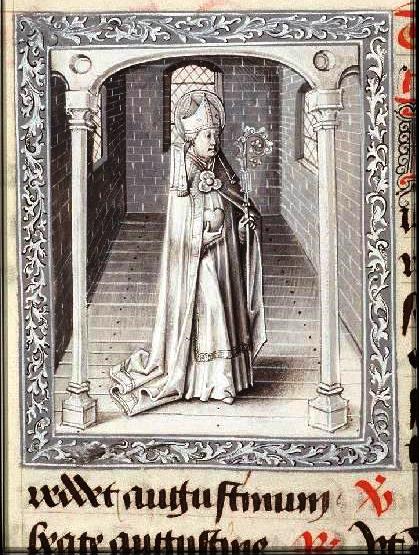

Several of the most important medieval saints, including Augustine, Catherine of Siena and Bernardino of Siena, literally hold hearts in their hands as ever-attendant attributes: Augustine’s restless heart is guided by the Lord, and Catherine actually exchanges hearts with Christ. It seems to me that representations of these two saints humanize the heart somewhat, and late medieval romances contribute to that trend. You begin to see quite average people (well maybe not average, but certainly not saints) with hearts in hand. I suppose that the medieval-clothed Caesar is giving his heart to Rome.

St. Augustine with heart in hand, Nationale Bibliotheek van Nederland MS KB 76 F 2; Giovanni di Paolo, Saint Catherine of Siena Exchanging her Heart with Christ, after 1460, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Arras Tapestry, Offering of a Heart, c. 1400-1410, Louvre Museum; Master of the Vitae Imperatorum, Illumination from Suetonius, Life of Caesar, 1433, Princeton University Library MS Kane 44.

The literal and the spiritual depictions of hearts in hand continue right through the Renaissance into the Reformation, eras of intense lay piety and scholarship. Nothing represents this better than the amazing painting by an anonymous Flemish master of a young man holding a heart-shaped book–he may or may not have been a member of a confraternity devoted to St. Augustine– but this focus on the word anticipates the Reformation, when John Calvin adopted the emblem of a flaming heart resting in a hand outstretched to God for his personal seal. So the Sacred Heart would survive the Reformation, in a way. The influences of classicism and realism affected the motif as well–so we also see hearts in real hands, and in that of Cupid, of course.

Master of the View of Sante Gudule, Young Man Holding a Book, c. 1485, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Carlo Dolci, Study for the figure of “Sincerity”, mid 17th century, British Museum; Francesco Mergolo, Design for a painted ceiling, 1770s, Cooper Hewitt, National Design Museum.

And then we’re off: it’s a straight line from the delftware plate below, commemorating a marriage, to the sentimental tokens of today. The heart in hand motif loses its specific Christian meaning and comes to signify charity, friendship, love, benevolence, sentiment–much more general concepts. The Odd Fellows emblem appears not only on signs and banners, but on a myriad of more mundane items, including tools and flyswatters. Valentine’s Day become a holiday–with all that entails.

Dutch Delftware marriage plate, 1798, Northeast Auctions; Heart in Hand, Independent Order of Odd Fellows, c. 1890 Museum Victoria; 19th century paper love token, Peggy McClard Antiques; “Heart in Your Hand” Gloves by Bonnie Cashin, 1974, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Heart in Hand by Andy Warhol, 1954, Christies “Love” Auction.

Like this:

Like Loading...