Six weeks into the struggle to convince the leadership of the Peabody Essex Museum to return its Phillips Library to Salem, I find myself with lost faith and many learned lessons. The phrase “broken trust” has been applied to the PEM’s actions many times over these past weeks, but that is too legal a concept for me: I prefer to think in terms of faith, encouraged by Victor Hugo’s lovely observation that A library implies an act of faith which generations, still in darkness hid, sign in their night in witness of the dawn. Under the guise of preservation and with a consistent disdain for accessibility and accountability, the PEM leadership broke faith with the community of Salem, and now I have lost faith in them. I’m trying to separate the leadership from everyone else who works at this large Museum, in effect the Museum itself from the policy regarding the Library and its collections, but that’s tough to do when such an all-encompassing feeling as faith is in play. Working on it.

The interior of the East India Marine Hall past and present, and before the installation of the PEM’s newest exhibition, Play Time.

The interior of the East India Marine Hall past and present, and before the installation of the PEM’s newest exhibition, Play Time.

I’ve learned many lessons over these past weeks but I think the most important one is about prejudging in general and my own prejudices in particular. I’ve been concerned about the commodification of history in Salem for quite some time (as regular readers are all too aware!) and assumed that this trend was driven exclusively by the many tour guides in town, who were presumably more concerned with #tourismmatters than heritage. Now I know that that predisposition is largely incorrect, as I have seen and heard tour guides take earnest and public stances in support of the return of the Phillips while established heritage institutions have stood silently on the sidelines, taking no position and choosing not to exercise their more considerable influence. I remain impressed, and heartened, by the power of history to unite a broad spectrum of people, although at the same time I realize that history, or the perception of one’s history, is also intensely personal.

The Collections of the Essex Institute in the Phillips Library Reading Room, 1980, and the library collections reinstalled, 2008, Rizvi Architects.

The Collections of the Essex Institute in the Phillips Library Reading Room, 1980, and the library collections reinstalled, 2008, Rizvi Architects.

I’ve been having difficulty separating the personal from the professional in my reaction to the PEM’s policy towards the Phillips ever since the “announcement” was made—actually I don’t even think I can get past the “announcement”, or lack thereof! But I better try, because obviously no apologies will be forthcoming; instead PEM CEO Dan Monroe offered only the assertion that there was an expectation by a number of people that we had a responsibility to consult with them about what would be done with the Phillips collection…an expectation we didn’t particularly share or understand in last week’s Boston Globe article. I certainly wasn’t expecting a consultation, but an announcement might have been nice, especially as the PEM’s last official word on the Phillips was that it would be returning to Salem in……..2013.

Thank goodness, when confronted with such adversity, healthy instincts of self-preservation begin to take over, and so I’ve started to privilege the professional over the personal in my considerations. When I look at the situation from the former perspective it is clear to me that I don’t need the Phillips Library in Salem or even in Rowley. I have a car, a Ph.D., and a flexible schedule so I can probably gain access to the new warehouse library during one of the 12 hours a week or so that it will be open (well maybe not, after my running commentary over these past weeks) if I want to. In any case, I’m an English historian, fortunate to be equipped with academic databases and dependant on repositories that have made the accessibility of their collections a priority. Local history is just a lark for me, right? Unfortunately, private priorities only work for a while: when I start thinking about all those records relating to Salem people, places and institutions, and all those Salem donors, I find myself right back in the realm of public history.

Actually, I do have three presentations coming up this year on the intersection of the Colonial Revival and historic preservation movements here in Salem—all of which were scheduled just before the temporary Phillips facility closed down on September 1, ostensibly so that materials could be readied for the big move to Rowley (which was not, of course, announced at that time). I was looking forward to using the library’s collections intensively for the first time in my career, an opportunity that will sadly not come to pass. I’ll have to make do, and I will make do, with the help of other institutions that have made their materials more accessible and lots of secondary sources, but I fear I will only be scratching the surface of this Salem story without the Phillips sources.

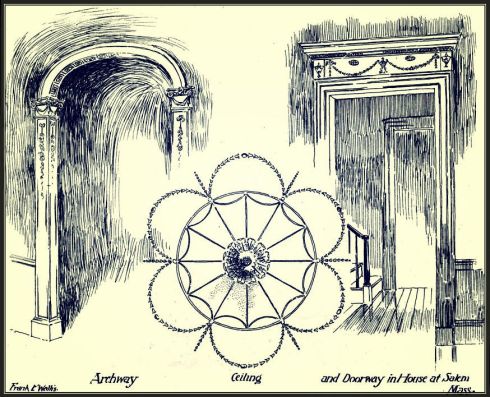

And I really fear I’ll be too reliant on the detailed-yet-romantic work of Maine-born architect Frank E. Wallis, whose reverence for Salem is all too apparent! Plates from Frank E. Wallis, Old Colonial Architecture and Furniture. Boston: George H. Polley & Co. Publishers, 1887.

And I really fear I’ll be too reliant on the detailed-yet-romantic work of Maine-born architect Frank E. Wallis, whose reverence for Salem is all too apparent! Plates from Frank E. Wallis, Old Colonial Architecture and Furniture. Boston: George H. Polley & Co. Publishers, 1887.

January 21st, 2018 at 5:47 pm

Donna, I completely understand your sadness and anger over this situation with the planned removal of the Phillips Library Collection from the Peabody storage facility in April to the new storage facility in Rowley vs. back to Salem.

If all the forces currently in play to prevent this move are to fail, what would you consider to be a reasonable mitigation to be paid by the PEM to the citizens of Salem and all the patrons of the Library?

Would a dedicated budget of a significant amount to be earmarked and guaranteed for digitization of the collection—to be started immediately upon installation of the collection in Rowley—begin to help show some respect for the sacrifice of Salem citizens and all who treasure and use the collection?

Would there be other elements of mitigation that you would consider appropriate and necessary?

January 22nd, 2018 at 8:19 am

Hi Jessica—I am concerned that the PEM’s offer to keep the reading room open is merely a repackaging of their original statement (well, after the “announcement”) that it would become an exhibition library. Given that the PEM’s exhibitions are very seldom on local or regional subjects—except perhaps in a very broad thematic way—this would still result in severing Salem from its historical archives. As Mr. Monroe has stated several times, he could see the Essex Institute Historical Collections (well, he doesn’t seem to know the title, but I think that’s what he meant) in there but that’s about it. That’s not helpful, as the Collection are just down the road, in the Salem Room of the Salem Public Library. That said, I suppose the best mitigation would be terminals with access to digitized materials but they are so very behind in the process of digitization—and they don’t even appear to have a PLAN–that that really concerns me too.

January 22nd, 2018 at 1:51 pm

Hi Donna, I am working on a couple of things now and will share as I have the details figured out. Time is short, but I am by no means deterred…quite the opposite…I love a challenge, especially one that looks impossible…..the Working Group’s kick off meeting date is yet to be set, but it looks like it may be Wednesday, January 31st. I will have many things prepared to be presented, and look forward to your input. R/Jessica

January 23rd, 2018 at 5:37 pm

“Us-and-them-ness”, “nostalgia-ness”, and Alternative Paradigms

John Grimes

I have kindly been invited, by Dr. Seger, to participate in this blog, and to continue to provide my own perspectives on the Peabody Essex Museum, including its decision to create a centralized, off-site preservation facility for its collections, including that of the Phillips Library. If you know me, or have read any of the other comments that I have recently posted online, then you know that I worked for PEM (no longer, and I do not now speak for PEM in any capacity) for some three decades, as a curator, collections manager, and a deputy director, before, during and after the consolidation of the Peabody Museum of Salem (where I started) and the Essex Institute. I have a deep familiarity with the combined collections, and have used the Phillips Library extensively over the years, as a curator and collections manager.

I’ll be upfront, as I have been elsewhere, that I think that PEM is making the correct decision to create this comprehensive off-site facility for its collections. I’ll also foreground my belief that the accessibility the of the collections is of paramount importance, and I am entirely of the opinion that this can be achieved in various ways, including digitization, scheduled access, remote retrieval to Salem, etc. Many of the reasons for my opinions in these areas have been posted elsewhere, and I won’t reiterate them here except as they might become relevant in subsequent posts. Here, instead, I would like to explore other issues. Before I do, I want to say how much I deeply appreciate the opportunity to post here, especially so when other venues have sometimes become so vitriolic.

Putting aside any response to the vitriol, which merits no response, and setting aside, at last for the moment, logistical issues of preservation and access, there are at a few themes that I have detected in the social media discussions, that I think can be constructively highlighted and discussed.

First, I would point at an “us-and-them-ness” underlying at least some of the discussions, with the “us-ness” variously alluding to local residents, local history, local objects, and local perspectives and needs, and the “them-ness’ taking the form, more or less, of outsiders, other kinds of objects (especially art), outside perspectives and needs, other cultures. Second, I would point to a “nostalgia-ness” theme, a longing for the old Peabody Museum of Salem and/or the old Essex Institute, a longing for the way they used to be, and the ways that they presented their collections, before the advent of PEM.

Lest the reader conclude that I am being at all condescending, or that I am vilifying in any way any of the polarities I have presented, I am not. Rather, I but put them forward because they are precisely the polarities that confronted us internally when trying to develop a new organizational paradigm for PEM. The collections of both the PMS and EI were in fact each many different collections, brought together over time by evolving collecting priorities by the consolidation of collections from seven predecessor organizations, each collection infused with the motivations of the people and organizations that collected them. These motivations usually included, in large measure, the polarities of “us-and-them-ness” and “nostalgia-ness” that I’ve described. The major challenge of developing a new unifying paradigm for PEM was in the distillation of a more meaningful “the-whole-is-more-than-the-sum-of-the-parts-ness” from the huge and almost overwhelmingly-diverse entirety.

In seeking this distillation, we (and I can only speak to the “we” from my own perspective) had to become keenly aware of traditional contexts within which museums operated, and the standard museological paradigms, which we more limiting than helpful, entirely inadequate and frankly obsolete for the purposes sense-making of the collections, or for developing an epistemological compass that would help visitors find meaning that transcended “us-and-them-ness” and “nostalgia-ness”.

I can do no better here, in describing some of the limitations of traditional museum paradigms than to quote excerpts from an earlier essay of mine, “A PERSPECTIVE ON THE NATIVE AMERICAN COLLECTION OF THE PEABODY ESSEX MUSEUM” included in Uncommon Legacies: Native American Art from the Peabody Essex Museum (American Federation of Arts, in association with the University of Washington Press, 2002. I include this not to feed my ego, but because it was and is my best effort to explain some of the issues at the heart of any effort to move beyond simple “us-and-them-ness” and “nostalgia-ness” in museums.

_______________

First housed in a rented hall, the [East India Marine] Society’s collection rapidly grew from the donations of members. Later, as the museum’s fame spread, gifts came from individuals not connected to the Society, sometimes deposited with Salem-bound captains met at sea. An 1805 letter to the Salem Gazette gives a sense of the rapidly growing reputation of the museum, noting,

“the Society’s collection of rare and valuable curiosities surpasses any in New England; and the large additions which are daily made to it induce us to think that it will soon be the first in the United States… Your descendants, in some distant day, will look at what you have done, and while they admire and reverence the indefatigable industry and bold enterprise of their fathers, will feel stimulated to like exertions.”

The scope and size of the collections have grown far beyond what the founders could have imagined. They are widely renowned today for their high quality and early provenance, especially in the fields of American decorative art, architecture, maritime history, Asian art, Oceanic art, Native American art, and African art, as well as photography and rare books and manuscripts. Despite the changes and growth, the Society’s collections remain the starting point for any consideration of their meaning and significance; they are the core of the Peabody Essex Museum’s present-day Native American collection and give it the distinction of being among the oldest ongoing collections of Native American art in the country, and perhaps in the hemisphere.

During the latter part of the nineteenth century, equipped with a new vision (and a substantial gift from philanthropist George Peabody), the museum focused on scientific purposes, and its curators busied themselves systematizing the collections and acquiring missing “type” specimens, usually through exchange with other museums. By about 1900, and for most of the ensuing century, a different set of motivations prevailed. and the collections were directly and indirectly employed in the portrayal of Salem’s history and maritime heritage. Thus, the Native American collection, like the museum as a whole, has undergone several periods of significant change, each following its own paradigmatic compass. Today [2002], the museum is engaged in reinventing itself once more, taking stock of its two centuries of experience, in order to meet the challenges and opportunities of a new age.

During its history, the museum has attracted the involvement of many scholars, donors, and patrons, all successors to the spirit of inquiry of the Society’s founders. These individual personalities have played important roles, adding unique qualities to the museum as each new generation has assumed stewardship. Past directors such as Frederick Ward Putnam and Edward Sylvester Morse were innovators of national and international stature, significantly influencing nineteenth— century museology. However, even with the imprint of such individuals, and the modulations of shifting societal zeitgeist, the museum’s essential underpinnings have remained remarkably constant across time, anchored to an identifiable cognitive and philosophical foundation. An understanding of this grounding is essential to any discussion of meaning and aesthetics in museum collections, particularly with respect to non—Western art…

The two fundamental elements of the museum’s intellectual structure were identified in its 1799 charter: curiosity and cabinet. Curiosity, in the eighteenth century, referred to an object of wondrous quality, meriting appreciation and study, as opposed to the contemporary connotation of the odd or strange. In its earlier meaning, curiosity comes closer to our modern (positive) description of personal inquisitiveness. Curiosity is a basic human quality. It has been described as a hunger for knowledge, the pursuit of the unknown for the intellectual and emotional pleasure that arises from integrative thinking. The focus of curiosity is the boundary between the familiar and the unfamiliar, a frontier delineated by fundamental human cultural and cognitive processes. Culture is a major influence in defining the landscape of the familiar. Cultural behaviors merge with and animate the environment, predisposing individual minds toward a normative cognitive map. As the pathways of this map are externalized through behaviors, the cycle begins again.

A cabinet, as understood by the Society’s founders, was a tool for displaying and organizing knowledge, part of a tradition traceable to the sixteenth and seventeenth—century Wunderkammer (cabinet of curiosity) established by European aristocracy. Ranging in size from small displays to entire rooms, such cabinets were repositories for objects of rarity and variety, capturing “the plenitude of the world represented in… microcosm.” The overt purpose of these assemblages may have been as scholarly reference, or as a display of personal wealth and worldliness. However, we can also see in their proliferation a powerful new

medium for bestowing meaning and status on objects.

In a real sense, cabinets represented a projection of the collector’s intellect, an externalization of personal memories, values, and relational hierarchies.

Two developments in the eighteenth century are especially pertinent to the history and the development of cabinets and their successors, museums. The first development, beginning in the mid—eighteenth century, was the transformation of many private cabinets into public museums, notably the British Museum and the Louvre.

The second development, an outgrowth of the first, was the evolution of museums away from their status as personal intellectual artifacts. Instead, they became didactic environments for conveying national and social narrative. In the context of eighteenth-century Europe, the theme of this narrative was a hybridization of two elements: Enlightenment idealism based on the expectation of human improvement through reasoned thinking; and imperialism, arising from an acceptance of European dominion as the natural order. Through a combination of these factors, museums became a means of communicating Eurocentric ideals. They became “representation machines” that sorted objects, places, and people along axes of distance (familiar-exotic), difference (us-other), and quality (refined—crude) according to European standards. Thus curiosity and cabinet came to serve ends that were ultimately ideological.

Despite these and other updates, such as the accommodation of Darwinism and new museological practice, the intellectual pedestal on which museums rest has changed little in two hundred years. The nineteenth-century differentiation of museums into the now—usual categories of art, history, and natural history/science did not force any significant alteration of the underlying canon. Since the 1860s, for example, the Peabody Essex Museum has straddled all of these categories, displaying its Native American collections at various times as historical, archaeological, ethnological, and, most recently, art objects. The easy transportability of collections between categories hints at one of the

underlying flaws of Modernism, as “practiced” not just in Salem, but everywhere: whatever the outward form of presentation, there is only one real story at the core, a “grand narrative” whose underlying values and logic are essentially Eurocentric.

Small wonder, given this, that the arts of Africa, Oceania, and Native America were invisible to nineteenth—century art discourse, or that, through much of the twentieth century, museums and academics relegated such ”primitive” traditions to the background of avante-garde exploration of elemental (”savage”) society and expression.The fact that such works now appear more frequently in art museums falls well short of rectifying our long- distorted value systems; on the whole, we are still too comfortable encountering non—Western artworks in natural history displays.

In recent decades, Modernism has become unsustainable as an intellectual framework. Doomed by the demise of colonialism and the rise of economic globalization, feminism, and minority empowerment, the “grand narrative” has yielded the floor to the voices of local history, culture, and values.

[In a later post, I wish to pick up on this thought, and what it means locally for PEM. This post, by the end, will be too long already, leading some to conclude, as others have, that I am simply long-winded.]

Dissolution of their two—centuries-old Enlightenment/Modernist substrate presents museums with a series of significant dilemmas. In the absence of a narrative arrow, what is the point of museum didactics? What moral charter entitles them to house and collect works of art? What object-based experiences do museums provide their visitors, and how is the success of this encounter to be judged? This is not just a problem for the presentation of Native American and non-Western art but an issue relevant to the contemporary role of all cultural institutions in a plural world. As we cross the threshold of a new millennium, museums require new and sustainable paradigms that truly abandon the vestiges of colonialism. In this new era, museums should strive to surpass Postmodern deconstructivism. Unification through humanistic discourse is possible. Any new paradigm will need to be a broadly rooted tree that draws sustenance from multiple belief systems to support a common dialogic canopy. Rather than acting as a single narrative voice, national and global museums in the new century should facilitate interactive meetings of diverse speakers. Museums can become anthologies of essays rather than encyclopedias for a singular worldview. Such anthologies will require the concordance of shared transcultural vocabularies for discussing objects, their qualities, and their aesthetic effect. For the Peabody Essex Museum, the new paradigm remains planted in curiosity, as was that of the Society captains, but this time it is curiosity that seeks freedom from ideological boundaries. The new paradigm opens the locked doors of the cabinet, allowing us to move beyond possessive knowledge of objects and admitting new relational knowledge and aesthetic experience.

January 23rd, 2018 at 10:19 pm

I appreciate your perspective, and your history, John. I do see the fruits of the successful struggle (it seems almost like a struggle in your discourse, but maybe it was more of a process) to meld the two institutions into one which had a new identity and represented a new paradigm. I do not enjoy criticizing the PEM; you see my own struggle here.

January 23rd, 2018 at 11:15 pm

It was certainly a struggle. Process would have landed us back in the traditional approaches, which would have failed, I believe.

January 24th, 2018 at 9:44 am

I don’t disagree. My own particular interest in the Colonial Revival evidenced in this post is my own particular interest, fueled by my study of the Renaissance, which was a culture that looked back to move forward. But I certainly don’t think the PEM should have chosen that “nostalgic” path forward. On the other hand, I do note a very old-fashioned view of historical interpretation in the PEM’s messaging: with an exclusive emphasis on the failures of living history museums and no appreciation for the current historiography in any of the fields tied to its collections’ subject strengths.

January 25th, 2018 at 5:10 pm

Exorcising the Genie

John Grimes

I am continuing from my previous post with the goal exploring, from my own point of view, what it means to “put” local history into, or back into, PEM, which is clearly one of the themes present in the discussion about off-site storage. To do this, I need to pick up from my last post, which related my own experience attempting to navigate beyond the traditional museological constraints in search of a different guiding philosophy and interpretive compass for museums. The context was the development of an exhibit (which opened at Stanford University’s Cantor Art Center in 2002, and at PEM in 2003) of early-collected Native American objects in the PEM collection.

Up to that time, in the field of Native American art, curators had generally “situated” objects within one or more of the following frameworks: as “art”, as defined by, and “squeezed” into, western notions of art (sometimes with a gloss of Indigenous-language nomenclature); as anthropological phenomena (or worse, in the day, as “specimens”), exemplars of material culture within culture-areas (more or less externally-defined); as historical objects in support of an external cultural narrative, rarely as part of an Indigenous narrative (e.g. a Penobscot basket, in the context of the history of the Penobscot Nation, curated by a Penobscot scholar). I was uncomfortable with these approaches, especially as, along with the rest of PEM’s leadership, we were trying to develop new paradigm.

My discomfort with these traditional approaches was with what I alluded to earlier, i.e. that whatever outward form they take, all these frameworks are inevitably anchored the the same substrate, one implicit narrative, whose values and logic are virtually irredeemably Eurocentric, androcentric, rooted in lingering Enlightenment rationalism, in post-industrial, post-WWII notions of “progress” (and conversely, notions of the “pre-progress” past, or the contemporary state of the “developing” world), and capitalist value-systems, etc.

As soon as this narrative genie – in any of its guises – is invoked, the museum environment is transformed into a place of voyeurism (“us” looking on at “their stuff”) and melancholic or nostalgic in-substantiation (“us-and-them-ness”, but with the added ingredient of “fading”, the implication of diminishment brought about by time, “primitiveness”, connotations of disappearance, loss, and death), and commercialization (museums are incontestably part of the system of valuing/devaluing objects, artists, historical and contemporary people, etc.). Museums, as a whole, have such a long history as purveyors of voyeurism, in-substantiation, and commercialism, their combined residual impact still affects their visitors, despite any museological reforms one might cite, because visitors’ inherited preconceptions of what they will experience, colors, at least subliminally, what they actually experience.

How did I exorcise the narrative genie from the 2002 exhibition? Truthfully, I was only partially successful. Multiple voices were represented in the exhibition and catalog, and the latter, especially, attempted to position the objects as “sovereign” in their own right, to be respectfully approached without imposed reference to an external and imposed narrative. I also tried to recalibrate how the word “art” was used in the exhibit and catalog, i.e. as creative expressions/utterances of people we could not know, but who still lived present in their utterances, and who stood with us now, on the verge of humane dialogue (Martin Buber’s I and Thou provided this transformation insight).

Even if I did not completely solve the problem that I wanted to solve, I was content to have made headway in the elucidation of PEMs new paradigm as an “art and culture” museum. I had one other chance to explore “the frontiers” of the art-and-culture paradigm (an exhibition of Canadian Inuit art/creativity) before I left to become the director of the IAIA museum in Santa Fe, and was please to make what I thought were inroads into what the new paradigm meant. From a distance, now as a spectator, I have seen PEM continue to explore the implications of its paradigm, and I think that overall, they’ve been quite successful, and that their continued organizational growth, support, and increasing attendance are evidence of this.

I love museums, but I do strongly believe that they need to radically transform themselves from what they have been in the past, to be part of a humane pluralistic discourse moving forward, or even to be sustainable (museum attendance is in decline overall, due to an ongoing decline in the attention people are willing to give them, being diverted to all the many other kinds of virtual experiences available online). I think radical transformation for PEM means continuing to explore the implications and possibilities of their art and culture paradigm, including, as for all museums, giving constant attention to ways of exorcising the time-worn, toxic genie(s) of voyeurism, in-substantiation, and commercialism, as I have described above.

What does all this mean, with respect to the calls for PEM to “put”, or “put back” local history into what they do? I will save my ruminations on this for my next post, but I will say here that whatever they might do, as they continue to explore and develop their paradigm, should, in my opinion, not look, or be expected to look, like what PEM’s processors did formerly.

January 25th, 2018 at 5:27 pm

I was really hoping that you would comment on my most recent post on the pem #digitizationfail. No luck, I guess! Ok well I’ll come back later re: commercialism.