I don’t usually subscribe to those specially-designated days–you know, Boston Cream Pie Day or Talk Like a Pirate Day–preferring the old saints’ days of yore with all of their associated traditions and folklore, but I am acknowledging National Handwriting Day today simply because I like the written word almost as much as I like the printed one, and scripts almost as much as fonts. And I fear penmanship might be on its way out. This Day was established by an entity with a vested interest, the Writing Instrument Manufacturers Association, all the more reason to ignore it, but they chose John Hancock’s birthday as the day and I welcome any occasion to acknowledge Mr.Hancock, one of my favorite founding fathers. I learned a lot about penmanship pedagogy a few years ago when I fell in love with a calligraphic cat and plunged myself into the world of nineteenth-century American writing manuals, but now I think the seventeenth century is a more important era in the development of writing instruction, at least in England. Influenced and inspired by continental influences like Jan van den Velde’s 1605 book, Spieghel der Schrifkonste (Mirror of the Art of Writing), English writing became penmanship, separated from “orthography” or grammar, segregated into a variety of hands and scripts, standardized through the dissemination of a succession of manuals and “copy books”. All those Victorian flourishes and calligraphic creations? Old news.

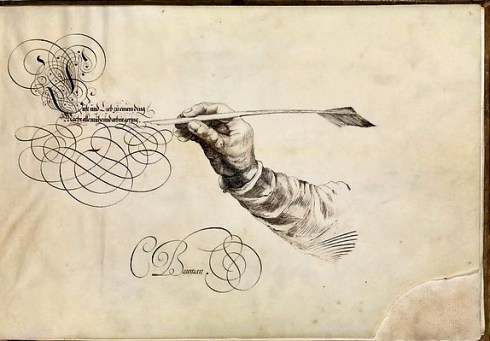

Above: writing samples from the early seventeenth century: a 1620 pen-in-hand engraving after Jan van den Velde, c. 1620, Metropolitan Museum of Art; a page from van den Velde’s influential Mirror of the Art of Writing, c. 1605; and title page of Martin Billingsley’s The Pen’s Excellencie, or The Secretaries Delight (1618).

Below: in the later seventeenth century, it was all about “Colonel” John Ayres, master of a writing school in St. Paul’s Churchyard “at the sign of the hand and pen” in London, and the author of a series of copy books published in many editions between 1680 and 1700, including The Accomplish’d Clerk or Accurate Pen-man and The New A-La-Mode Secretarie or Practical Pen-Man (both 1682-83).

January 23rd, 2016 at 1:30 pm

That’s lovely, actually. I love revisiting those old letters with their now-sepia ink, written so often poetically and in that fine hand. Perhaps a ‘lost art’ to bring back around. 🙂

January 23rd, 2016 at 1:32 pm

I agree. I actually know a few people who really cultivate the art of writing since its seems semi-endangered. Stationary is still very big–who knows?

January 23rd, 2016 at 1:40 pm

Beautiful.

January 23rd, 2016 at 2:37 pm

I’m sure you’re familiar with Handwriting in America: A Cultural History, by Tamara Plakins Thornton. It’s a wonderfully informative book and I would encourage anyone with an interest in any aspect of handwriting to read it. I was especially interested in the concept of differing “hands” for persons of different genders, occupations, status, etc.

January 23rd, 2016 at 2:47 pm

You know I think I picked it up once, but I have yet to read it, Priscilla–thanks for the reminder.

January 23rd, 2016 at 7:42 pm

This is rather secondarily related, but…I was aware, of course, that spelling was not necessarily standardized even among the educated in the 18th century. But I loved transcribing letters where the spelling was completely phonetic. I had to read them out loud to transcribe them, their spelling was so off, even by their time period’s standards. And these people had not been trained in handwriting, or in polite letter-writing either. When I read Jill Lepore’s biography of Jane Franklin, it was as if she were talking–Jane Franklin–in my head–precisely because, unlike her brother, she’d had no training in all those things that can turn a letter into “literature” of sorts that one reads. Instead Jane Franklin was “talking” in her letters. It was so interesting…

January 23rd, 2016 at 8:09 pm

Great point, Laura. It took me so long to read 16th century script for my dissertation–I was interested in these 17th century instructional texts precisely because they began the process of standardization…..but it took a while.

January 24th, 2016 at 8:26 pm

It was over a decade ago I had a student for the first time who could not write in cursive, only print letter by letter. He literally couldn’t write an essay fast enough in exams.